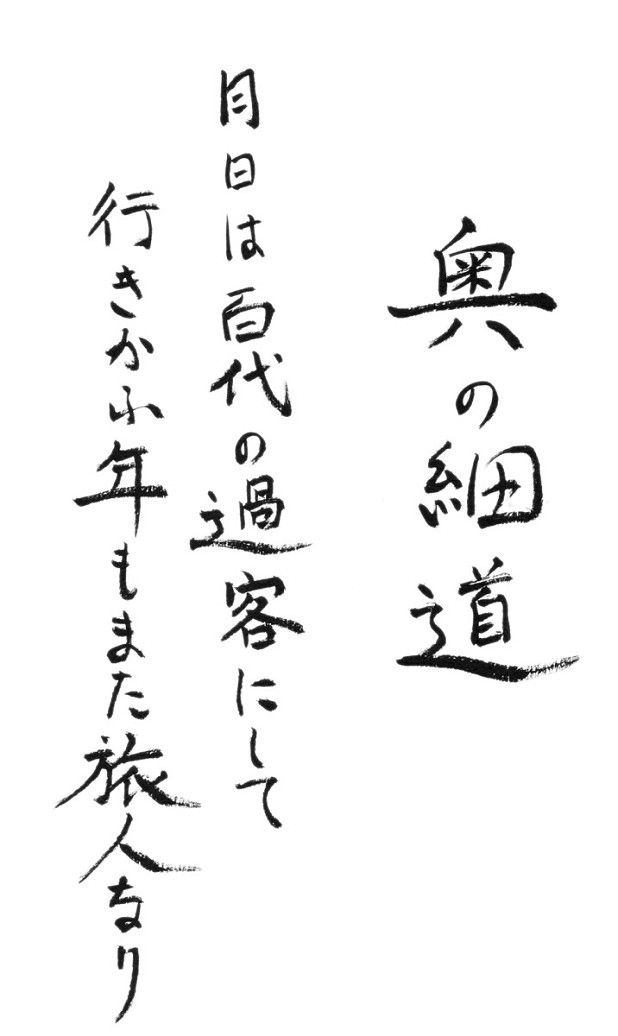

Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North

More than a century before the romantic poets strode the British landscape in search of the sublime, a Japanese writer made months-long journeys on foot, motivated by remarkably similar urges. Basho's walks have everything we recognise from our own multi-day hikes, says Ronald Turnbull.

Clouds move on the wind

I know I have to walk

by the sea, northwards

I've traced our tradition of serious hiking to the nine-day journey of the poet Coleridge in August 1802. But the idea of setting out on a very long walk, for the sake of – well, for the sake of whatever it is we go on long distance walks for. It happened here, and it also happened in Japan. In 1689, 113 years before the English Romantics and 6000 miles away, a different poet was setting out on a long walk of his own.

People who go on months-long walks, through dangerous country, purely for our own amusement: are we necessarily bananas? In Basho's case, yes. His writing name comes from his favourite plant, the non-flowering banana Musa basjoo.

In a way it was fun

not to see Mount Fuji

in foggy rain

Here he's just setting off from Edo (now Tokyo) on the first of his four long walks, recounted as 'The Records of a Weather-exposed Skeleton'. The Penguin edition has all four of the expeditions, translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa.

How far must I walk

to the village of Kasajima

on this endless muddy road

of the early wet season?

- Narrow Road to the Deep North

Basho's walks have everything we recognise from our own multi-day hikes. The complaining about the weight of the pack – after the first fortnight he throws half his load away. The overnight accommodation, both good and bad, not to mention absolutely awful.

Asleep in the straw

Fleas, lice

The horse pisses beside my pillow

- Narrow Road (RT transcription)

Before setting out on the Narrow Road to the Deep North of Japan, Basho sold his house and wrote his will. The trip would be 156 days from Tokyo, 2400 kilometres, taking in any mountains that happened to have temples on top.

But what was he walking for? And was it the same as what Coleridge was after, and us lot are after today?

Basho took in historical sites and famous viewpoints – the 17th-century Japanese version of Instagram hotspots. However, the important bits of Basho's trip journals are the three-line poems called haiku. Which is well known as a sequence of five syllables, seven, and five again. But also, haiku has to be about the natural world. It even contains a 'seasonal word', a clue (cherry blossom, brown leaves, icicles) as to the time of year. And what Basho was after in his haiku was a specific landscape sensation: the sensation known as sabi.

kono michi ya / yuku hito nashi ni / aki no kure

on this path or road

nobody is travelling

evening, in Autumn

- RT transcription

sabishisaya / hana no atari no / asunarau

Loneliness —.

Standing amid the blossoms,

A cypress tree.

Sleeping on a grass pillow

I hear now and then

the night-time barking of a dog

in the passing rain

- Records of a Weather-exposed Skeleton

Tell me the loneliness

of this deserted mountain

the aged farmer

digging wild potatoes

- at Bodaisan, Records of a Travel-worn Satchel

Always, Basho was working on the Japanese art of landscape appreciation. Which means, being on the lookout for sabi: isolated houses in the mountains or an empty moor in autumn. And in April 1688, he found it at Suma bay, 25km west of Osaka:

It was the middle of April when I wandered out to the beach of Suma. The sky was slightly overcast, and the moon on a short night of early summer had special beauty. The mountains were dark with foliage. When I thought it was about time to hear the first voice of the cuckoo, the light of the sun touched the eastern horizon, and as it increased, I began to see on the hills of Ueno ripe ears of wheat tinged with reddish brown and fishermen's huts scattered here and there among the flowers of white poppy.

At sunrise I saw

tanned faces of fishermen

among the flowers

of white poppy

- Records of a Travel-worn Satchel, final scene

Sabi is translated as loneliness. Which is the ordinary emotion that maybe comes closest to what the Japanese of the 17th Century were after. A state of silence, of emptiness, within the landscape. The landscape-baggers of England, 150 years later, were after what they called the Sublime: the special mental state when standing before a waterfall, or on a cliff edge in front of clouded empty spaces.

But whatever the word for it – on Mickledore at sunset, when all the other walkers have gone away – somewhere in the Rough Bounds, with nothing but mountains stretching into the distance – in blowing cloud on Crib y Ddysgl – or at daybreak on a beach on the south coast of Japan – Sabi, or the Sublime. Whatever it is, we maybe think we know what they're on about.

As firmly cemented clam shells

fall apart in Autumn

so I must take to the road again

Farewell, my friends.

- Narrow Road to the Deep North, final lines