Tents and fire don't mix... or can they? With a change in philosophy from fast and light to slow and luxurious, it's possible to enjoy secluded spots in warmth and comfort. As the long cold nights of winter approach, John Burns (let's hope it's not a case of nominative determinism) explains what the Hot Tent is, and why he's found it a revelation.

What memories come to mind when you think of camping in the winter? Do you see bright crisp days with sparkling snow beyond the door of your tent? Do you imagine yourself lying snug in your sleeping bag whilst all around you is frozen? More likely you have some less pleasant recollections. Perhaps you can remember shivering in the dark depths of a Highland winter's night as the long hours of darkness crept slowly passed. Or you may picture your tent being buffeted by endless wind and rain while you are engaged in a continuous fight to keep your shelter and all your possessions from sinking below the water level.

If your memories of camping in winter are of an unpleasant nature you may be pleased to know that there is a new kind of camping, which involves none of the suffering traditionally entailed in using a small nylon tent. When it comes to comfort, light and fast will only get you so far; in some respects heavy and slow can be so much better. The revolution in camping has come with the development of the Hot Tent. For those who've never heard of one, this is a heavy canvas tent, often a bell tent, with a woodburning stove at its heart. Yes, you read that right.

Many years ago, I watched in horror as a tent in the campsite at Langdale burst into flames. Its owner had left a Primus stove lit in the tent while he went over to the toilet block. Petrol stoves are evil little things, and this one, realising it was unsupervised, took the opportunity to flare up. Three minutes later the owner of the tent returned to discover that all that was left of his canvas and possessions was a smouldering rectangle of burnt grass. The lesson that fire and tents don't mix has been etched in my memory from that day on.

It was a revelation: I was warm, I was comfortable, and most important of all, I wasn't on fire...

Sitting in my newly acquired hot tent one dark December night it was with some trepidation that I reached into the open door of the stainless-steel stove and touched the kindling with a match. I was far from convinced that I wouldn't suffer a similar fate to the Lake District camper all those year ago. As the kindling caught light, bright yellow flames began to dance in the heart of the stove. I closed the steel door and waited, knowing that once the stove was lit there was no going back. A rumble emanated from the belly of the stove as the logs caught fire and the steel box became a living thing. Soon heat filled the tent. It was a revelation; I was warm, I was comfortable, and most important of all, I wasn't on fire.

That first night I was even more surprised when I left the tent wearing only a T-shirt and jeans to discover that outside its warm refuge the Highland night had plummeted below zero and the ground surrounding my tent was sparkling with hoar frost, and frozen solid.

Although the use of these type of tents in British camping is relatively new the Hot Tent is in fact an adaptation of a very old idea. The tent I use is Scandinavian in origin and has been adapted from designs used by the nomadic peoples of northern Europe.

It may sound like heresy to the lightweight brigade, but despite its weight the Hot Tent has given me a new freedom

Apart from its comfort, something a man of advancing years like myself is very grateful for, the Hot Tent has other major advantages. Anyone who has camped in wet conditions in a lightweight nylon tent will know that no matter what you do to try to prevent it, eventually the wet gets in. Unless you have the chance to get yourself dry you inevitably carry moisture into the tent every time you enter from the rain. The result is a kind of soggy sensation that slowly robs you of any comfort and warmth. Over time this dampness will gradually affect your ability to function and may even threaten your safety. The great advantage of the hot tent is, not only is it virtually impenetrable to rain, but there is enough room to hang your clothes up near the stove and allow its heat to dry both you and everything else. This means that by the morning you will have dry clothes to wear, and your sleeping bag will also have been saved from the steady onslaught of moisture.

You may have already worked out that a Hot Tent with a stove in it can in no way to be described as lightweight camping. Hot Tents are the heavyweights of the camping world. Mine weighs around 16kg, the stove a few kilogrammes more. This means that hauling it more than a few yards from the road is not easy. This is not the kind of tent that you will throw into a rucksack and carry across the hills for days at a time.

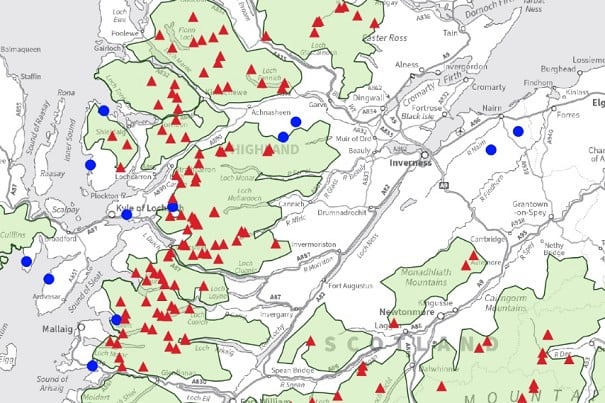

Despite the disadvantages it has in weight I have found that the Hot Tent has given me a new freedom. In the days when I only visited highland bothies I could only go to places where a bothy existed. This obviously limited me. Now I'm able to go to remote parts of the Highlands and use the tent as a base camp for my walking activities, knowing that at the end of the day I will have somewhere warm and comfortable to relax and recover.

My set-up cost me around £3,000, so a Hot Tent is far from cheap. That might sound a lot of money but when you consider that a Hot Tent offers much the same facilities as a camper van, it begins to look inexpensive.

For decades in the UK manufacturers have striven to produce lighter and lighter tents and hill goers have fought to reduce the weight of their portable shelters. To the devotees of these minimalist shelters the Hot Tent will sound like heresy. Even more so when I reveal I cover the floor with carpet and light the tent with a brass paraffin lamp while I sit in a folding armchair in my carpet slippers. Bivi bag owners from across the nation will be rising up in indignation as they read these words.

I ask only that you pause for a moment before you erect an aluminium scaffold and rig up a nylon noose. Consider this: I mostly use my Hot Tent in the winter months, in the remoter parts of the Highlands. I am in my late sixties and, as a gentleman of advancing years, the thought of spending long nights in the confines of a nylon backpacking tent fills me with dread. The Hot Tent allows me to enjoy going to places in winter that would otherwise be impractical. I'm conscious of the fact that access to our wild places is often controversial and, as a result, I am always very careful to minimise my impact. To me, my canvas tent with its chimney is far less obtrusive on the landscape than the alien shape of a large vehicle parked overnight. I take a pride in following the Leave No Trace philosophy, leaving only a flattened patch of grass to mark my passing.

A Hot Tent will not be to everyone's taste but for me it represents an exciting new way of spending my days, and some of my nights, enjoying a remote camp with the smoke from my stove mingling with the starlight.

The Hot Tent Diaries

John Burn's new book The Hot Tent Dairies follows on from his series of bestselling outdoor books which include Bothy Tales and The Last Hillwalker.

As well as sharing the author's adventures there is practical advice on setting up a hot tent and some suggestions for little-known camping spots in the heart of the Highlands. The Hot Tent Diaries are a great introduction for anyone who wants to follow John into the wild – an invitation to adventure.

Available as a single volume in paperback from Amazon and the Fort William Bookshop, it can also be purchased as three short e-books.

- OPINION: It's The End of An Era For Cairngorm Bothies - And The Start of a New One 22 Oct, 2023

- PODCAST: Lyme Disease - What You Need to Know 12 May, 2022

- Desert Island Peaks: John Burns 14 Jan, 2021

- 10 Tips For a Winter Bothy Night 20 Dec, 2019

- Eight Things They Never Told You About Mountain Navigation 2 Aug, 2018

- OPINION: Are Bothies Being Commercialised to Death? 19 Mar, 2018

- Ten Things They Never Told You About Hillwalking 16 Nov, 2017

- 40 Years On The Pennine Way 21 Sep, 2017

- GEAR NEWS: The Last Hillwalker, by John Burns 22 Aug, 2017

- 10 Types of People You'll Meet on the Summit 9 Aug, 2017

Comments

Looks like a glamping pod.

The comfort must surely be tempered by the discomfort of having to actually carry the thing 'to remote places'?

I don’t think anyone carries them to remote places. I guess traditionally they would be hauled or pulled by dogs, but these days they are mostly shifted by pick-ups. They may have Northern European origins, but modern hot-tents are very much the domain of Americans with a collection of knives and axes.

As the article says, the author uses his as a basecamp to which he initially drives, and from which he can then do day trips.

But as the first sentence of the article says:

With a switch from fast and light to slow and luxurious, it's possible to enjoy remote places in warmth and comfort.

Don't shoot me - I'm only replying to the words that have been written!