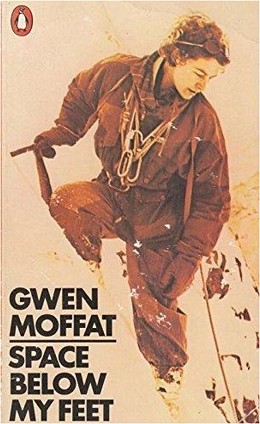

Mountain Literature Classics: Space Below my Feet by Gwen Moffat

In 1947 a nice middle-class young woman called Gwendolyn* Goddard deserted from her job as dispatch rider and lorry driver in the army to live rough, and technically on the run, in Cornwall and Snowdonia. Well, she had just discovered the climbing on Tryfan's Milestone Buttress…

For five months she never slept in a bed, but out in the open with an ex-army gas cape as a bivvy bag. She lived on £1 a day, by informal guiding, casual farm work or posing as an artist's model. She seems to have enjoyed more love affairs than hot baths. Never heard of Gwendolyn Goddard? Maybe under her first married name, which was Gwen Moffat. (*Sorry about 'Gwendolyn' – she's never been called anything but Gwen.)

"On the first morning, I took them up Middlefell Buttress: five of us, all on one rope. It was slow, cold and boring. They climbed faster than I did, surrounded with an almost visible aura of masculine resentment. So I took them to Gwynne's Chimney on Pavey Ark, and as they struggled and sweated in that smooth cleft, sparks flying from their nails, and me waiting at the top with a taut rope and a turn round my wrist, I knew that I had won. The atmosphere – when we were all together again – was clean and relaxed."

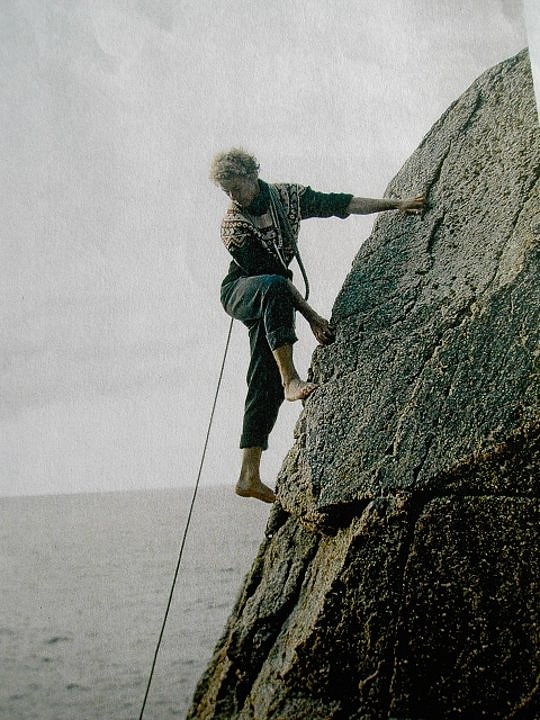

Moffat was leading Hard Severe and climbing VS, which In the 1950s was the hardest grade there was. This was the time when ropes were hemp – nylon ones existed, but she couldn't afford them. Belaying was around the body, with nasty rope burns for the second if the leader fell (especially if the second were wearing a bikini). Boots still had clinker or Tricouni nails in them, and while climbing shoes soled with felt or rope were just coming in, Moffat climbed as often as not barefoot – especially effective on Skye gabbro, she says.

For five months she never slept in a bed, but out in the open with an ex-army gas cape as a bivvy bag

For a while she rented a cottage on Loch Harport looking across at the Skye's Cuillin hills, living on nettles and wild garlic, warmed with hand-cut peats, sharing the house with a troop of rats and whatever human climbers might happen along. They set out to attempt the record for the Cuillin ridge traverse – the record for slowness. With a planned bivouac on Sgurr a' Mhadaidh, in a summer snowstorm,had one oilskin and one sleeping bag between two, and hardly any food. "I had adventure – better than any jungle or desert – every time I put my foot on rock."

When writing up your climbing adventures, you tend to home in on the benightments and bivouacs. Even so, there do seem to be a lot of them in Space Below my Feet. A winter night on a small ledge of the Aonach Eagach; another crouched below an overhang low down on the Zinal Rothorn; a winter bivvy on the Glyders. When it comes to a winter climb on Ben Nevis – Observatory Ridge, say – there are climbers who sensibly set out at dawn, and there are other climbers who get moving around mid-day. Moffat and her climbing companions belonged to the second group. Which is the group that gets to enjoy Tower Gap by moonlight, and all those winter bivvies. In a typical aside, an episode barely worth mentioning, a companion (Johnnie Lees, later her second husband) leaves the Pen y Gwyrd Hotel bar "long after midnight to walk along Crib Goch and down to his tent in upper Cwm Glas… it had been a glorious walk: there was verglas on Crib Goch and he had eaten a tin of marmalade."

For a climbing book, there's surprisingly little climbing. In Chapter 9, Moffat's first visit to the Alps involves the Aiguille du Plan in a storm, and an abortive visit to the Tour Rouge bivouac-hut on the Grépon in another storm and lots of fresh wet snow. And that's it – apart from hitch-hiking misadventures, a camp site shared with little pink snakes, a night in a chateau and a nasty encounter with a bergschrund.

In Chapter 8 there is a brief climbing moment; Moffat leads a route on Lliwedd, barefoot and pregnant, to qualify for the women-only Pinnacle Club. Then she spends the later months of pregnancy cleaning and restoring the wreck of an old metal boat. But by the end of the chapter she's persuading a passing hillwalker to keep an eye on week-old baby Sheena while she solos Hope on the Idwal Slabs to join a climb on Holly Tree Wall.

To support herself and the baby, she starts writing outdoor articles for a Naturist magazine at 3 guineas a pop – about £200 today. The magazine would be the oddly named Health & Efficiency, ostensibly a niche magazine for nudists, but actually the one publicly available source of soft-core porn in the 1950s. She illustrates her pieces with photos of herself and companions swimming in Welsh mountain lakes. Soon, though, she moves on to short stories and broadcast talks for the BBC. She finds even more security as she qualifies as Britain's first female mountain guide; meanwhile her writing career continues with 16 books featuring Miss Pink, outdoor type and amateur detective, as she investigates a series of murders taking place in each of the UK's prime climbing areas. In 'Dying for Love', the calm of a sleepy Lake District village is abruptly shattered by an outbreak of murder, kidnapping, blackmail and fatal love. (According to Margaret on Goodreads, "this book is quite awful and I would suggest to anyone who admires Gwen Moffat to steer clear of it.")

Gwen Moffat is usually described as the leading female climber of her generation. In technical terms I'm not sure that she was: she acknowledges Nea Morin and some other members of the all-female Pinnacle Club as being more skilled. But in terms of adventure and Bohemian, bivvybag lifestyle, in terms of total devotion to the mountains, she makes even the likes of Joe Brown and Don Whillans seem – well – just a little bit too tame.

Here's some of Gwen's later writing: