Mountain Literature Classics: The Shining Mountain

Forty years ago this month, Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker died on Everest. Written by Boardman, with additions from Tasker, this gripping account of the pair's celebrated first ascent of Changabang's fearsome West Wall captures the utter commitment of cutting edge 1970s Himalayan climbing. After many failed attempts, their route was only repeated in May 2022.

T

he 'Silver Age' of Himalayan mountaineering starts on 2 May 1964, with the knocking off of Shishapangma, the last of the 8000-ers. The most dedicated climbers then turn to smaller teams, lightweight and often alpine-style, on difficult routes in the greater ranges. One of its defining stories is the ascent of Changabang by Pete Boardman and Joe Tasker in the autumn of 1976.

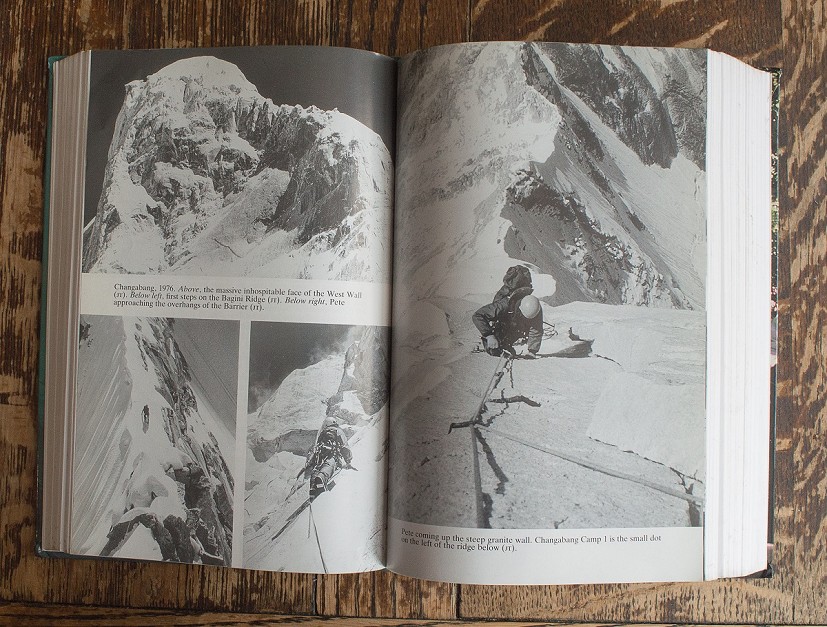

Changabang (6864m): it's one of the 'Glaramara' mountains – Ama Dablam, Nanga Parbat, Ararat. But it's not just the spelling that's special. It's a great rock tower the shape of a frostbitten thumb. Its west face is 5000ft high and pretty much vertical. Many considered it either impossible, or unjustifiable.

"It doesn't look like a married man's route" – Ken Wilson, editor of Climber magazine.

"I'd take an extra jumper" – Doug Scott's way of saying much the same thing.

For someone who doesn't climb at such high levels, it's a heart-stopping moment when an extreme athlete achieves the seemingly impossible in a single leap, like Superman out of his phone box. I mean, of course, the moment when they decide that this 2000-mile trek or near lethal mountain is what they're going to do. "I knew I must go… I wondered if I would come back," Boardman writes. "My mind took a great leap and accepted the whole project."

Pete Boardman was the National Officer for the BMC. Joe Tasker, with no fixed career, was working night shift in a cold store where he could handle ice cream and éclairs at –15° without gloves as useful expedition training. Each had major ascents behind them: the two had met while sharing an epic retreat from the Droites, above Chamonix. "Just 2 of us would make the dangers and decisions deliciously uncomplicated."

Lightweight, alpine-style ascents of difficult routes in the greater ranges: can this be said to be the purest and most perfect form of mountaineering? Unfortunately, the survival rate is rather low.

And this question runs through Boardman's story like a bright yellow thread in a climbing rope. Just why are we doing this? It's explicit in discussions with their Indian liaison officer, Flight Lt DN Palta: "I still don't understand how you chaps justify this climbing…"

And Boardman's unconvincing reply. "It can develop your character," I said, "and make you more independent and hold things in more realistic perspective. The travel to the mountains as well as the mastery of mountaineering technique enlarge your experience so that you are more effective and interesting if you ever teach others, or even when you just meet people… Exploring human potential, finding things out about areas that are hardly known… Anyway, I think any enthusiasm or interest is better than none at all. And," I added defensively, "I enjoy mountains!"

The thematic thread reappears as Boardman mentions a warning to bus drivers above the dangerous gorges on their approach ride: "Life is short. Don't make it any shorter." Again, on p48, when Nanda Devi Unsoeld (daughter of Willi) dies on Nanda Devi just as they're looking up at the mountain on their approach march.

The brightest flowers grow on the borderland of Death

That's from Frank Smythe, Everest afficianado from the 1930s. I can't trace the quote, but maybe he's referring to moraines beside glaciers as well as, metaphorically, tagging this book 50 years ahead.

Pete Boardman had a degree in English Literature, and he writes with a simple directness. There are moments of joy – not that common in Himalayan mountaineering. The elegant Bagini ridgeline, a knife-edge arête resembling one of the really great Alpine ADs (the north ridge of the Weisshorn, say). The clean, white granite with its crystals of muscovite and tourmaline, like Chamonix but bigger, free climbing and aid up through the overhangs. The 'ridiculously steep' icefield, and the arrival through a keyhole onto the summit snowfields.

But death is always there at his elbow. Writing the diary that'll be left behind at base camp, he censors out their occasional disputes and disagreements: he doesn't want to supply those who might find it with "reasons behind the tragedy"… Or the fixed rope through the overhangs, with its awkward knots and anchors – named as the Toni Kurz Pitch, after the climber who died in a tangle of abseil ropes on the Eiger. And finally, shattering the elation after their climb, they turn back up the glacier to recover the bodies of four Americans who'd been climbing next-door Dunagiri.

Many of us, in some wet bivvy, on some interminable scree, on crumbly rock with no protection – many of us ask ourselves: are we mad to be up here? But Pete Boardman thinks it through, even attempts to answer the question.

Even though it doesn't actually have an answer.

They get off the train at Manchester to be greeted by a welcoming crowd – a rather small crowd of blue-uniformed workers from Joe Tasker's cold store. Joe goes off to the ice cream and éclairs, Pete gets a night's sleep before heading in to the office.

Boardman and Tasker, a dream team for this sort of mountaineering, went on to climb together on K2, Kangchenjunga and Kongur. Forty years ago this month they set off up the northeast ridge of Everest, watched from below by Chris Bonington. They were last seen high among the pinnacles at 8250m. A Japanese-Kazakh expedition came across Pete Boardman's body in 1992; Joe Tasker has yet to be found. Also this month, after 20 failed attempts, their route on Changabang was finally repeated by a team from New Zealand.