Mountain Literature Classics: My Climbs in the Alps & Caucasus by Albert Mummery

There are books you can come back to many years later, and find whole new levels of meaning and significance. Those books tend to be the classic novels, or perhaps the plays of Shakespeare. Not books about climbing. But is this an exception?

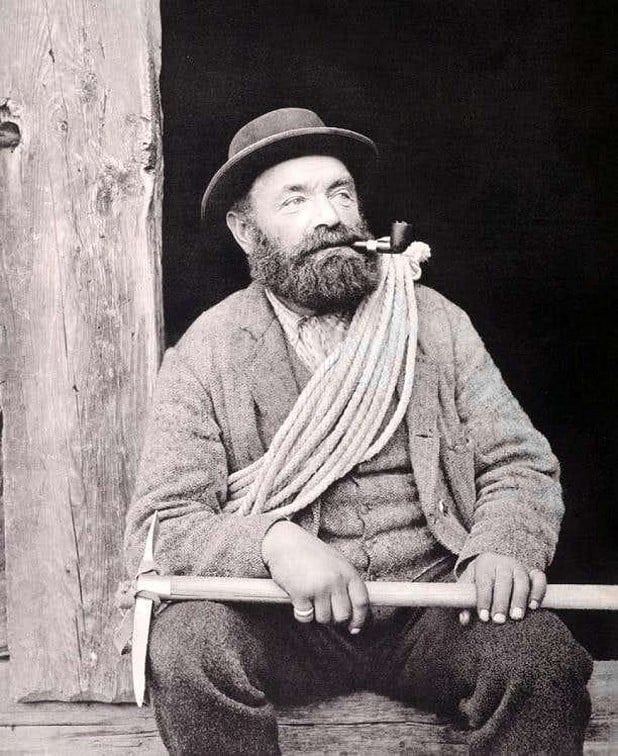

On first reading, 'My Climbs' by Albert Mummery is an exciting account of early Alpine ascents. And in that genre it's possibly supreme (I write 'possibly' as I haven't yet read Leslie Stephen, the early mountaineer who was also Virginia Woolf's Dad). By the 1880s, the easy and obvious mountains had been climbed and the Hörnli ridge on the Matterhorn had become a trade route. In partnership with friends such as Cecil Slingsby (him of the chimney on Scafell) and Norman Collie (he of Collie's Ledge on Skye); but more particularly the guide Alexander Burgener, Mummery was seeking out "the most difficult routes on the most difficult mountains". And he wrote about them in a vivid and fun-loving style, laced with Victorian wit.

Their climbing was at a level of danger found today on Alpine-style climbs in the greater ranges. Exploring took them up the classic routes – the first ascents of both the Zmutt and the Furggen ridges on the Matterhorn, the Aiguilles de Charmoz and Grépon. But you don't find the Furggen without also explorations of less satisfactory ground. The Col du Lion, at the foot of the Matterhorn's Italian ridge, was undertaken because "no more difficult, circuitous, and inconvenient method of getting from Zermatt to Breuil could possibly be devised than by using this same col as a pass". The ascent was on loose rock, black ice and unstable snow. Crampons, remember, have yet to be invented. This is all to be done with step-cutting, with the rope for reasons of solidarity. If the leader should slip, the second man would be following him down into the bergschrund. But the really stimulating aspect was the stonefall. By half way up the gully, and the sun shining, the lower part was being bombarded from the slopes of the Matterhorn, greatly motivating the completion of the climb.

Taken on its own level – that level being around the 4000m contour – this is a classic of Alpine writing, especially if you fancy some of these climbs in today's much easier conditions of guidebooks, proper protection, and ropes that don't break. And perhaps it's just me, on re-reading, to find also a fascinating character study. Fascinating because unresolved. Mummery a Victorian English gentleman, member of the exclusive Alpine Club, complete with sense of entitlement, the appropriate class prejudices, and a public-school sense of humour. And Alexander Burgener, speaker of Schweizerdeutsch, son of a peasant farmstead somewhere below Saas-Fee. Burgener very sensibly insisted on some training climbs first to find out if this fellow could climb. But within five days they were sharing the first ascent of the Zmutt.

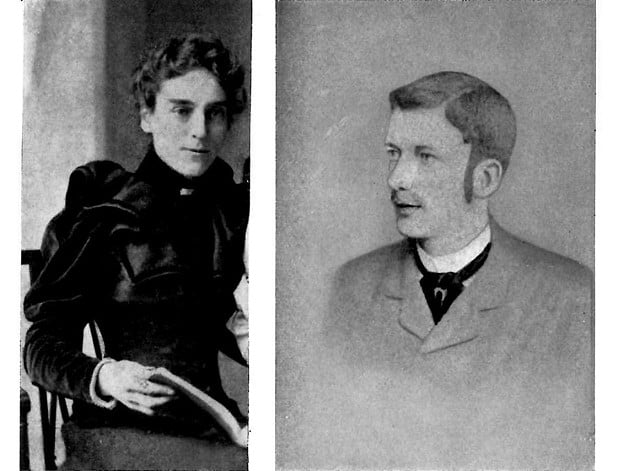

And then there's Mrs Mummery – her first name was Mary, though this isn't revealed in the book – along with her friend Lily Bristow. Burgener invited Mary Mummery along on the first ascent of the Teufelsgrat on Switzerland's second highest mountain, the Täschhorn, and she gets to write the relevant chapter. It's a ridgeline like a Disney cartoon, a few centimetres wide with vertical sides dropping 600m on either side. Today it's graded D for Difficile, with rock pitches graded V, and reckoned to take 8 hours for modern climbers with modern gear starting from a bivvy at 3638m. Burgener and the Mummerys started from Randa at the valley floor (1409m) at 1.30am after a night practising Strictly Come Dancing a century and a half too soon.

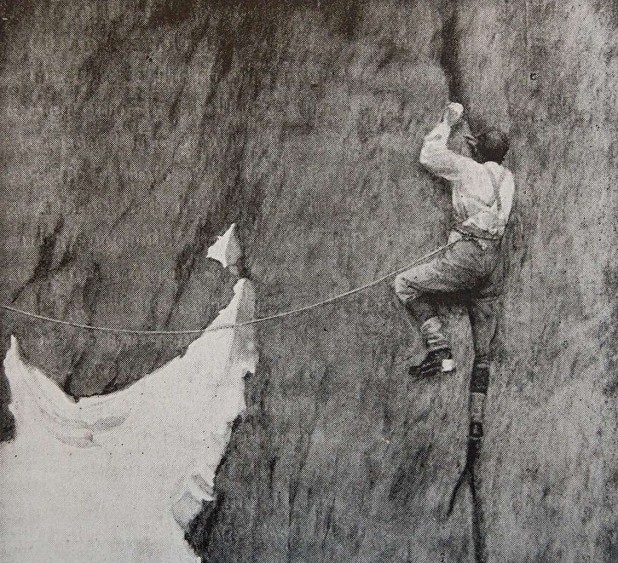

Meanwhile Miss Lily Bristow scandalised respectable climbers by sharing a mountain tent with Mummery and his friend Hastings as a high camp before an early re-ascent of the Grépon. She took the photo of Mummery in the so-called 'Mummery Crack', using a massive half-plate camera, then "showed the representatives of the Alpine Club" – which of course did not admit women – "the way in which steep rocks should be climbed". And that's about it for Lily. She wrote an article about the Dru accepted by the Alpine Journal. And she may be the model for Lily Briscoe in Virginia Woolf's 'To the Lighthouse'. According to Litcharts.com, "observant, philosophical, and independent, Lily is a painter pitied by Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay for her homeliness and unattractiveness to men."

In 1895, Mummery was about 50 years ahead of his time by becoming the first mountaineer to die on an 8000m peak – caught in an avalanche while attempting the Rakhiot Face of Nanga Parbat. Herman Buhl, who made Nanga Parbat's first ascent nearly 60 years later, described Mummery as one of the greatest mountaineers of all time. Mummery's book – plus Mary's contribution – is the defining account of what's called the Silver Age of Alpine Mountaineering. With just one niggling doubt – I do still need to read that Leslie Stephen.