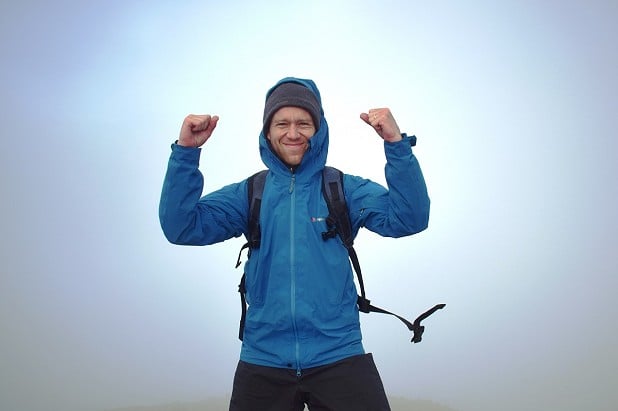

Nicknamed 'Mountain Man' by the Sunday Telegraph, James Forrest climbed all 446 mountains in England and Wales in just six months – the fastest known time. Solo and unsupported, he walked over 1,000 miles and ascended five times the height of Everest. And every step was taken at weekends and on days off work – proving, says James, that it is possible to integrate a very big adventure into your everyday life.

From collapsing tents and storms to near-fatal mountaineering mishaps, James endured his fair share of hardship. But the positives far outweighed the negatives, he told us: he slept wild under the stars, enjoyed fascinating – and often entertaining – encounters and exchanged the 21st-century social-media bubble for a simpler, more peaceful existence. What did he learn along the way? That life can be infinitely more fulfilling when you switch off your phone and climb a mountain.

He told UKHillwalking: "The mountains taught me a simple but transformative lesson too: if you disconnect from technology, you reconnect with something innate and natural. If you turn off your phone and go climb a mountain, life is happier. Priorities realign, everyday worries dissipate, and closeness to nature and landscape is rekindled. Your reality becomes humble, uncomplicated and fulfilling. It is joyous and liberating.

"Every walk I've completed has been time well spent – time for wilderness and solitude, for self-reflection and quiet, for escapism and nature. Every mountain has brought me boundless happiness. Why? Because, in the poetic words of the great fellwalker Alfred Wainwright: 'I was to find ... a spiritual and physical satisfaction in climbing mountains – and a tranquil mind upon reaching their summits, as though I had escaped from the disappointments and unkindnesses of life and emerged above them into a new world, a better world.' I really hope my book inspires others to grab their boots, turn off their phone and go explore that better world."

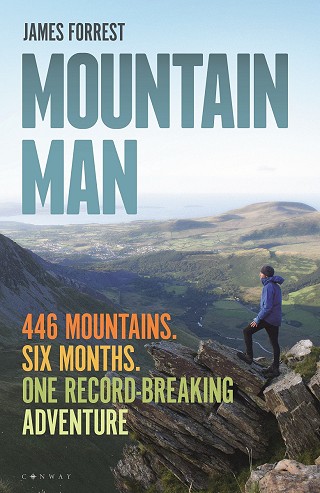

James's peak-bagging adventure – which is recounted in his debut book Mountain Man: 446 Mountains. Six months. One record-breaking adventure, published by Bloomsbury – has been a number 1 bestseller on Amazon in mountaineering categories. Here we exclusively publish an extract from Mountain Man, chapter 11 'The Mind of a Peak-bagger':

By 9pm I had stumbled back down to my car. I was too hungry to bother with cooking anything, so I stuffed my face with a peculiar dinner of chorizo wraps, and peanut butter on Hobnobs. An added oddity was that I couldn't find a knife, so I found myself plastering the crunchy spread on to the nobbly biscuits using my fingers, like a famished toddler let loose in the kitchen. When my hunger was well and truly satisfied, I turned the key in the ignition and drove east as heavy rain began to fall. The forecast had predicted as much and, consequently, I'd booked myself into Hardraw Old Bunkhouse, an independent hostel in the village of Hardraw, just to the north of Hawes.

I checked my phone during my self-imposed 30-minute evening window for internet use and a WhatsApp message from my friend Ed popped up. Our conversation went like this:

Ed: 'How's it going?'

Me: 'All good, buddy. I'm currently in a 30-person bunkhouse in the Yorkshire Dales and I'm the only person here – creepy.'

Ed: 'That's basically the start of every good horror movie – I'll send a search party for you.'

Me: 'Oh God, I think the front door might've just creaked open.'

Ed: 'It was nice knowing you.'

After a fitful night of sleep broken by horror-filmesque nightmares set in a Dales bunkhouse, I woke at 7.30am, ate a breakfast of granola, and prepared for another battle with the fells. My plan was to climb six Nuttalls, combining two of the guidebook's day-walks into one linear route heading roughly north-west from Hardraw to Outhgill, followed by a hitchhike back to the bunkhouse. It was a misty, drizzly day, but it could've been worse. I donned waterproofs and my spare pair of walking boots, opting not to brave yesterday's still-damp pair, and headed through the village to cross Hardraw Beck. I chuckled as I passed a pub with a sign stating 'Hippies Use Backdoor: No Exceptions', weaved my way through fields to the open hillside, and then plodded over pathless moorland to Lovely Seat, my first Nuttall of the day.

As I descended north-west to a minor mountain road on the way to Great Shunner Fell, I contemplated the way my mind worked while out on my own in the mountains. What did I think about all day? Did I substitute internal conversations for human interaction? Was my brain active and alert, solving problems, realigning, de-stressing? Or was I slipping into a state of brain inactivity, like a computer in sleep mode?

It was all of these things and more, I concluded. During my first day of walking after a period of work, my mind would invariably be plagued with worries. Damn, I forgot to post that letter. I must remember to email Richard. I'd better phone Joanne when I'm home. But over time these would dissipate as the therapeutic process of being out in the mountains worked its magic. Work problems no longer seemed so insurmountable; solutions presented themselves; a sense of perspective materialised; and a deeper sense of relaxation kicked in.

This effortless self-reflection went beyond the work arena, too. When out in the mountains, I often found myself thinking about my life in general – my family and friends, my relationships, my hopes and dreams, my mental health – and always seemed to gain a clarity and decisiveness that eluded me in the concrete jungle. Time alone in the mountains was the 'kicking leaves' time I needed to make good life-decisions.

Once I'd overcome the tense mindset of real life, my internal world could go in a number of directions while solo hiking. Sometimes I'd think quite practically, calculating how many Nuttalls or miles or wild camps were left to complete during a trip; or mentally storing information about the walk and the day's experiences, ready to transfer them to my adventure journal that evening. At other times I'd become incredibly inquisitive about something random, wondering about a hiker in the distance (Who is he? Where's he from? Why is he here?) or maybe contemplating the history of the dry-stone wall next to me (When was it built? Who were the men who built it? How did they manage such back-breaking work?). On other occasions my internal dialogue would be entirely haphazard – a long-forgotten memory would surface from my subconscious, or a funny moment from years gone by would pop into my head and make me smile.

When things got monotonous, I might count steps or fence posts, or try to recite the starting eleven of West Bromwich Albion's 2002 promotion-winning team. When I stood atop a clear summit, I tried to identify the mountains I'd already visited and those that lay ahead, envisaging what the rest of my hike would entail. And when I was feeling lonely or tired or fed-up, I thought fondly about my loved-ones and looked forward to the time when we would be reunited. Sometimes, when I'd spent too long alone in the mountains, I'd do strange and disinhibited things, such as loudly mimicking the gargling calls of the ever-present grouse; rapping verses of my favourite hip-hop songs, gesticulating with my hands like a strange fusion of a geeky rambler and Kanye West; or descending into bizarre daydreams about discovering a dead hiker or being attacked by a stag. But, thankfully, I never fully regressed into a state of wilderness-induced insanity. I never once got down on all fours to graze the lush grass with a herd of cows, nor did I ever start talking to the Herdwicks in an attempt to woo the prettiest ewe with my best chat-up lines.

However, more often than any of the thought processes above, I'd simply get into a mindless rhythm of putting one foot in front of the other. I would walk for hours on end, thinking about absolutely nothing at all. I'd get to lunchtime and wonder what on earth I'd thought about for the last four hours – I couldn't recollect a thing. My brain was empty. And in a world where we are all so busy, so preoccupied and so stressed, it was liberating and joyous to feel so vacant.

Even when I was at my most unoccupied, however, the subject of food would always infiltrate my mind. From about 10am I'd obsess about what I was going to have for lunch, where I'd eat it, when I'd eat it and what order I'd eat it in. Two wraps to start with, then raisin-nut mix, then cranberries, then banana chips, and then four – no five – rows of white chocolate. It was a great motivator, a reward to inspire me to complete one last ascent or smash out one more mile. And the food wasn't just about providing sugars and nutrients for my muscles – a good meal always gave me a huge morale boost out in the mountains.

Comments