Ours is a country increasingly divorced from nature, where most of the land remains out of bounds; but pressure to improve public access is gaining political momentum. Eben Myrddin Muse argues it's high time for radical, Scottish-style access reform south of the border.

In England and Wales we have access to just 11% of our land, and within even these limited areas much of what we can do is heavily restricted. Reform is way past due; we should be demanding it.

At the start of 2024, battle lines are being drawn. An invigorated Right To Roam campaign engages in mass trespass across Britain. The BMC and other groups are calling for a commitment to Scottish-style access reform to be introduced to the rest of the UK. There is an election looming, and the country is presented with the likelihood of a Labour Government for the first time in many years. The party has made noises (both good and bad) to show that they're thinking about access reform. This should be a transformative opportunity. But will it prove to be?

Should Labour come to power at the next general election, it would represent the best chance for access reform at Westminster in decades. The last time we were in such a position, our prize was the Countryside Rights of Way (CRoW) act, granted by Tony Blair's resurgent government. It was seen as a popular, cost-effective piece of legislation back then, opening much of our uplands for recreation (more on that later).

Evidence indicates that more access to nature makes us better stewards, better environmentalists

But it's no surprise we're far from satisfied. As a nation, 62% of us now support expanding access rights to the rest of the countryside, even a majority of Conservative voters, and 77% of people aged 18-35 wish they were more connected to nature. Some would have you believe that this desire for more, and better, access is confined to urban liberals, but this is far from the case. A recent Times article reported that 68% of rural voters wished to extend responsible access. Still, there is no shortage of opponents of reform - influential landowner lobby groups cite complaints about land devaluation, littering, environmental damage, and the general ignorance and fundamental indecency of the public.

The BMC, for whom I've been a member, a volunteer, and currently, a staff member, have recently moved to take a more assertive stance on access reform, something I've been really proud of. A decision was made to support a 'responsible right of access' like that enjoyed in Scotland and Scandinavia, where there is a default right to access land and water, and exceptions must be reasonable and justified. It followed a survey of over 4000 members in which 90% supported extending our access rights to most land and water, with only 6% opposing.

I'm not writing this article as part of the BMC access team, although I am that - I'm writing as someone who first became engaged in access issues as a volunteer, speaking with landowners, working with environmental organisations and climbers to protect sensitive sites. I'm writing as someone who's been dragged through hedges and over bogs and hillsides, roughly to the conclusion that the status quo stinks, serving neither nature, nor landowners (who are in this case mostly farmers), nor those of us who wish to enjoy and appreciate all the amazing sights, sounds and feelings that our landscape has to offer, if only we can get to it.

So here we are. Stuck in a state of exclusion - the most nature depleted people on the planet, some of the most disconnected, and allegedly, the least equipped and able to deal with the simple activity of responsibly existing outside of a

town. Apparently incapable of shutting a gate or picking up a crisp wrapper. How do we even begin to tackle this?

Exclusion - Beginnings

In a country where a duke quite recently offered advice to a budding entrepreneur to "make sure they have an ancestor who was a very close friend of William the Conqueror" (who famously divvied up much of England among his cronies) as a guarantee for success, who owns land has long been the fundamental issue when it comes to who can enjoy it.

The right to exclude others has been firmly baked into our laws for nigh on a thousand years. Open field systems without hard boundaries were enclosed into hard squares and manorial estates over centuries. Royal forests and deer parks - a beautiful blight across England - tell a story of how Norman hunting culture displaced people from the land that sustained us; and we're still kept from many of these private hunting grounds, hidden behind high walls. Acts of enclosure from the 12th century not only stripped millions of people of their rights to sustenance, but also ripped people from their connection to the land, tossed to the mercy of the rise and ebb of the economic tide as wage labourers as the industrial revolution churned Britain up. It's a little bit wild to think that until 1832 the sole qualifier in most cases for being able to vote in the United Kingdom was still "do you own land?".

People didn't always leave willingly. Enclosure riots, in opposition to this mass displacement, are considered a pre-eminent form of social protest. Many were even sentenced to death (usually commuted to deportation). In North Wales where I was raised, in 1826 the 140 quarry working families who had built their homes on what was long held to be common land on Mynydd Cilgwyn were told that Lord Newbrough had sought an act of enclosure to secure the mineral rights under their homes.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

They sought legal help and secured the support of the London Welsh and managed to prevent the bill against all odds (they sent their benefactors a home brewed cask of beer as thanks). I was lucky to grow up savouring the fruits of their resistance in the form of a still-preserved common, but this was the exception that proves the rule with some 5,200 enclosure bills between 1603 and 1914 enclosing some 6,800,000 acres in England alone.

Enclosure and the intensification and industrialisation of agriculture was also disastrous for biodiversity in Britain, paving the way for monoculture fields of mass "improved" farmland. The draining of the fens was a particularly egregious offence, with 'Gentleman Adventurers', venture capitalists of the day, led by the Earl of Bedford, draining the marshes to create 'productive' farmland, opposed by the fierce locals known as Fen Tigers who acted to sabotage plans and preserve a way of life dependent on the habitat of the fens.

The "Peasant Poet" John Clare was deeply affected by the enclosure that occurred during his lifetime, a major theme of his work, and once compared it to the devastation of the Napoleonic wars:

Enclosure like a Buonaparte let not a thing remain,

It levelled every bush and tree and levelled every hill

And hung the moles for traitors - though the brook is running still

It runs a sicker brook, cold and chill.

Our land history is a list of fightbacks. From the peasant's revolt against feudalism, to the Diggers' attempts to regain enclosed commons (by literally digging them up and planting crops), there has always been a spirit of resistance in Britain and a folk understanding that closeness and access to nature is good. A concession won by the resistance of this period was (in Wales and England) that acts of enclosure included a record of historic rights of passage on now enclosed land. The many thousand enclosure bills which passed now make up one of most important historical resources for registering historic rights of way and preserving them in the face of modern movements to block them.

As recently as 1940, modern enclosures were dealing death blows to Welsh rural and cultural life - the Epynt clearance, known as "Y Chwalfa" (the destroying) in Welsh, is considered to be the final nail in the coffin of Welsh speaking Breconshire, and is ingrained in our folk memory, as the British army evicted a community to create Wales' largest army training base. They were promised the right to return at the end of the war, with some returning to their empty homes to light fires to keep the damp away or try to plough their fields, only for their homes to be literally exploded to keep them from returning ("We've blown up the farmhouse. You won't need to come here anymore"). One former resident is said to have cried himself to death.

The Romanticism of the 19th century brought a different kind of appreciation of our landscapes that reframed the way society at large felt about rougher moorland and mountain terrain. Far from being the unproductive and dangerous wastes of the past, the poet William Wordsworth and his contemporaries began to popularise walking in nature as an activity in its own right and wrote expressively about their views on the right of people to enjoy it: the countryside to him was "a part of national property in which every man has a right to interest who has an eye to perceive and a heart to enjoy'". Octavia Hill, later a co-founder of the National Trust, saw aesthetic beauty as fulfilling a basic need of humanity, and acted to protect it for future generations. She felt particularly close to the plight of the growing urban demographic of England, driven in their masses to the smoky industrial hubs and effectively banned from the countryside which many of them had left a generation or so earlier.

Our lives are overcrowded, over-excited, over-strained. We all want quiet. We all want beauty. We all need space; unless we have it we cannot reach that sense of quiet in which whispers of better things come to us gently.

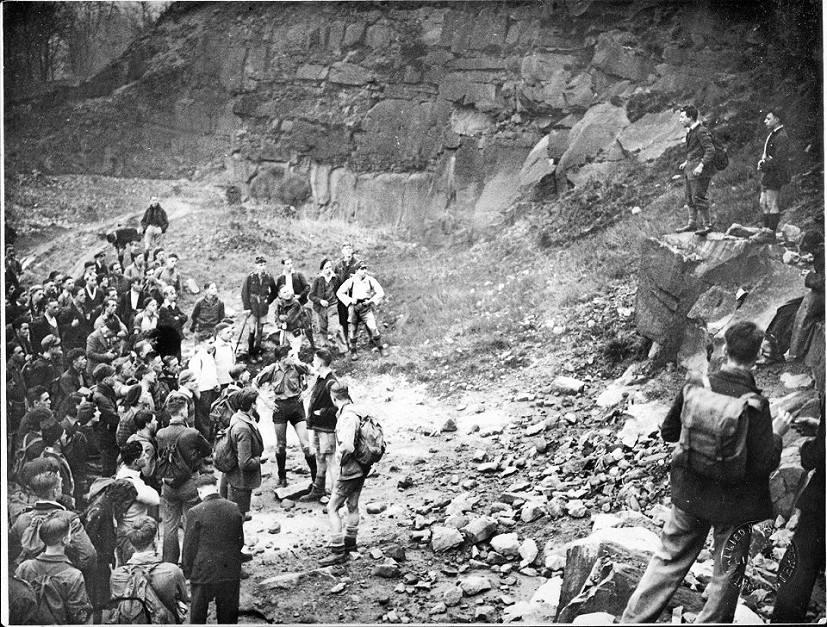

A compulsion for escape was felt by millions, and rambler's groups began to pop up around population hubs. Trespass quickly became the tool of choice for activists as thousands spilled out onto the moorlands only to be rebuffed by genuine threats of violence from gamekeepers in the pay of the large estate owners who preferred to keep the moor for the grouse.

Famed and celebrated is the Kinder Trespass of 1932 - although many such trespasses took place, and rightly so. The grinning communist face of the movement, Benny Rothman, saw access to nature and social justice as one and the same. He also understood the act within its historical context: "It was a demonstration for the rights of ordinary people to walk on land stolen from them in earlier times" he said at the time. "We ramblers, after a hard week's work in smoky towns and cities, go out rambling for relaxation … but we find when we go out the finest rambling country is closed to us, just because certain individuals wish to shoot for ten days a year."

While cities remained smoky and escape difficult, the work of the activists of this time paved the way for the National Parks Act of 1949 led by John Dower. After several decades of failure, the reconstruction period after the Second World War and the desire to reward returning heroes with access to the country they had fought to defend provided ammunition and the political will for genuine reform. Lewis Silkin, a Labour MP who supported the act, called it the following:

"…a people's charter for the open air, for the hikers and the ramblers, for everyone who loves to get out into the open air and enjoy the countryside. Without it they are fettered, deprived of their powers of access and facilities needed to make the holidays enjoyable. With it, the countryside is theirs to preserve, to cherish, to enjoy and to make their own."

The Committee which evaluated the proposals for National Parks - led by Sir Arthur Hobhouse, himself a farmer - returned radical conclusions. First, it backed Dower's recommendation that people should be able to enjoy unrestricted movement over uncultivated land in England and Wales with a process for exemption (not the other way around). Secondly, it suggested that this right should also extend over certain stretches of water. If this had come to pass, we would be living in a drastically different country and many of us would have totally different lives. We were so close! In the end, complications were raised which rang alarm bells for Silkin who by now was Planning Minister, and he began to falter in his support as the reality of the act fell far short of its potential. There are now 13 National Parks in England and Wales. It also notably created the SSSI designation which aims to protect many of our most important habitats.

75 years later, there is concern within the environmental sector that our National Parks fail when measured against key metrics such as quality of habitats, public access, and woodland cover ("the UK's national parks should not be considered "protected areas" unless the way they look after wildlife radically improves" said one report). Within the act there were provisions for path creation and mapping, access orders to grant public access, and powers for the establishment of nature reserves; but it did not unlock the countryside in the way that many had hoped or expected. Campaigners would try again in due course.

CRoW Act

In 1997, Tony Blair swept to victory in an electoral landslide carried on a host of promises. "Things can only get better" he said, and in terms of access to the countryside, things did. As long as you could get to it.

The Government called the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 "The most significant piece of legislation in 50 years and marking the pinnacle of a 116-year campaign by countryside lovers everywhere".

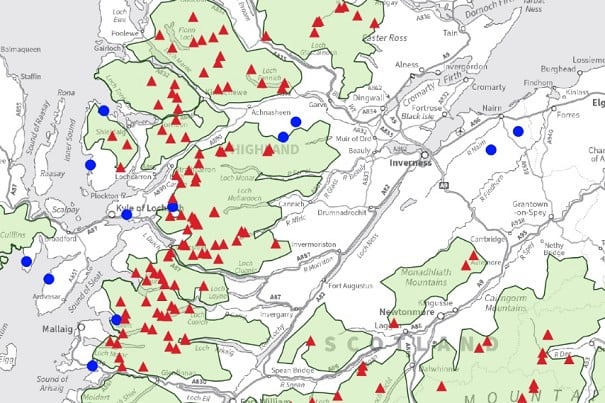

Unfortunately, the early ambition of the bill was rapidly stunted by a parliament divided across class lines, as well as a pre-reform House of Lords then still dominated utterly by the landed gentry (emphasis on landed) who threatened the passing of the bill. The act developed into a plan for a new right of access on foot to a certain type of land, to be dubbed 'open access land' and marked in yellow-orange colour on your OS map. Open access land comprises mountain (over 600m), moorland, heath, downland, and registered common land. Targeting 'open country', it does not include watersides, woodland, or other types of grassland. Including woodland alone would have doubled the coverage of the act in England. The act specifically allows climbing (thanks to BMC lobbying at the time), running, birdwatching, and picnicking, for example, but cycling, bathing, boating, organised games, and other activities are not covered. Many major areas simply fell through the net - Vixen Tor on Dartmoor being one infamous example.

CRoW's 'partialist' approach to access where one field is defined as 'open country' and the next as improved grassland is not one based on innate physical properties of the land, which typically refuses to obey the lines on the map and evolves with use, and the passage of time. When I was walking recently in Cwm Cynfal near Ffestiniog, I passed through a dry-stone wall which formed the boundary between a private field where I was legally obliged stay on the path (unmarked) and open country where I could climb the nearest rock or lay down for a picnic if I felt like it. It felt arbitrary and weird, an experience echoed by the Right to Roam mass trespasses along the Scottish border where the law feels arbitrary and nonsensical.

The act of mapping out all of Wales and England into 'access land' and otherwise was a monumentally slow and expensive undertaking, with long drawn-out disputes. It carved out the uplands and left much of lowland Britain (where most people actually live) far removed from its potential. In the Peak District, 72% of the land is 'access land', while in Kent that number is a fairly stark 0.6%. It's little wonder that in our National Parks there is a perception of 'the great unwashed' stomping across the moors like a mad stampede - under our current regime of access they simply have nowhere else to go, and they face many barriers in order to get there in the first place, leading to a more affluent, whiter, population engaged in outdoor recreation.

The access needs of most of the country are served by a disparate scatter of old commons, wastes, and access islands (expertly documented by Instagram account Private Britain). To me, access islands represent the worst aspects of CRoW. Impractical, illogical, indulgent, and particular to the extreme; oases of open country, free for our leisure as a nation (and counted in that 11% access stat) but requiring trespass or parachute to approach. They are an inevitable consequence of a default of exclusion over the default of access and a pure contradiction.

There are 92 constituencies in England with no access land whatsoever. But those people are all served by our cherished path network, right? Right?!

Paths to Prosperity

We enjoy 140,000 miles of paths in England and Wales - a significant network which dwarfs that enjoyed by most of our neighbours. These paths are the legacy of millions of lives lived across the land over millennia: Roman roads; drovers' roads over which livestock were taken to market; or ancient raised trackways like the Icknield Way following natural features of the landscape. Unfortunately, campaigners say that many of our historic paths are at risk of being lost forever.

Our history of access reform is a stepwise journey towards land justice. The opportunities are vast, and the risks of inaction significant

CRoW was also responsible for the introduction of a deadline for registering historic rights of way in England and Wales - January 1st, 2026. It was supposed to provide clarity for landowners although the legitimacy of this claim has always been disputed and the deadline has now been extended to 2031. Since the act passed, councils have been ill-equipped to deal with the process of registering these paths - the Ramblers (who provide an excellent guide on how to record historic rights of way in your area) say that despite having 600 volunteers researching these rights of way, there are still over 40,000 miles of paths missing from the map in England alone. The Welsh Government has promised to repeal, but lacks the political will to do so, preferring to delay and dither, and pass ing the responsibility for access from minister to minister like a hot potato.

Kate Ashbrook of the Open Spaces Society summed it up as follows:

"It is excellent that the Welsh Government has for some time expressed its intention to repeal the 2026 cut-off for recording historic routes on the definitive maps, but it does need to get on and do this. Until it does, this pernicious cut-off hangs over us and we need to claim historic routes before they are lost. The Westminster government has done the opposite, bringing the cut-off effect, albeit set back to 2031, and it has done so before introducing the regulations for the exceptions from the cu e evidence for them comes to light."

All access organisations are calling for this cut-off to be dismissed, but the cliff edge remains as we hurtle along towards it. As with access reform in general, there is no champion willing to take it forward.

There's no doubt that our rights of way network is a vast and impressive vascular wonder but with a BBC report claiming that our paths are blocked in 32,000 places, it couldn't be described as being in rude health.

For historical reasons (related to enclosure, mentioned above), Scotland has never enjoyed a path network anywhere near as great as England and Wales, but for those paths that do exist, the right to roam has supercharged their utility, as well as enabling the creation of new paths. For landowners, paths are the best tool available for managing access on land. A default of access, augmented by a robust support for path repair, stiles, and gates means that nobody needs to hop a fence or climb a gate.

People love paths and try to stick to them as a rule when going between places, but many of us want to use them to go places. Off the beaten track is a wonderful phrase. I want to use them to see the parts of Wales and England that I've been kept out of. I want to use them to go to crags or to swim in beautiful rivers or ponds - the capillary action to bring the true potential of these paths to every community. Inclusivity campaigner and data scientist Andrew Wang has used data from Strava to map public rights of way and trespass, noting that many paths of interest are not registered rights of way, either being unofficial, or historic rights of way that are awaiting deliberation.

A CLA (Country Land and Business Association) spokesperson recently said "nobody is forced to trespass", a statement which is at the same time both true and absolutely meaningless. Nobody's 'forced' to trespass, true, but nobody's forced to pay the rent, to brush their teeth, to eat. All are basic requirements for existing these days, and for many of us trespass is no different. One could also say that nobody is forced to exclude others from their land without good reason!

What's the situation in Scotland?

In Scotland things function far better. The Scottish Land Reform Act took two years to implement, compared to five for CRoW, with no need for complex mapping, and its legacy, 20 years later, is astonishing. The LRA provided legal clarity for landowners, with the firm principle of "take responsibility for your own actions" forming a key tenet of the Scottish Outdoor Code.

The act and the culture it has beckoned in is a point of pride, enjoying support from not just 81% of the general public, but also organisations which had opposed the act at the time of its proposal such as the farming unions.

At a debate at Kendal Mountain Film Festival in November, a panellist from a Scottish inclusive walking group was asked something along the lines of "so you have a right to roam in Scotland - but it's not all sunshine and rainbows, right?" to which she responded quite literally with a smile and a chuckle, saying that "no, actually, it's pretty great!" and it struck me just how beloved this right is. I've been lucky enough to enjoy it myself over the years and there is something to be said for the simplicity of a policy which tells you, yes - you have a right to be here; have fun but do no harm. While public use of the countryside in Scotland is not without issues - dog bothering, for example, remains a problem here as everywhere - an impressive 92% of Scottish survey respondents claimed to have experienced no access issues within the last 12 months. Land prices in Scotland have continued to rise in direct contradiction to some wild claims at the time of the act's debate. There has been no obvious relationship between access and rural crime (although some have theorised that having more 'eyes on the ground' may actually help discourage activities such as fly tipping - we have certainly found this to be the case at crags visited by climbers).

Many will say that the Scottish landscape is of a completely different flavour to that of England or even Wales, but is this really relevant? Most people - wherever they live in Britain - are urban. A Norwegian once remarked to a friend of mine when asked where their right to roam began - "why, as soon as you leave the city", and this is as true in the densely populated urban fringe of Scotland as it would be in industrial South Wales or the commuter belt of England. There seems no innate issue with applying a right to roam to areas near where people live - in fact, you could argue that this is where it's needed most.

I have surreal memories of catching the train to Glasgow as an 18-year-old, setting off on the West Highland Way from the middle of town, and immediately finding the freedom to pitch up sensibly in a quiet spot. Quite literally a complete perspective shift for a boy who grew up in the foothills of Wales' biggest national park, where I had never wild camped, not even once. In Scotland, they have used powers within the act to establish additional core paths around urban areas, to manage and promote access. It would be no different in Wales or England, other than the paths are already there!

The Scottish Land Reform Act was designed to convert long standing customary freedoms into statutory rights, and Dave Morris, former Director of Ramblers Scotland, said it best:

"A freedom needs to be converted into a right when that freedom is being subject to erosion"

We've been experiencing this erosion in England and Wales for a very long time with micro enclosures and the removal of rights of way. The Open Spaces Society is constantly campaigning against the threatened loss of our remaining tracts of common land and green spaces. If we don't act to protect the access we have, or better yet, enhance it as has been the case in Scotland, then we risk the continuation of a shifting baseline for access, robbing future generations.

'Stampede'

You wouldn't expect someone to walk without being able to run, and so I wonder why there is such an expectation on first-time visitors to the countryside to be properly equipped for the experience, to become model tourists from scratch. The government have simply been negligent in their responsibilities - formerly spending only £2000 a year on promoting the countryside code (and all of that allegedly on printing costs).

Our current regime of exclusion cheats no-one as much as it cheats those who live in a sad, empty countryside and an ill-equipped population of visitors who pass through the land without understanding or interaction

Landowner lobbyists such as the Countryside Landowner Association have called for it to enter the natural curriculum and I agree, it's just that our dull, prohibitive code compares so poorly with its contemporaries. In Norway and Sweden, they have a deeply entrenched culture of "don't disturb, don't destroy" baked into the way they interact with the countryside, known as "Allemansrätten" (every person's right). There's a beauty, a pride and romance to it. In Finland they emphasise that despite having the right to access 96% of their country, they should enjoy it as they would as a guest in another person's home, i.e. don't trash the place. It works! In Scotland similar principles apply, since the Scottish Outdoor Access Code (it's even named more positively than the countryside code) explains your responsibilities as well as your rights.

Regardless of a code and its promotion if, like me, you have to travel ten miles or more to your nearest patch of 'access land' where you're legally allowed to step off the path, it's probably difficult to build an understanding of what access land is and what you should do with it. The onboarding process of bringing people into contact with nature is stunted and over-complicated. It's the default of exclusion, and unfortunately CRoW is partly to blame. The evidence indicates that more access to nature makes us better stewards, better environmentalists. The same innate desire to experience beauty, to be connected and to perceive our shared landscapes drives the so called 'bucket and spade brigade' up the Watkin Path on Yr Wyddfa as drives a climber or a fell runner on a lonely peak on the other side of the valley. Octavia Hill knew it. I've seen land managers and public bodies fall too easily to snobbishness and elitism when speaking about the 'great unwashed' (we have so much terminology dedicated to stomping people down). The fact we all share this need to be in nature is actually a good thing.

Our leading educators for the outdoors, running mountain qualifications, are being squeezed by a landowning fraternity that is increasingly hostile to their activities. Many in North Wales have had to stoop to paying landowners to 'wild camp' on their hillsides. Duke of Edinburgh award candidates are similarly made to sneak around under the radar - and these are supposed to be exemplary qualifications to educate the next generation of outdoors enthusiasts.

Wild camping is one of many ways we can connect with nature - it's a solitary and beautiful experience - yet completely banned everywhere in England and Wales but Dartmoor. And even there, that right has been repeatedly challenged in court in recent times.

The citizen scientist movement is another component of a more access-friendly world promoting an interest and passion for nature. Surfers Against Sewage, Trash Free Trails, Protect Our Winters, and Tidy Climbers are all organisations born from access to nature, to look after it and reduce our impact. Trash Free Trails' founder points out in The Book of Trespass that the slogan 'Keep Britain Tidy' is redundant. The countryside is already packed with litter and it's not because we already have access to so much of it! Campaigners are leading the way on holding landowners and industry polluters to account. From the dying River Wye to the crap-drizzled beaches all over Britain, we need more eyes on nature than ever before.

Greater land access and education absolutely need to go hand-in-hand for the trend to be sustainable, but improving public access to the outdoors has a lot of benefits that I believe outweigh the costs. A sense of ownership can lead to greater respect for the land and an awareness of responsibility, and more public spaces create further opportunities for organisations to provide crucial education - and indeed, to exist in the first place.

The American naturalist Robert Pyle wrote: "What is the extinction of a condor to a child who has never seen a wren?," a remark more relevant than ever in an age of shifting baselines and biodiversity collapse. There are 73,000,000 fewer birds in Britain now than there were in 1970 and that's not due to the passing of CRoW. That's a lot of wrens we're not seeing any more.

If you live in the Lakes, North Wales, or the Peak District, you may feel slightly removed from those calling for access reform. Paths in national parks are more likely to be well used and blockage-free. But not everyone can be so lucky. Many feel able to enjoy a sneaky evening wild camping without being troubled, yet many others will be prevented by the barriers in place, non-physical though they are. Women, in particular, are far less likely to break a rule even if they disagree with it. Besides, even in places where camping has been an assumed right for decades, recent events suggest that without explicit legal protection, such rights are fragile.

Whether we choose to admit it or not, much of our experience as climbers and walkers is built on trespass. Sometimes things progress to permissive agreements, but quite often our access is snatched away with no justification besides "it's my land and I don't want you there" and we are without recourse. Speaking as a BMC staff member, when there is environmental concern, or disruption to the landowner, you can have a conversation, but only if the landowner wants to talk - and no one is obliged to.

On Rural Life

Many have claimed to be the true voice of rural Britain over the years, from landowner lobby groups to recreational shooting groups posing as conservation charities. I make no such claim, although I grew up in about as rural a place as you could imagine, stepping over more sheep shit in my formative years than you might ever believe. What I can do is talk about my experience of the countryside growing up. A school, two corner shops, a post office, a bakery, all gone from my village during my lifetime. The wider area is full of adfeilion (ruins), left from an era when the countryside was more populous. I've often imagined how it would have felt to live in a village that could actually fill the many derelict chapels that scattered the landscape; one where the school had more than 30 children, where the carnival wasn't cancelled for lack of attendance.

The mass abandonment of the countryside has been disastrous for country life. It's caused an epidemic of loneliness and mental ill-health among the farming community, and indeed many feel that mental health is the biggest problem in agriculture. I grew up in the farming community - my Welsh ancestors are all farmers going back as far as records exist and I was a keen member of the Dyffryn Nantlle Young Farmers Club growing up (nobody parties like a young farmer). My background matters because it's what makes me so certain that our current regime of exclusion cheats no-one as much as it cheats those who live in a sad, empty countryside, and an ill-equipped population of visitors who pass through the land without understanding or interaction. Changing how we interact with the land, with nature, with the people who work the land is a part of the solution.

Our society demands so much of our land managers, so many of whom are farmers (and in Wales, predominantly smallholding farmers). They are on the frontline of the climate crisis, the nature crisis, asked to sequester carbon and be conservationists on top of their primary duty to feed us all. And currently, they are completely and utterly unsupported even if they desire to manage their land positively for access (or nature, for that matter). That needs to change. In Wales, the current iteration of farm support payments, the sustainable farming scheme, risks falling far short of its potential in changing the game.

Many farmers are already thinking ahead - through initiatives such as campwild some are facilitating near-wild-camping experiences, others sticking with an old-fashioned field and honesty box for camping or parking. In Fairhead near Ballycastle in Northern Ireland, the landowner has reached near legendary levels of love and appreciation from the climbing community for his efforts in facilitating and welcoming access to the famous cliffs on his farm (Sean McBride, we love you). When I went there, I was overwhelmed by his generosity of spirit and shared love for that spectacular area. If climbers were to abuse his trust, they would certainly become pariahs.

After Covid, Glamping pods provided a much-needed boost to many farmers' incomes and increased their resilience. Greater access benefits these diversifications. Speaking for myself - I'm much more likely to come stay in your bell tent with a jacuzzi and log burning stove if there are some boulders nearby that I can confidently go and climb, or a creek to dip in. Recent research shows that the present contribution and potential future economic benefits for rural communities in increasing access to nature and outdoor activities are simply massive - good quality jobs in rural areas.

There are matters on which access campaigners and farming unions may continue to clash, but we also agree on some things. Livestock worrying by dogs for example is often thrown at me as an example of an unfixable problem that access would only make worse. It's hard to look at a dog the same way if you've witnessed the result of an attack on livestock - they can be truly destructive and heartbreaking. But there are measures that can be taken to address this issue. Scotland has recently increased the fine for dog worrying from £1,000 to up to £40,000 and imprisonment, and there is certainly room for discussions on mandating leashes or excluding dogs entirely from sensitive areas.

The Future

So the opportunities presented by real, meaningful access reform are vast, and the risks of inaction are significant, with shrinking biodiversity, blocked paths, and micro enclosures everywhere.

Our history of access reform is a stepwise journey towards land justice for all of us. As outdoors enthusiasts we have a responsibility to both be aware of our current state of exclusion, and to be genuine advocates for those who have not been given the chance to develop the love we have for our environments and the access we've enjoyed. We are the lucky ones - but we need not be.

The law is nonsensical, arbitrary, and overly complex; we should be advocating for clarity of purpose, without complex and bureaucratic mapping which serves nobody and confuses everybody. If you happen to be a legislator reading this, then it's time to pull your finger out and put some time and resources into genuinely looking at access reform as a mechanism for social justice.

What can you do?

For anybody interested in learning more about our history and the potential future of access, there is a significant body of work which has informed much of this article, and I owe the authors a debt of gratitude - from Marion Shoard's seminal text "Right to Roam" which lays out the historical context for where we are right up until the passing of CRoW, to the excellent Book of Trespass/Trespasser's Companion by Nick Hayes which sets out so many great arguments for reform.

We're lucky to be living in a time when momentum is gathering around access reform. The Right to Roam campaign has exploded to more than 50,000 followers in just a few years. The BMC's Access Land Film shot to be our most liked post ever, and most viewed reel on Instagram within two days. I hope you feel driven to add your weight to the campaign. It needs leaders and activists from all backgrounds, all over England and Wales. And if you don't feel like going as far as the wholesale export of 'the Scottish Model,' then maybe press for our own adaptation of Allemansrätten (if you can think of a catchy Welsh version please get in touch) or a way of bringing us to nature that's of our own making - a way for us all to better share this amazing land of ours, more fairly, more compassionately, and (yes) more responsibly.

Find out more

These are some books that I've found really helpful in better understanding the subject:

- A Natural History of the Hedgerow by Jon Wright

- Who Owns England by Guy Shrubsole

- The Book of Trespass and The Trespasser's Companion, both by Nick Hayes

- A Right to Roam by Marion Shoard

- Shaping the Wild by David Elias

- Walking Class Heroes (Pioneers of the Right to Roam) by Roly Smith

- Reconnection by Miles Richardson

- Local by Al Humphreys

Glossary

Public right of way (PRoW): A legal right of the public to pass and repass on a specific path. These paths are typically marked with signs or coloured arrows. PRoWs are an important part of the UK's landscape and heritage, and they provide a valuable resource for recreation and access to the countryside.

Open Access Land: Identified on OS maps as a yellow (inland) or magenta (coastal) wash, you can walk freely, climb, run, explore, have a picnic, but you may not cycle, swim, camp, use a metal detector. 11% of England and Wales is designated as open access land.

Allemansrätten: Meaning "Everyman's Right" in Swedish, this is the unique tradition of public access to nature in Sweden, allowing anyone to walk, cycle, ride, ski and camp on most land, excluding cultivated areas, houses and private gardens. It is conditional based on the responsibility not to disturb or destroy, not to leave any trace, and to be considerate of others and their property.

CRoW Act: This grants public access to specific types of land in England and Wales, known as "open access land." This includes mountains, moorland, heaths, some downland, and commons. People can walk, run, have a picnic or birdwatch, but activities like horse riding, cycling, swimming, and camping are restricted.

National Parks Act: This act established designated areas as National Parks and set out regulations for their management, conservation, and public access. They grant limited access rights within the park boundaries, often focused on public footpaths and designated trails.

Acts of Enclosure: Historic acts of Parliament, mainly in the 18th and 19th centuries, that privatised previously common land used and often lived on by communities.

Right to Roam: Understood to be the campaign for legislation that grants public access to more land for activities like walking, cycling, and camping. It is also the name of a popular campaign group.

Trespass: Entering someone's land without their permission is considered trespass. This can occur even on open access land if you enter restricted areas or violate specific regulations. It is important to be aware of local rules and signage to avoid trespassing. Simple trespass of the kind usually enjoyed by walkers and climbers is a civil offence, meaning it doesn't incur criminal penalties, however there are nuances to consider - some circumstances can elevate trespass to a criminal offence (known as aggravated trespass), such as remaining on land after being asked to leave, causing damage, or trespassing on designated protected sites such as military bases.

Historic rights of way: Public rights of way that existed before 1949 but were not recorded on the official maps maintained by the local authorities.

Comments

The single biggest theft act in British history were the Enclosures Acts, first in Elizabethan times and the in the 18th century. I can distinctly recall starting my grammar school history O Level (Social & Economic) with this topic. The word was unfamiliar and little did I realise at the time what this represented. It was masked at the time as a better method of farming, rather than the Strip farming of Feudal times. But this single act, precipitated by the landowners in Parliament was legalised theft. Overnight the English common vanished. Sheep had to be enclosed although they had managed to prosper quite well before that. Even the tops of mountains were traversed by walls and barbed wire.

The nations largest landowners today mostly acquired their land and subsequently even more wealth in this legalised robbery.

However this debate is not all one-sided. Last year I revisited Dovedale, a frequent climbing venue when I lived around Manchester. I was appalled at the vast quantities of litter left by the present generation that has apparently little respect for our countryside. Pizza boxes were pile six deep. Visitors had picnic Ed and left black bin-liners of rubbish in piles, that is the few that could be a least a little bothered. The river was a cesspool. It was totally depressing. And let us remember this is a premier "beauty spot". I've seen less litter in the back streets and 'cricks' of Handsworth (B'ham). On the plus side I must admit that the summits of both Yr Wyffda and Scafell Pike were remarkably litter free, excepting for the odd banana skin festering in some crevice. So if we want to reclaim the countryside we have to get our own house in order first.

Thanks for writing a very well considered and researched article. We have a 'mountain 'to climb' as far a access is concerned, and if improving land by covering it in cattle-shit is a symptom of the fight ahead, it not be easy.

A good, detailed article.

Perhaps the BMC should join forces with the Ramblers and others to fund some Parliamentary lobbying.

Excellent article, that raises many interesting points.

Regarding the financial benefits of good access - we rented a house on a farm in Devon for a week last year, and specifically rejected several areas where there was poor access to the countryside.

Stuff like this:

https://www.thebmc.co.uk/outdoors-for-all-prime-minister

And these:

https://www.thebmc.co.uk/outdoors-for-all-a-manifesto-for-the-outdoor-sector

https://www.thebmc.co.uk/nature-2030-campaign-launched--people-and-nature

https://www.thebmc.co.uk/the-future-of-access-rights

It sounded like the BMC was making some great headway last year, particularly with Labour, unfortunately the whole "green backlash" and climate scepticism within the Tory party took hold again after the Uxbridge by-election and Labour got frightened off pushing on anything which looked too environmentally focused.

Thanks Eben.

One big issue you overlook is how busy traffic on roads has reduced our effective access in modern times. Too often these have become almost 'no go areas' for much slow traffic (be that pedestrian, horse, bike or wheelchair). I believe we could make massive improvements if we had multi-use pavements or parallel link paths where footpaths or bridleways end at such roads, to link to the next path away from the busy road. Small changes could make a massive difference to the utility of some of our path network.