Walker to Climber - Here's How

If you've ventured into the winter hills more than once or twice, you'll have seen winter climbers: men and women with short, bent-shaft ice axes strapped to their packs, marching at speed up to the North Face of Ben Nevis or into the Northern Corries. Are they mad? Perhaps – but if you're winter climbing curious too, here's a primer for the winter walker who dreams of more vertical challenges.

Before we begin, it's worth pausing to reflect on the possible dangers. The BMC sum it up well with their Participation Statement:

The BMC recognises that climbing and mountaineering are activities with a danger of personal injury or death. Participants in these activities should be aware of and accept these risks and be responsible for their own actions.

The Scottish winter scene is one of the biggest rewards out there. A fine line between a complete sufferfest and a complete joy. It's a love/hate relationship that I wouldn't change for anything

Meet the professionals

Jamie Bankhead was a founding team member of the Ice Factor climbing centre in Kinlochleven, and now works as a freelance mountaineering instructor based on the Isle of Skye Jamie Bankhead Mountaineering

Di Gilbert works full-time as an independent mountaineering instructor based in the Cairngorms National Park. She has never had a 'proper job' and says this is unlikely to change now! Di Gilbert Mountaineering

Samantha Leary is a full-time professional mountaineering instructor with over 30 years of experience. She lives in Scotland for the winter and Wales for the summer Leading Edge Mountaineering

What is winter climbing?

In the British winter hills, the grey area between hillwalking, mountaineering and climbing is so broad that many walkers will have ventured onto 'climbing' terrain without even knowing it.

Di Gilbert sums it up well:

"If you are a keen hillwalker who climbs Munros in winter conditions, there is a good chance that you are already a winter mountaineer. There are many classic routes that require a bit more knowledge, and perhaps more equipment, than conventional hillwalking skills."

"Making the transition to winter climbing is much clearer when you purposely head out with an aim of venturing into steeper and more technical terrain – and you will certainly be packing differently."

To keep things simple, we'll say that any route given a winter grade in a guidebook – or equivalent unrecorded terrain – qualifies as climbing. The easiest beginner routes are graded I, II, or sometimes I/II.

A good example - albeit a big step up for most walkers - is Ledge Route on Ben Nevis. Graded II in winter, this is the classic easier ridge route on the forbidding north side of Ben Nevis – mostly straightforward general mountaineering terrain, but highly exposed, highly consequential should you slip, and with sections that may require a rope. Like many winter routes of its type, it's a classic scramble in summer. Examples of popular easier hillwalkers' winter mountaineering routes at a more amenable grade I include Striding Edge, the CMD Arete and the Snowdon Horseshoe.

How much experience do I need?

There is no one correct path to becoming a winter climber, but at a minimum you'll need to be a competent winter walker with a decent grounding in the fundamental skills:

- Navigation

- Safe movement on snow and ice

- Ice axe and crampon use

- Avalanche awareness and avoidance

- General winter hillcraft

It's also useful to have some summer climbing or scrambling experience, as many of the basic rope skills are transferrable. If you don't know your karabiners from your Camalots, it's a good idea to acquire a little summer climbing experience before diving in at the deep end in winter.

"To operate confidently on Grade I/II ridges and gullies the aspirant mountaineer should have a solid volume of experience on hillwalking ground," Jamie Bankhead says, "to the extent that their movement and composure is steady and reliable even on run-out and highly consequential terrain."

"This is the first prerequisite and really can't be short-cutted – mountaineering routes that cover a lot of ground (the Ring of Steall, for example, or the Snowdon Horseshoe) will often require large sections to be climbed unroped if they are to be completed within daylight."

You'll also need to be fit. A winter pack is already heavy, but add to that a second ice axe, rope, harness, and other hardware, and winter climbing loads can really sap the stamina reserves... and that's before you add the extra physical demands of snow-covered ground and wild weather.

Here's Samantha Leary's take:

"If you're out and about in winter and regularly manage mountain journeys of around 6-8 hours (wearing crampons for around half that time), if you can navigate in poor visibility, and are able to plan this sort of day taking into account weather, conditions, terrain, and the abilities of you and your party, then venturing onto more complex and steeper routes could be possible for you."

Skills

Read the UKHillwalking Winter Essentials for Beginners guide to skills and dangers here

Where to learn the necessary skills

1. The DIY approach

It can be tempting - and satisfying - to learn as you go with a mate, but it isn't always the safest approach. You run the risk of forming bad habits without having the chance to learn safe practice from someone wiser than yourself. At the very least, make sure you team up with someone who has solid relevant experience, and keep your ambitions modest to begin with.

"The scenario of peers 'learning on the job' together is often quite scary to watch," Jamie Bankhead warns, "particularly when techniques that may have been observed being used in a different context are aped. The classic case study here is 'moving together', sometimes referred to as 'short-roping'. Done well this can be a very efficient form of moving through certain terrain, but when misapplied it can see a whole team tied together on an open slope, where a slip from one will almost certainly deposit everyone at the boulders below."

2. Join a climbing club

There are many climbing clubs throughout the UK, and joining one can be a good way of finding your feet. Some help organise winter skills courses and of course being a club member is fantastic for networking with more experienced climbers. However, beginners could still benefit from formal instruction.

"Clubs are a great way to meet climbing partners but there is no substitute for learning from people who spend many hours refining their technique," Di Gilbert says.

3. Get professional instruction

Di Gilbert says: "The biggest thing about transitioning from hillwalker/mountaineer to climber is to learn from the professionals – no point having all the gear but not the faintest clue how to use it."

"The minimal qualification for winter climbing instruction is somebody who holds the Mountaineering Instructor Certificate (MIC) or a British Mountain Guide. A good place to find these people is through their websites: mountain-training.org and bmg.org."

Mountaineering Scotland also have a good article about hiring a guide - see here.

- Don't forget UKH's instructor/guide directory

Movement skills

In addition to the basic techniques for moving safely on snow and ice, you'll need to learn how to climb steeper ground. To state the obvious, perhaps, winter climbing demands more mastery of axes and crampons than walking.

A single axe can be used on easier winter climbs, especially grade I and II ridge traverses; but it will need to be a shorter and more technical axe than you might own for walking. On gullies, or more sustained mixed ridges and buttresses, a pair of short climbing axes is the choice favoured by most people. Movement with twin axes requires the front-pointing technique – standing on the forward-projecting points of your crampons and allowing your feet to take your weight while your ice axes provide balance. In the lower grades, most of the time you won't be hauling yourself up by your axes. On rocky mixed ground or ice, axes are swung by the handle; on steep snow you've a choice (depending on the angle and the consistency) - either plunge the axe shafts into the snow, 'dagger' with the picks, or swing them as for ice.

Since front pointing all day up easier angled ground is tiring and inefficient, other crampon techniques need to be perfected too. And all of this needs to become second nature, which takes time and practise.

Conditions and ethics

- Read the UKHillwalking Winter Essentials for Beginners guide to weather and conditions here

Conditions underfoot can make a huge difference to your experience on the climb. While climbers continue to debate just what constitutes acceptable conditions, at a minimum, a climb is said to be 'in condition' or 'in nick' when the route looks wintry (i.e. white). Also:

- For mixed or rocky routes, turf must be frozen and rock must usually be frosted or snowed up.

- Gullies should contain enough snow and ice to cover any rock features such as chockstones that are usually buried in winter.

- Routes should be safe from avalanches – that includes the approach and the return trip home. An easy gully can become a death trap in certain conditions.

- Ice routes should be frozen and contain sufficient ice.

Climbers learn how to build a picture of how conditions are developing by studying weather and avalanche reports, plus keeping up to date with the blogs and social media of other climbers. The forums on UKC and UKH are helpful too, as is the winter conditions page, which lists recently logged climbs (best used in conjunction with other sources, as there's no way of knowing for sure if a logged route was in condition when climbed). Avalanche and weather forecasts are as useful for climbers as they are for hillwalkers – if not more so.

"Thanks to resources like the SAIS (Scottish Avalanche Information Service) mobile app and Be Avalanche Aware process," Jamie Bankhead says, "knowledge about snow and weather analysis, and the critical decisions that must be made regarding avalanche hazard, are becoming easier to acquire."

"There's no point being a great mover and a ropework magician if you invite a snow burial," Jamie adds, "and in Scotland these tend to kill. The lure of the classic gully line must be played off against the inconvenient truth that on some days these are absolutely the worst places to be. On those days, ridges are your friend."

Ropework and belaying

- Read the UKC guide to protecting winter belays here

A comprehensive guide to winter ropework is well beyond the scope of this piece, but it's often best to keep things simple when starting out on easy routes: learn basic and reliable techniques that can be applied to a wide range of situations with a minimum of extra gear.

You'll rarely find steep ice on Grade I routes, which largely consist of relatively easy terrain plus one or two much shorter sections, or 'steps', that are more difficult. These steps could include steeper snow slopes, snowed-up rocky scrambling, or the occasional step of easy-angled ice.

It's important to learn ropework skills in a controlled and safe environment before jumping in at the deep end on a winter crag. Get some instruction, preferably in summer to begin with. At a minimum, you should know how to:

- Belay a climbing partner.

- Look for and find suitable anchors. On easy routes, most anchors will consist of spikes that can be protected by a sling, rock cracks, or winter-specific options such as a snow bollard or buried ice axe. Hammered pitons can still be useful in certain situations but should be used with discretion as they can damage the rock or become fixed in place. Ice screws are rarely necessary on easy routes.

- Construct a belay using either rock protection or snow anchors.

- Protect a pitch with runners.

- Escape from tricky ground by abseiling.

What about once you've mastered the basic skills and are looking to improve your efficiency? At this point you'll be experienced enough to know when it's appropriate to take the rope out and when you can safely leave it in your pack.

"On routes at the lower end of the spectrum, a simplistic approach can still be used," Jamie Bankhead says. "If one is familiar with snow anchors and belaying from them, and can master the direct belay from a rock spike or thread, it may be that a rope, sling and a few karabiners will solve all obstacles."

If in doubt, all else being equal, it's safer to rope up than to solo easy ground until you're more experienced. Develop your skills on relatively short routes before taking on something long such as the Aonach Eagach where you'll need to solo easier sections to avoid getting caught out by approaching darkness. 'Moving together' is a technique that can offer the best of both worlds for the experienced, but can be dangerous if misused. As a beginner, it's best avoided.

"Staying tied on when climbing easy ground is going to be sketchy if moving together," Jamie adds. "It's often pointed out that Guides and Instructors do this, but it takes them a lot of training and experience to get to that point, and all that I know have a pronounced appreciation of where it does and doesn't work."

Gear

- Read the UKHillwalking Winter Essentials for Beginners guide to clothing and equipment here

Di Gilbert says, "On top of all your winter hillwalking equipment, you'll need some specialised items of climbing gear. If you are a summer climber, many of your items can carry over to winter."

A climbing rope is rarely useful alone – you need extra hardware for building belays to anchor you to the mountain, not to mention intermediate 'runners' for protecting a pitch. Most climbers will prefer a smaller, focused selection of gear on an easy winter route – but experience is critical.

"If you don't have the knowledge of where it's appropriate to apply a minimal-kit approach," Jamie Bankhead says, "I'd argue for acquiring it in a summer context (scrambling or rock climbing) then transposing it to winter. On the average summer day you'll place more gear and be in a less hostile learning environment."

- Read the UKC guide to winterising your rack here

Di Gilbert's list of essentials:

- Helmet – Your summer climbing helmet should suffice.

- Harness – If your summer harness will fit over all the extra layers, this should also do. I prefer a minimal padded and fully adjustable harness with big gear loops.

- Rope – A full-weight 50m rope as a minimum. If you're familiar with double ropes, these are a very good option for more challenging winter routes.

- A pair of climbing axes – A traditional 'mountaineering'-style axe can still be useful for the easiest routes, but a general pair of climbing axes (nothing mega technical) is more versatile, one with a hammer and one with an adze.

- Crampons – Standard 12-point crampons, such as the ever-popular Grivel G12, will cut the mustard. Make sure they fit your boots.

- Boots – Are your boots designed for winter climbing or do you need to upgrade? B1-B2 boots may be sufficient for the easiest routes, but B3s are stiffer and are required once you move beyond easy gullies and ridges.

- Rack – I adapt my climbing rack for winter by replacing short extenders with longer ones, throwing in lots more hexes or bigger nuts, removing the majority of my camming devices and small nuts, putting in more slings and tat, and – depending on venue – adding in some pegs or ice screws.

- Clothes – When climbing it's common to be stationary in cold conditions for hours. A synthetic belay jacket is a must, and big gloves – gloves to climb in, and then gloves to belay in or to swap when the first pair gets wet. Don't underestimate the power of warm, dry gloves.

- Guidebook – Think about photocopying pages. No point having Ben Nevis routes if you're climbing in the Cairngorms.

- Rucksack - Is your hillwalking rucksack big enough to carry all the extra equipment? Everything needs to fit inside.

Recommended first routes

There are hundreds of possible beginner's routes throughout the UK. The most reliable conditions are to be found in the Scottish Highlands, but Grade I-II winter routes also come into nick throughout the English and Welsh hills in most years – although conditions south of the border are far more ephemeral.

An excellent list of beginner's routes can be found in this UKClimbing article: Grade I winter – 12 Must-Do Routes.

We've asked Samantha Leary to recommend two routes for the walker looking to get a taste of mountaineering terrain. These routes won't require a rope for most people, so are a good way of gauging if you're ready to take the next step. If these are well within your capabilities then it could be time to start learning some climbing skills.

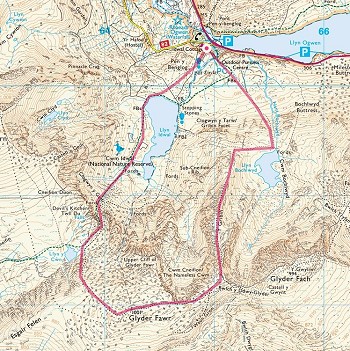

Glyder Fawr via the Gribin Ridge, Snowdonia

"This is a fantastic winter mountaineering day out. In good snow conditions, expect to use a mountaineering ice axe mostly for support, but on the steeper sections of the ridge itself you'll be using the axe and your hands to aid progress."

"The crest is very exposed, in places quite technical and very consequential. However you can stay below the crest and traverse along to the right some way below it – this gives superb short sections of scrambling requiring good route finding, movement skills, using your ice axe and crampons accurately and efficiently."

"Once at the top of the ridge the stroll to the summit is truly spectacular with amazing views over the Carneddau and Snowdon. If the visibility is poor, though, this will require accurate navigation – as will finding the correct descent."

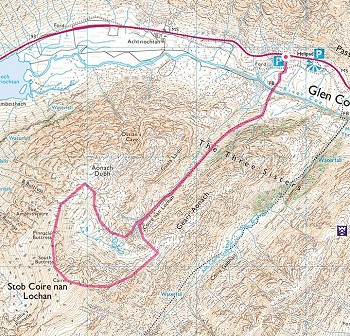

The Traverse of Stob Coire nan Lochan, Glen Coe

"The traverse of Stob Coire nan Lochan is a must. The walk up the valley is known locally as the 'Hurt Lochan': steep, but on an excellent path that tends to disappear under heavier snow. There are a couple of challenging steps on the way up."

"Once on the NE Ridge it's the perfect journey with sections of progressively more exposed and challenging rocky steps. You'll need to be accurate and efficient with your crampons and should expect to use the axe overhead occasionally. Simple but exposed terrain leads to the summit with one slightly steeper section just before the top."

"The summit provides mind-blowing views of snowy mountains as far as you can see. The descent requires care as it skirts the very impressive north-facing cliffs where you'll see other climbers at play. Be cautious of the edges – they often have cornices. Continue your traverse around the lip and then circle back around into the inner corrie to admire the cliffs from below. Then it's back down the path. A five-star day out!"

Why bother?

If you've read this far you might not need any more convincing, but I think Di Gilbert sums it up well:

"The Scottish winter scene is one of the biggest rewards out there. A fine line between a complete sufferfest and a complete joy. It's a love/hate relationship that I wouldn't change for anything."