Literature Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog

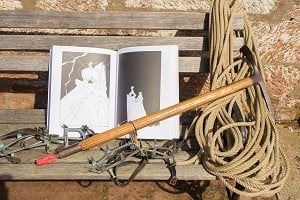

Few have explored the extremes of outdoor life further than Bavarian film-maker Werner Herzog. As well as his many films - some strange, some disturbing - Herzog is a long-distance walker, and a writer too. Of Walking In Ice is only 66 pages, b...

Comments

Great, thanks! Wasn't Wills on the Wetterhorn 1854 not 1844?

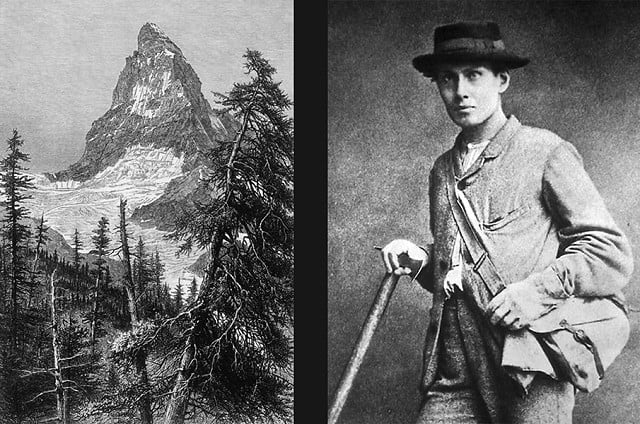

First ascent of the Wetterhorn was 1844 but Will's ascent in 1854 kick-started the Golden era of Alpine first ascents.

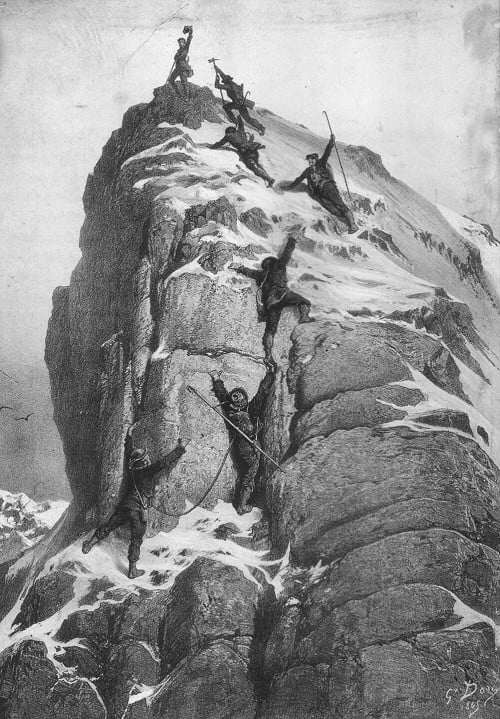

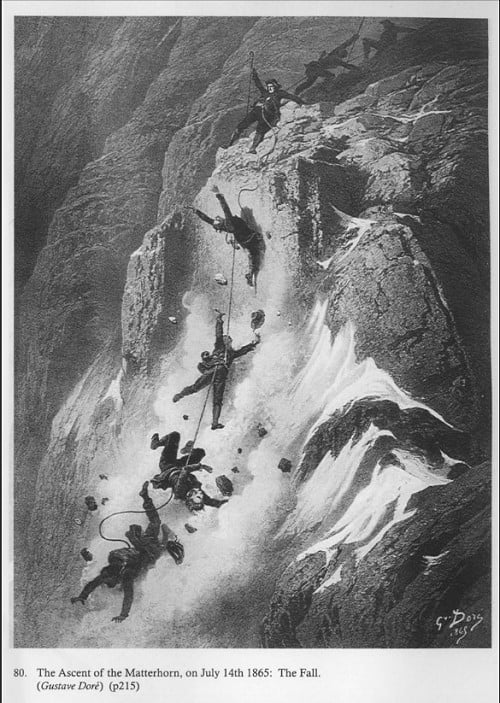

Dates transposed, should read 1865 not 1856 where you first mention Felice Gordano, Ronald.

I'm not really into reading mountaineering books, but I did read this and it's very good.

Thanks, correct both times I think. The Wetterhorn is confusing, it was presented as if a first ascent but the guides had in fact checked it out well beforehand. A bit of class prejudice there along the lines of 'the guides don't count' - prejudice that we don't find in Leslie Stephen and Alfbert Mummery however.

You're welcome. The article's not been updated, so maybe tell UKC?