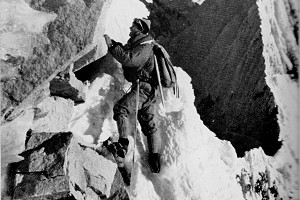

Literature Mountain Literature Classics: Scrambles Amongst the Alps by Edward Whymper

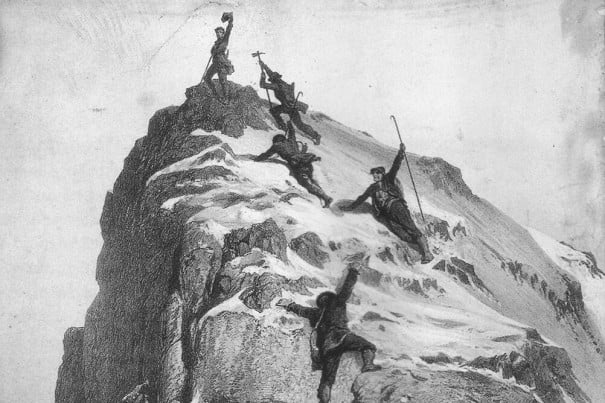

The engravings may be better than the writing, but with its blend of triumph and tragedy, the story of Whymper's five-year campaign for the first ascent of the Matterhorn is one of mountain climbing's defining narratives, says Ronald Turnbull.

Comments

??

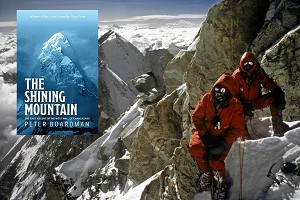

The picture on the cover of the book is fine. Many people including me crawled along the ledge. It's an iconic situation.

the point of this article?

I have no idea what was intended but I found the article thought-provoking in terms of what we might or should mean by 'literature'.

It's tempting to confine 'literature' in a box marked 'Tales recorded through the medium of the written word', but in reality the boundaries of that have been pushed for many decades, as illustrations and photos have been common for a long time, and in 'comic books' the words and images are both integral to the telling of the tale.

The way I see it, we used the word 'literature' when the written word was the only option for published tales, and we've broadened the definition to include images too. Now that we can publish tales through other media, such as audio and video, I don't see a huge difference. Indeed audiobooks are fast becoming the way many of us consume 'literature', so should it really be necessary for a tale to have first been published in print for it to be regarded as literature?

Engagement. Which you've done twice, so it's doing it's job very well indeed!