There's far more to peat than wet feet. From climate change and flood management to wildlife habitat, the humble blanket bog has a huge role to play, says Lyndon Marquis - and it's up to us hillwalkers to look after it.

If you've spent any time walking in the uplands of Britain, then you've almost certainly encountered (and possibly cursed) blanket bog. The going is getting squelchy, the path gradually turns into a deep, black gutter perhaps two metres wide and one metre deep, and the distance you'd measured on the map is doubling as you sweep out through clinging green pools to keep the right of way in sight without actually using it. So what is blanket bog, and why should you care?

According to the IUCN UK Peatland Programme, blanket bog "Typically occurs in the uplands as mantles of peat over extensive areas[…]. Healthy blanket bog is mainly composed of bog vegetation fed only by precipitation and is consequently nutrient poor and acidic."

In simple terms, blanket bog is peatland occurring in the uplands (in England, anyway; you can find it at sea level in northern Scotland). Peat forms from the remains of plants in waterlogged, acidic conditions. Because it doesn't rot (or does so very, very slowly) the layers of peat build up and can be very deep. In fact, peat typically only accumulates at around 1mm every year so 1m of peat can take up to 1000 years to form. Some of our peatlands in the UK are up to 12 metres deep and so these ecosystems can be really old. I should point out that the deepest peatlands are lowland habitats so you're not going to find any of those while you're summit-bagging.

Sphagnum mosses are the keystone species for peat formation. Once established, they make their surroundings wetter and more acidic, so perpetuating both their own favoured conditions and those for peat formation. You'll find other plants – cotton-grasses, crowberry, bilberry, sundews and such – but Sphagnum is the habitat architect.

Peatlands are the world's largest terrestrial carbon store. They cover around 10% of the UK's surface and yet store more carbon than all the forests of the UK, France and Germany combined

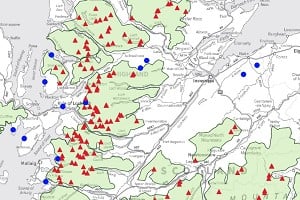

The UK is one of the world's top ten countries in terms of peatland area, with 2 million hectares of it – space enough to hold 1.6 million cricket matches at once. So our peat bogs are globally important, with as much as 13% of the world's blanket bog formed in the cool, wet climate found here. 60% of the UK's bog habitat is in Scotland and around 14% is in England.

The majority of England's blanket bog is found in the Pennines, with other significant areas in Dartmoor and Exmoor. Yorkshire Wildlife Trust estimates that there's around 70,000 hectares of blanket bog across the Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors National Parks and Nidderdale AONB. At an average depth of 1.01 metres, that's 707 million cubic metres of peat.

And how does that impact upon walkers like you and me (apart from it being in our way)? I've spent most of my adult life scurrying, traipsing, trudging and, on occasion, wading in the uplands of North Yorkshire – more so in the Dales than the North York Moors. So I'm going to take a look at three peaks in Yorkshire that I know very well - the Three Peaks in fact (this is Yorkshire and we don't acknowledge those other three peaks).

Pen-y-ghent

I've been up Pen-y-ghent at least two dozen times – it's my go-to mountain when I can't get further afield or the weather's not entirely dependable, or I just want a leg stretch rather than a challenge - but I've probably been north along the ridge to Plover Hill only five times. Why? Blanket bog. Once you drop below the 640m contour on the ridge, you're on the black stuff until you get back up to 670m. That's almost 1.5 km away if you handrail the fence, and we all handrail the fence because it a) follows the public right of way and b) makes navigation easier. So there's a rut along that fence that you and I have made and it's just getting deeper and deeper and gradually wider as we try to keep to the outer edge for firmer footing. We're eroding the vegetation and exposing the peat so that it will simply weather away into the atmosphere. We're doing that – you and I – for our leisure.

How can we reduce the impact of our footprints? Well, let's all slow down. Route marching through blanket bog is bad for us and bad for the bog. We stagger, trip, lose our footing, perhaps twist an ankle; the bog loses its protective layer of vegetation and is eroded by wind and rain. If you want to get to Plover Hill at pace, go when it's under a metre of snow. Otherwise, go in the summer, take your time, make a day of it. Spread out, properly, get away from the fence – it's all CRoW Open Access up there. Stop and take a look at what's below your feet. Once you take the pace off, the going is much less treacherous, and there's some fascinating stuff down there.

Sphagnum for a start; look for bright green clumps of moss – and not just green; it comes in all shades of red, brown and yellow. Pluck a bundle and squeeze it out – you'll be surprised just how much water it releases (put it back, though, please). By holding so much water, it maintains a wet environment in which other plants struggle to compete, and also in which peat forms.

Depending on when you're there, you could also see cotton-grasses in seed, white heads bobbing in the breeze; bilberry dark with berry; perhaps even the carnivorous round-leaved sundew folding an insect in its sticky, tentacled leaves. Have a listen – a meadow pipit piping somewhere in the foliage; a wheatear's rattling alarm call from the fence line; in the distance, the long, mournful looping of a curlew; the deep pruk of a raven. We should enjoy mountains for themselves, not just for the tick.

The old Three Peaks route dragged you across Black Dub Moss, and that really was hard going. The Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority put in a new path taking you onto the Pennine Way without crossing the bog – longer for you, but faster and drier, and much better for the habitat.

Whernside

The summit of Whernside looms over Greensett Moss – a flat pan of peat hemmed in by the main ridge to the west and Greensett Crags to the east. The ascent takes you over the Settle Carlisle railway on a splendid Victorian aqueduct, up past Force Gill and around the edge of the Moss. You really should take the time to look at both the aqueduct and Force Gill waterfalls – they are quite lovely.

Decades ago, the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority was trying a range of different tactics to control erosion. I'm sure I recall an area covered in plastic mesh; it was like walking on a massive green waterbed. As the path curved around the bog, it became rutted, and wider and wider and wider.

The National Park Authority have come to the rescue again, with a magnificent flagged path taking you round the blanket bog. It really is a thing of splendour and I can only imagine what a back-breaking task it must have been to lay it. And because it provides firm, safe footing, people use it. They're not tempted out onto the peat and this helps to protect it. Around 100,000 people attempt the Three Peaks every year, and that's not taking into account those summiting the individual peaks. That's a colossal strain on the environment (and also on local services, but that's for a different article). The habitat can't possibly withstand 200,000 feet traipsing out to avoid the erosion caused by the feet that preceded them.

By all means, take a wander down to the Moss and the tarn there – it's bleakly beautiful – but not in a huge group. Again, slow down, enjoy your immediate surroundings. Or just skirt round it all on the splendid path, give thanks to the National Park, and enjoy the amazing view from the top. On a clear day, you can see the Howgill Fells and even the south eastern fringe of the Lake District. Don't forget to look down, though, at the amazing habitat below you.

Ingleborough

Further on – come on, you can do it, last summit – the route winds through Ingleborough National Nature Reserve, jointly managed by Natural England and Yorkshire Wildlife Trust. The limestone pavement you are walking through – Yorkshire Wildlife Trust's Southerscales on the right, Natural England's Scar Close on the left – is astonishing. You need permission from Natural England to visit Scar Close, but it's worth it – some of the best in the country and nothing like the bare, denuded slabs you'll find at the top of Malham Cove. As you summit that steep wall above Humphrey Bottom (nope, no idea), you'll come to a saddle between Ingleborough and Simon Fell. Look to your left (roughly north east) and you'll see some of the early attempts to tackle peat erosion in the Dales.

There are large areas of bare peat running up to Simon Fell summit. Unless it's under hard snow, it's a nightmare to traverse. My first and only trip to Simon Fell summit was in 2014, and it was not much fun. Yorkshire Peat Partnership (YPP) led by Yorkshire Wildlife Trust tried to stabilise the peat and re-cover it with vegetation back in 2013. This is peatland restoration at its most extreme, in an inhospitable climate for vegetation to re-establish itself, and the restoration has not fully taken; this is why you can still see so much bare peat. YPP will be back – with new and improved techniques. In the meantime, be kind to Simon Fell. If you want a slightly different view back to Pen-y-ghent, skirt around the bog and make, instead, for Park Fell – it's lower, but firmer, and you won't be making more erosion for YPP to repair. Thank you.

Why, you may ask, should you care about all of this? What difference does it make?

I topped my first Dales summit (Simon Seat, surrounded by blanket bog) when I was 12. I'm 49 now and I really only started thinking about peatlands in January 2018 when I started working for Yorkshire Wildlife Trust.

Blanket bog is Yorkshire's largest semi-natural habitat. It's amazing for wildlife. As well as the species I've already mentioned, you might see short-eared owl, merlin, ring ouzel, bilberry, bog asphodel, common lizard, adder, field vole. It seems vast and green and a bit lifeless if you're just trudging past, but stop, open your eyes and ears (and nose) and these are Yorkshire's rainforests. Blanket bog erosion affects downstream biodiversity too, as peat is washed down into the river catchments changing the environment for the mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies on which our fish feed.

Not interested in wildlife? Ok, I'm baffled, but fair enough. Peatlands are the world's largest terrestrial carbon store. Peatlands cover around 10% of the UK's surface and yet store more carbon than all the forests of the UK, France and Germany combined. Well-meaning but misguided agricultural policy in the 50s and 60s encouraged landowners to drain our peatlands. As they dry out, they lose the vegetation that maintains them and, for various reasons, the peat becomes bare. Once it has lost its protective layer of plant life, what isn't washed into the river system oxidises back into the atmosphere. And dry peat is a lot less resilient to fire.

Don't believe in climate change? Well, 98% of science is against you, but ok. Do you live on or near a floodplain? Say, perhaps, Leeds city centre? There's a misconception that peatlands soak up water like a sponge. That's not quite true – pristine blanket bog is already saturated – but it is true that blanket bog can help to slow the flow of water off the hills. One of the (many) problems with bare peat is that rainfall simply rushes across the slick surface and into the river system. This means that the very top of the catchment is dumping water into the rivers as fast as it possibly can; this is bad news for anyone living toward the bottom of the catchment. The rough surface vegetation of Sphagnum and cotton-grass hummocks and hollows on healthy blanket bog slow water down and can help to reduce massive peaks flows during storms.

Don't live on a flood plain? Good for you, but I bet you need drinking water. Research from University of Leeds estimates that in the UK, 72.5% of the storage capacity of reservoirs is fed by water from peatlands The study also shows that removing peat sediment (in the form of dissolved organic carbon) from drinking water draining from degraded peatlands represents the largest treatment cost for water utilities in the UK. Water companies are filtering peat from your drinking water and then sending it to landfill. Part of your water bill pays to send something to landfill that should have stayed on the hills in the first place. And, to be clear, this isn't the fault of the water companies. Collectively, as a society, we have failed to value the many benefits our amazing peatlands provide.

So what can we do to help protect these beautiful habitats?

Well, as a starter for ten, we can stop using peat based compost. It's true that very little peat is milled from upland blanket bog in England, but it's all coming from peatlands somewhere, and peatlands everywhere are valuable. There are some very good alternatives available on the market now – some of them actually outperform peat – so there's no excuse. I hope we can all agree that clean, healthy drinking water is more important than herbaceous borders.

The UK government is currently working on an Environment Act for England - the first for 20 years – which is great news. The first draft of the Bill (a Bill goes on to become an Act if parliament passes the legislation) was published recently. Get in touch with your MP to let them know how important the environment is to you. The Wildlife Trusts have some resources to make this easy to do. In England, DEFRA is currently working on a peatland strategy – if you live here, you could also stress how important that is to you.

At a local scale, why not volunteer? As well as the Yorkshire Peat Partnership in there are groups all over the UK working to restore peatlands – Moors for the Future in Peak District, the Flow Country in northern Scotland, Exmoor Mires Partnership in south west England, the Pumlumon Project in Wales, the CANN Project in Northern Ireland. They're always grateful for a helping hand, and healthy peatlands give you a better experience in the great outdoors.

And on a Yorkshire note, Yorkshire Wildlife Trust is fundraising for the Yorkshire Peat Partnership to continue its vital work to restore the 70,000ha of blanket bog in Yorkshire. Since 2009, YPP has begun restoration on almost half of this, but that still leaves us 35,000 hectares to go at, so every penny counts.

- You can support the appeal here.

Lyndon Marquis is the Communications Officer for Yorkshire Peat Partnership

- My Scrambling Fall 21 Aug, 2017

Comments