After the Accident - How to Get Found Alive

If you're incapacitated on a Scottish winter mountain then your prospects depend on how well equipped you are, and how quickly you can be found. Roger Webb of Dundonnell Mountain Rescue Team looks at some simple measures that might help to stack the odds in your favour.

This article is not about how to avoid accidents - stuff happens. Here we're looking at your options after an accident, should you or your partner be unfortunate enough to have one, and how a little bit of planning might help to keep an unpleasant experience unpleasant, rather than fatal.

If you only climb or hill walk in good flying weather, at popular venues, with a phone signal, where help is at hand, you probably don't need to read this article. But if on the other hand you enjoy inclement weather, or going to the less travelled parts of Scotland, then it might be worth your while reading on.

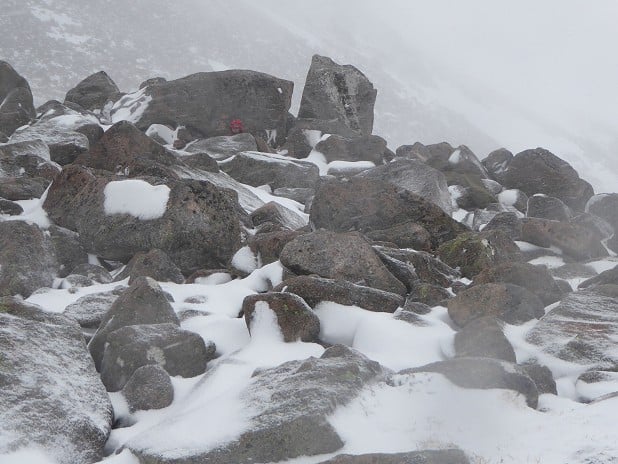

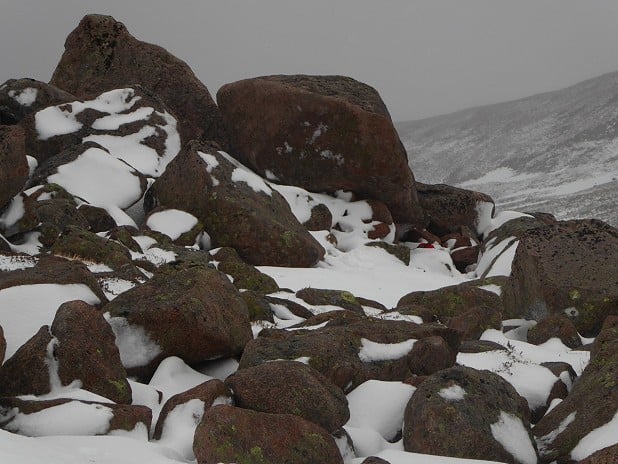

Searchers are looking for something that doesn't fit in the landscape. You don't have to be dressed like a Christmas tree - just don't dress like a rock or a ninja

In Scotland in winter, an accident that limits your mobility is life threatening; one that ends your mobility will be fatal unless help arrives.

Your survival depends upon three things:

- Communication

- Time to rescue

- Your ability to still be alive when rescued

Communication

Are you incapacitated, far out in the hills? No one is coming for you unless you or someone acting on your behalf asks them to.

There are two ways to contact rescue services, direct and indirect:

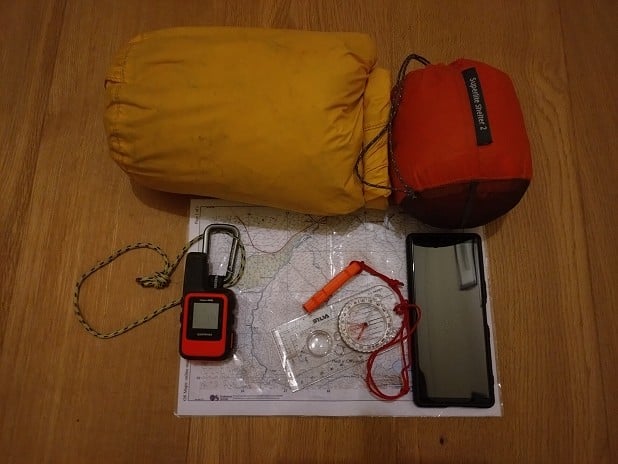

Direct methods include mobile phone, satellite phone, PLB and Satellite Tracker. All direct methods suffer from the disadvantage that you need to be able to use them after your accident. None, in direct mode, are of any use if you (and any companions) are unconscious, dead or sufficiently injured to be unable to reach them. These situations have occurred. If you have made no other provision for rescue you are in the same position as someone who has made none.

Of these methods the least reliable is the mobile phone. Mobile phones are vulnerable to not having a signal, having a flat battery, being frozen and accidentally being used as a crash mat (all have happened). The others tend to be more robust.

Indirect methods include satellite trackers where the track has been disclosed to a friend who knows when and how to call out a rescue, other satellite trackable devices, and detailed notes with the same provisos.

A note is a standalone, if you are using a tracker it is best to leave a note of intended routes, they are great for crags or general areas of hillside but less so for individual lines. You can waste a lot of time checking the wrong gully.

In order to be useful, any note you've left with a friend needs to be detailed: "Gone to do some routes on An Teallach" or "I'm climbing Braeriach" leaves a lot of ground to search in bad weather. Include where, when, estimated time of return (ETR), equipment and clothing colour at a minimum. In addition, it would really help if you could leave contact details of someone who really knows you and can make an informed guess as to where you are likely to be if not where expected. Twice in my experience this has or would have led to recovery sooner if only we had known who to ask.

If you change your plans, let someone know if you can.

All this does take some of the spontaneity out of life, but I speak as someone who went out to do Scorpion on Carn Etchachan and ended up doing Orion Direct on Ben Nevis. High on Orion Direct my friend broke his femur. As it was pre-mobile days, dark with rubbish visibility and no one else seemed to be on the hill the only solution was the fairly tough decision to abandon him and go and get help.

Unless it is absolutely necessary, I wouldn't recommend this. It's not fun.

Time to Rescue

This varies wildly and is subject to multiple variables, the most important two being the weather, and whether rescue services know where you are.

You should be equipped to survive at least until the next afternoon

If you have contacted rescue services directly with your location: If the weather is benign, good for flying and the helicopters aren't off on some other task, they are likely to be off the ground within 20 minutes of being notified - although another 30 minutes may have been used up reaching the decision to send them. Add flying time and you're looking at a couple of hours from first contact.

With the same caveats, if you don't have direct contact but are relying on someone else checking a satellite device you will have to wait the period before they initiate the callout and then add two or three hours.

If the weather is too poor for flying or for whatever reason a helicopter is not available, then you are awaiting a ground-based rescue. This is going to take a long time. Best hope you didn't overdo 'fast and light'.

While there may be areas in Scotland where a ground team can muster and get to you within a few hours there are lots of places where they can't. It's simple geography.

My own team, Dundonnell MRT, basically covers the 'Northern Highlands Central' SMC guidebook area plus the hills north of the A835 including Beinn Dearg and Seana Bhraigh. If you look at the map you will see that not a lot of people live there. The same applies for our sister teams in Kintail, Torridon and Assynt. Team members are dispersed around the settlements on the fringes of the areas. It will take us a couple of hours to muster and get organised. If it took you three hours to get to your location then it's going to take us longer, since we have more kit. Many crags in the northern highlands will take longer than that. Once you add in darkness and poor weather the time frame is getting worse.

Staying Alive

If you are heading for a remote crag then you should be equipped to survive at least until the next afternoon. Unless you have experienced the immobility that comes with a broken body it is hard to understand just how cold you get and how fast. It is that body you need to keep alive, not the fit healthy one you have now. You don't need to be happy and toasty, but better to still be shivering when help shows up.

Don't stack the deck against yourself. It would be a shame to die because no one knew where to look, or no one saw you, or because of a lack of kit

Everyone is different but to stay alive we all need to keep our core temperature up. Wind, cold and wet are your enemies. These are my views, others may disagree, but as a minimum I carry:

A bothy shelter. These days they don't weigh much. A bothy shelter alone is far superior to a bivi bag alone; you will only need to try to get into a bivi bag with a broken leg once to get the point.

A substantial belay jacket: you can supplement this without much extra weight with a blizzard bag or foil blanket.

I don't count belay jacket and headtorch as emergency kit. On any decent winter's day, they're going to get used.

Map and compass as emergency kit? For better or worse many people use some form of electronic navigation these days, which is fine, but only for as long as it is functioning.

Helping in Your Rescue

At this point, discounting the situation where you were in direct contact with rescue services in good flying weather, then you are now in the middle of nowhere trying to stay alive or keep someone in your party alive. Help is on the way, but it's got to find you. Is there any way you can help the help?

Help can be in three forms, or all three at once: A helicopter, MRT personnel on foot, and MRT personnel with SARDA (Search and Rescue Dogs Association) dogs and handlers.

Only the dogs don't care what colour your kit is.

Here are quotes from two coastguard helicopter winch operators based at Inverness:

"If you're wearing black you can be jumping up and down, but we won't see you from 500ft"

"Climbers aren't ninjas. We're no good at finding ninjas, so don't dress like one"

It gets more problematic.

Recently I went to a presentation by aircrew based at the Inverness rescue centre. I was struck by how limited a lot of the high-tech kit is. If you are very cold or very well insulated then the infra-red won't see you; if you are in trees, it won't see you; if you are in peat hags or a boulder field it will likely not see you.

A good friend of mine experienced this first hand. Standing with a group of four in radio contact with a helicopter that was actively looking for them they were overflown several times before being spotted. This wasn't because the crew weren't looking or were incompetent, it's just that spotting someone from a few hundred feet, whilst travelling at speed, peering through the distortions caused by disturbed air, is a lot harder than many fondly imagine.

Your best option, if you can see the helicopter, is a light. Daylight or not, a headtorch shows up a long way. A flashing one is better and a coloured flashing light even better still. The problem is, if you've been out for a while then you won't be sitting up looking, you'll be tucked away as far out of the wind as you can get. You won't hear the helicopter until it is on top of you.

The good news is that dogs are very good at finding ninjas, the bad news is they aren't always available or present. They may be looking for you in a different area, they may be otherwise engaged. Unfortunately, both scenarios have occurred and will occur again.

In the absence of dogs how can you help those looking for you?

Searchers, both airborne and on the ground, are looking for something that doesn't fit in the landscape. Three things stand out:

- Movement

- Light

- Colour

The first two require the casualty to be active, but the last does not. After you have been out for several hours it is likely that you won't be very alert or lively. You are likely simply to be lying there. Even if the rescue starts out with you in direct telephone contact with the team things can change. Your battery may go flat, you may slip into unconsciousness, you may die. All these things have happened in my experience and doubtless many times in that of others.

Clothing colour counts

It is unfortunately no good relying on your rucksack as, if you weren't killed outright, you are probably sitting on it. If you're not, you should be.

You don't have to be dressed like a Christmas tree (although that would help!) just don't dress like a rock or a sniper.

Does it really make a difference? Yes. I can think of a few who have been found because of a splash of colour and a depressing number who were never found - all of whom seem to have been in dark-coloured clothing. I know that I once passed within about 20 or 30m of a casualty who sometime later was recovered as a fatality. He was wearing dark green. Whether or not my seeing him would have made a difference I will never know.

Where am I going with this?

No one is saying dress as a flashing beacon, well I'm not at least; or don't take risks - life would be a bit colourless without. I am saying be aware of the possible consequences of your choices and that some quite simple choices, that have no real downsides, can mitigate those possible consequences.

Don't stack the deck against yourself.

It would be a shame to die because no one knew where to look or no one saw you or because of a lack of kit. Every year that happens to somebody. Whilst there are places in the world where rescue isn't an option, I've certainly been to a few, there are no such places on the hills and crags of Scotland.

Stack the deck in your favour. It doesn't take much.

There's a lot of adventure to be had in Scotland. Go to the wilder places, have fun, but do consider the possibilities if things don't quite go to plan.

About Roger Webb

Roger has been winter climbing since the late 70s and has done several hundred new winter routes. Many of those are in the more remote parts of Scotland. Sometimes he climbs in summer. He has also climbed extensively in the Alps and done a bit in the Himalaya.

He has been involved in mountain rescue for 14 years, and is currently Deputy Team Leader of Dundonnell MRT.

"During the past 46 years, I have been both the rescuer and the rescued" he says.

"These experiences, particularly that of finding the dead who might have lived, have formed my opinions. Others may have different views on some aspects and different attitudes to risk. That is their right and I do not say that they are wrong, but these are my opinions. Nothing is prescriptive."

Acknowledgements to:

Neil Adams, James Gordon, Hamish Irvine, Dave Kerr, Mark Lean, Donald MacRae, Fiona Neilson, Iain Nesbitt, Mark Robson, Scott Sharman, Alison Smith, Neil Wilson, Steve Worsley, Conor Brown and Simon Richardson

Further reading: