Part 1. What, When and How?

The UK's Big Three hill rounds are lifetime ambitions for many runners, not to mention these days ambitious backpackers, but their magnitude can seem overwhelming. In this article series we look at the many options and tactics that might make the experience a little easier. From the best time of year to do it in, to your approach to support and logistics, this first part of the series tackles some of the key basics to consider in the early stages of planning a round.

Make of these routes whatever you wish. Contrary to what some may tell you, there is no right or wrong way to do any of them. The key is finding whatever solution works best for you, be that a sub-24-hour solo mission, a sociable run supported by friends, or even a multi-day backpacking journey.

What are they?

This article was written with the UK's 'Big Three' in mind:

The Bob Graham, the Paddy Buckley and the Charlie Ramsay.

Of course many other rounds exist, and you can make up all manner of routes yourself. A lot of what is written here applies to any long and challenging hill route, but in this article we'll specifically focus on the three most famous.

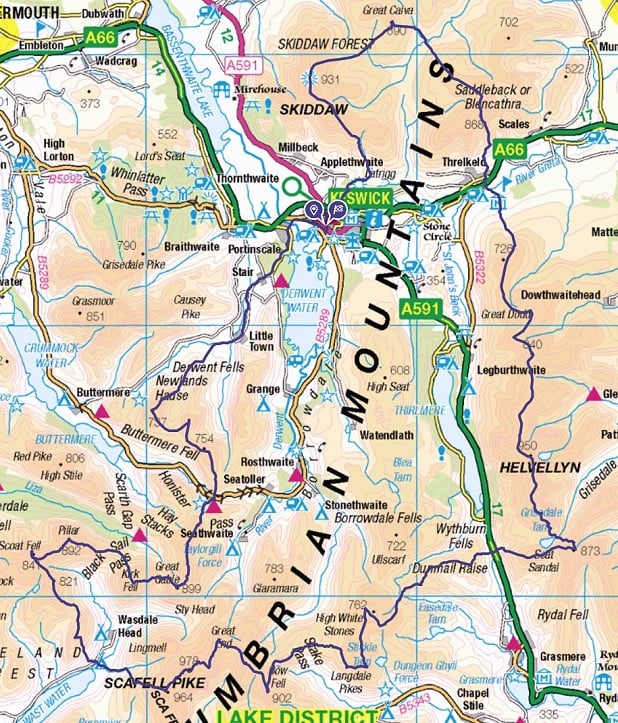

Bob Graham Round

Lake District

Distance: 98.8km (61.4 miles)

Ascent: 8160m (26,778ft)

The Bob Graham round of 42 Lakeland peaks (including the four 3000-ers) is the best-known fell runner's challenge in the country. Wearing tennis shoes and fuelled on bread and butter the man himself set the bar high way back in 1932 and his time of 23 hours 39 minutes stood for 28 years.

This is the most popular of the three by far. There are many reasons for this, but the first - and potentially most obvious - is that the Bob Graham was the original 'big round' and is firmly rooted within the heart and soul of British fell running in the Lake District.

Because of its popularity it is the easiest for which to find support. Not only are there many people wanting to do it each year, but those who have done it often want to give something back by way of helping others, and there's a fantastic sense of community.

Whilst it is considered to be the easiest of the Big Three, I am hesitant to use the word 'easy' in reference to any of them, because they're not. I personally found the Bob Graham just as hard as the Paddy Buckley and the Charlie Ramsay, mostly because unlike the others - it's incredibly runnable. If you're good at running, and have the legs to keep going, the Bob Graham definitely has the potential to be the fastest of the three, but if you don't - or your strengths lie elsewhere - it could be worth considering the other options, just in case they suit you a little better (unconventional though that might seem).

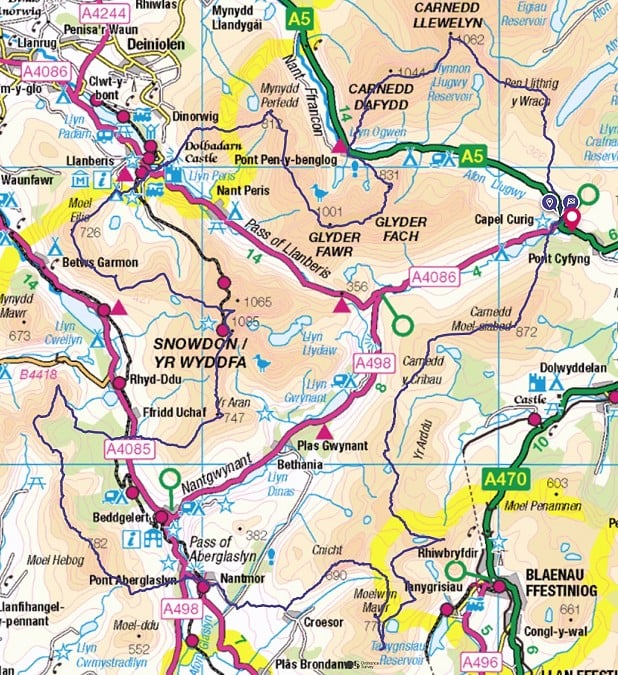

Paddy Buckley Round

Snowdonia

Distance: 100.5km (62.4 miles)

Ascent: 8,700m (28,750ft)

A circuit of 47 summits in Eryri (Snowdonia), the round was devised by Paddy Buckley but first run in under 24 hours by Martin Stone in 1985. The route includes the Carneddau, the Glyderau, the Snowdon range, the Moelwynion and the Moel Hebog range.

The Paddy Buckley is often touted as being the hardest of the three. It's easy to see why from the stats: it's not only longer, but it also features far more elevation. If this weren't enough, the terrain is also a lot rougher than the Bob Graham's. Whilst its popularity has grown in recent years, it's still nowhere near as popular as the Bob Graham, so finding people to recce with, and a team to support you on the attempt, can be more of a challenge.

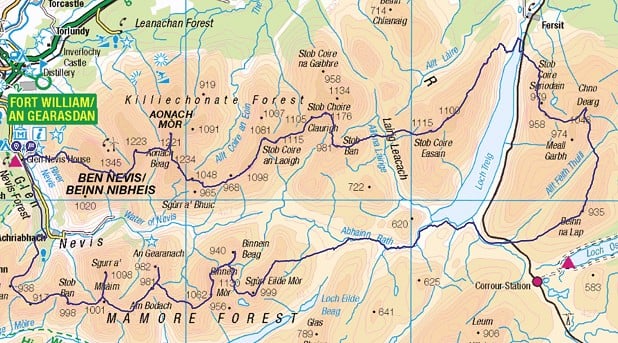

Ramsay Round

Lochaber

Distance: 92.8km (57.6 miles)

Ascent: 8,800m (28,979ft)

An extension of an earlier effort by Philip Tranter, Charlie Ramsay's amazing effort covers 24 Lochaber Munros, with high points on the four west coast four-thousanders Ben Nevis, Carn Mor dearg, Aonach Mor and Aonach Beag. But that's just the start (or finish) of it: you've also got to traverse the Grey Corries, the Easains and Loch Treig Munros and the whole Mamores ridge. Ramsay just scraped inside the 24 hour limit in 1978.

When it comes to logistics, none are as challenging as the Charlie Ramsay Round. Whereas the Bob Graham and Paddy Buckley are split into relatively nice, manageable sections, interspersed with accessible road crossings, the Charlie Ramsay is not. In fact, the only road you cross is the one you start/finish on!

As a result of its inaccessibility, reccying is much more of a challenge - something that is further complicated by the fact that snow can also limit amount of time it's both safe and practicable to be out on the hills. A winter Ramsay round is a mountaineering expedition, not something open to runners without the relevant skills and experience. If its remoteness isn't already sounding difficult enough, then it gets worse: the Charlie Ramsay also features the roughest terrain of all three (and does so by some margin), has the fewest trods, and the most height gain/elevation.

Which is the one for you?

Whilst there's no denying that the Bob Graham has convenience in its favour, this doesn't necessarily mean it's the right one for you. Perhaps you'll like the sound of the wilderness of the Charlie Ramsay Round or the diversity of terrain on the Paddy Buckley; or maybe you just happen to be based closer to one than the others.

It's worth assessing your strengths too, because if you do happen to favour rough terrain, then there's a possibility that you'll get on better with the Paddy Buckley and Charlie Ramsay, compared to the relatively fast, runnable ground on the Bob Graham.

Another question worth asking yourself before you decide, because it may turn out to be an influencing factor, is this...

Do you care about doing it sub-24 hours?

Whilst these routes are often thought of as 'sub 24 hour challenges', and that certainly has its rewards, I genuinely think it would be positive for people to let go, or loosen this concept a little, and be more embracing of the fact that doing these rounds in over 24 hours is still an amazing effort.

There is a great satisfaction and lasting pride to doing a big round, full stop, whether that be under 24hrs, over 24 hours, or across several days. Hopefully by doing this it will actually ease some of the pressure on the route itself, as people no longer feel the need to over-recce each section, aiming to make ever more marginal gains, which has led to significant erosion (eg the path/trod up to Clough Head, which is now visible from space).

There are as ever a couple of caveats to this. If you want to join the Bob Graham Club, for instance, then you have to do it in under 24 hours (and have witnesses on each of the summits). If this means a lot to you, then that's what you should aim for. But if it doesn't - do it in whatever style most grabs you. It's worth noting that unlike the Bob Graham, neither the Paddy Buckley nor the Charlie Ramsay Round stipulate that completion within 24hrs is mandatory to say you've "done them".

Completing a big round is an incredible life achievement, irrespective of the time it takes you. Don't be afraid to set your own rules - just be honest (and proud) about however you decide to do it.

This article has been primarily written with people doing a single push in mind, but there's also no reason why you can't do any of the big rounds as a multi-day expedition. They are logical routes, after all, which would represent a compelling challenge for keen hillwalkers and backpackers. Setting off on any of them with an overnight pack would make for a tremendous and unforgettable trip, and the fact you did it over several days would - if anything - give you more time to enjoy being out in the superb mountain environment. The only downside would be the amount of kit you'd have to carry!

What style do you prefer?

It ought to be clear by now that there are many different ways to approach a big round. Some people feel very strongly about one way over others, but how you do it is entirely up to you.

I've outlined various approaches below, but in addition to these you have the choice of completing a round in either summer or winter (or both, if you're some sort of a sadist). This article is aimed at summer, partially because if you have the competence to be looking to do a winter round then most of what we've written should already be familiar to you. There's also the matter of whether or not you wish to do them clockwise or anti-clockwise, yet another of those personal questions with no single right answer.

Solo/Unsupported

Running on your own, without support or pre-stashed bags

Pros: the ultimate in terms of purity, which does have a major benefit - flexibility. There's no one to be relied on other than yourself, hence it's easy change dates to get the best weather window possible.

Cons: also the ultimate in terms of difficulty, as all navigation and decision making falls upon your shoulders, plus there's the extra weight to carry throughout, and safety to be considered if something does go wrong.

Solo/Self-Supported

Running on your own, with drop bags pre-placed in key positions, by yourself beforehand

Pros: a very flexible approach, which - much like solo/unsupported - gives you the ability to shift things so that your attempt fits in with a weather window.

Cons: has the potential to be a massive faff, as you drive around wherever it might be - the Lakes, Snowdonia or Lochaber - stashing your bags when you'd potentially be better of resting (or running).

Solo/Supported

Running on your own, but with outside support at key points

Pros: organising one or two people to meet you at the roads is relatively easy in comparison to organising a full team. It's a bit less lonely than a full solo mission, as you do get to see people, and also a bit safer due to the fact that there is some (albeit minimal) support waiting for you at certain key points.

Cons: requires a little more admin, but still demands you navigate your way around, and carry everything you need.

Supported

Running either with another person or people, with further support at the roads

Pros: this is without doubt the most social, and potentially the most fun way to complete a round, plus it has the benefit of having a much greater chance of success too, as you have a pace set and people to carry all your kit and navigate.

Cons: it requires quite a lot of organisation and makes you a little more fixed to an individual date, which has the potential to be a good thing (because it makes it real) and a bad thing (because you can't guarantee good weather).

Guided

If you haven't got the time to pace other people, but want a pacer, this is an option, albeit quite a contentious one, as it's perceived to go against the ethos of the spirit of the round

Pros: guarantees top quality support, from someone that knows the round, the pace and what's required for you to make it.

Cons: is this really what you want? In the case of the Bob Graham, guided rounds will not be accepted into the Bob Graham Club

Time of Year - when is best to give it a go?

On paper, the best time of year to do a Big Round is around the longest day, when you've got plenty of daylight and the weather and underfoot conditions are - at least in theory - more likely to be dry.

There are a few obvious caveats to this, with the first being that British weather is extremely fickle and it's worth building contingencies into your plan around this.

So what if it's a washout? Advice on this subject tends to vary, with some people saying to "give it a go regardless of what the weather is doing" and others - including myself - erring towards "leave it until another day, when you'll be more likely to have fun". Most of the people I've supported on rough days have had a tough time. If you do decide to proceed, you'll no doubt have a day to remember, but if you opt to postpone just make sure you can another date pencilled in ASAP, as you don't want to lose momentum with your attempt.

The other issue with going close to the longest day is that it can be very hot, which presents different but no less problematic issues than too much rain. None of the rounds have meaningful shade, so there's no escape from the heat, and when heat stroke hits - it hits hard. There are ways to help mitigate this (i.e. drink a LOT of water, and keep topping up the electrolytes), but don't underestimate the difficulty it adds. Heat does have its uses though, with prolonged sunshine drying out the ground to make it more runnable; however, it can also dry up some of the streams you'll need for refreshment along the way.

It's also worth looking at what state the moon is in, because a full moon is a massive benefit overnight, as it provides you with a lot more light. Of course, in order to make the most of this it needs to be cloud-free - which isn't always the case - but it's worth being aware of and planning around it, if you can.

It may seem a fruitless task to attempt to summarise seasonal weather conditions, given how unpredictable it always is. But here's a broad generalisation of some of the pros and cons of each of the most suitable months:

- April*

- Pros - can get some nice, cool conditions (if you're lucky)

- Cons - a lot less daylight, could actually be quite cold

- May*

- Pro - traditionally a good, stable weather month in the mountains

- Cons - slightly less daylight, but not by much

- June

- Pro - a similarly good month to May, but with even more daylight

- Cons - can be quite warm, midges start to become a problem

- July

- Pros - still a good amount of daylight

- Cons - more midges, more rain, roads likely to be busier with tourist traffic

- August

- Pros - very few...

- Cons - less daylight, midge situation close to unbearable, roads likely to be busier with tourist traffic, vegetation at its highest

- September

- Pros - tends to be a bit cooler than the summer months, with more stable weather

- Cons - a lot less daylight, vegetation will still be quite high

* In spring it can still be winter on the Scottish hills. Significant snow patches can persist into May or June on the Charlie Ramsay Round, which may effectively write off an early season attempt - unless you're wanting to do it with axe and crampons.

One thing is for sure though: you're never going to get perfect conditions, and if you're waiting for them there's a distinct chance you're going to be waiting a long time.

Etiquette and environmental considerations

Our presence within the upland environment always has some impact.

One thing I always advocate is the principle of "be nice, say hi". Consider yourself an ambassador for the big rounds whilst you're doing them. People are often fascinated as to what you're doing and if you can't explain, get one of your support to. It'll genuinely make someone's day. In the valleys, the noise we make close to people's homes can be heard, and is unlikely to be welcome in the early hours of the morning, so if you're a foghorn (like me) - remember to turn it down a notch.

When it comes to the environment, there's no denying that the increase in popularity of the big rounds has had a marked effect on the obviousness of the tracks and trods that are taken. Nowhere is this more obvious than the Bob Graham, where the line up Clough Head, in particular, represents something of an eyesore. An article such as this could be seen to make matters worse, as these things don't need to be more popular; however, the issue - in my eyes - is more complex than just the number of people doing it. The obsession with doing it in under 24 hours leads to people over reccying, so rather than running it just once or twice beforehand, they cover the ground many more times. Each visit means footfall and erosion. Add into the mix a gang of pacers, with some parties taking four or more on each leg, and there's going to be a far greater impact.

Whilst I'm not advocating everyone does it onsight, solo, what I am saying is that we do need to consider our impact. I also think we should move the focus away from the Bob Graham a little as 'the round' to do and open the doors to the others. Whilst neither of those is without issues, if you approach them in a sympathetic and subtle way (i.e. don't over reccy and consider the amount of support you receive) then the level of wear should be more balanced.

It should go without saying: follow the Countryside Code in England and Wales, and the Scottish Outdoor Access Code north of the border.