Did you know that you can safely climb mountains without any of the recommend equipment? Map, compass, warm clothing, first aid kit, phone, torch, emergency rations… High in the results of any internet search for "hill walking kit list" are links to major shops; you'd almost think they profited somehow.

Don't get me wrong, I do think all of those things are valuable at times, I don't think it's all a marketing conspiracy, and I don't bear any grudge against the retailers. But, following feedback from various quarters on my smartphones in hills article – in which I offered an opinion that we can sometimes dispense with paper maps – it strikes me that the outdoor community as a whole places too much emphasis on equipment over judgement.

A friend once rang me for advice when lost on a mountain. She carried not only a map and compass, but also a complete copy of Eric Langmuir's weighty training bible Mountaincraft and Leadership. Needless to say, it didn't help - because equipment is at best loosely related to safety.

Where, then, does safety come from?

Surely it comes through assessing the limits of the whole group, and acting appropriately. For those seeking an adrenaline fuelled moment of glory, this needn't spoil the fun: limits are there to be pushed! But it's worth building up in stages to get a feel for where they are in the first place (also, go and find somebody better to learn from – it will likely push your limits more as well as make you safer).

The question 'am I fully equipped?' is far easier to quantify than 'am I acting appropriately with respect to my limits?'

If something major goes wrong, then all bets are off, but you should consider the effect of even a minor mishap on your plan. If you got lost, how far past your limits would it take you? Perhaps you could harden up and deal with it. Or perhaps one of the weaker members of the group would run out of energy, then another become hypothermic while waiting for them. You wouldn't be the first people to fall into that particular trap – mountain bikers in particular are terrible, in my experience, at carrying spare clothing.

Taking precautions & having a backup plan. This is where equipment can come in: warm clothing in case the weather turns or you have to stop moving; first aid kits to patch up an injury; map and compass to guard against a phone failure. Even so, the usual last line of defence requires no specialist equipment at all - tell somebody else where you are going, when you expect to be back, and what you want them to do if you're not.

Notice two things, though: (1) backup plans only take effect once something has already gone wrong; (2) backup plans themselves have limits to their effectiveness. Both of these points only serve to emphasize the importance of a skilled assessment of limits in the first place.

Pondering these nebulous questions, it's easy to understand the temptation to focus on a kit list instead. For each item, you either have it or you don't, and hence the question 'am I fully equipped?' is far easier to quantify than 'am I acting appropriately with respect to my limits?'. And indeed the latter is not an easy thing to teach, so lists of recommended equipment for particular activities certainly have their place in educating novices and instructors alike.

But what is easily measured isn't necessarily the same thing we're actually trying to achieve. Economist Charles Goodhart is credited with saying that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to become a good measure - a problem which is rife in both education and healthcare as well as national economic policy. This effect can combine unpleasantly with risk compensation – where somebody who has taken precautions might choose to partake of a more dangerous activity than they would otherwise have done. For many of us, this is exactly the desired outcome; modern equipment allows us to take on challenges we might otherwise have baulked at. A lightweight axe, crampons, rope and a few extras allow us to walk over glaciated terrain that would be foolhardy without them! But a slavish focus on the measurable kit list, rather than the hard-to-measure target of properly assessed limits and backup plans, can give a false impression of safety. Couple this with risk compensating behaviour, and having all the kit might actually place us in greater peril.

"All the gear but no idea" is a common criticism of novices in the outdoors, but in highlighting the importance of training in equipment use I think this slur misses the main point: if we push our limits, then by definition we set out with incomplete knowledge. It's easy to feel smug deriding an inexperienced group that made some poor choices and needed rescuing, but safety in pushing limits isn't really about how much "idea" you have at all - it's about keeping the unknowns manageable, whatever your level of practical competence.

But why not carry the gear anyway?

One reason not to carry equipment is the ability to travel fast and light: if we stuck to the Victorian kit list, Alpine ascents would still require large teams of supporting servants, so it's still valid to question what we can ditch from our current inventory. For example, in a UK context it might be fair to say that most items in a standard first aid kit (plasters, blister pads) exist so you can continue to have fun despite a minor injury, rather than save a life from a major one. That's not to say they're not worth having, but don't confuse a couple of plasters for safety equipment! (And don't ditch the entire first aid kit: a medic friend has convinced me that large wound dressings genuinely have lifesaving potential).

More fundamentally however, by focusing on lists rather than hard-to-measure questions of limits, we contribute to that part of our culture that continually poses a threat to adventurous pursuits. Locally to me, in a case that has dragged on for two years now, the Crown Estate employs several full time security guards at our collective tax-paying expense to keep us out of the disused Livox Quarry - an excellent wild swimming spot easily linked into a Wye Valley walk or climb. While other factors are certainly at play, it's hard not to think that such frustrating waste of public resource (both the money and the swimming spot itself) wouldn't happen in a society where everyone was better at assessing their own limits in the first place.

And what about paper maps?

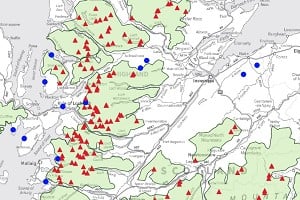

Going back to the question of abandoning paper maps for digital, my own main reason for ditching the paper is that I haven't had it available. I often take a spontaneous walk to break up a long distance drive, something that wouldn't otherwise be possible without a very extensive map collection in the car at all times. Two years ago I took a road trip around Norway with little idea where we'd end up – a full set of maps at Norwegian price would have added considerable cost! Navigating by phone alone, we didn't set out in poor conditions, and had the following backup plan:

- If one phone breaks, use the other one

- If slightly lost, retrace steps back to the car

- If utterly lost, go downhill and seek help - following the compass if needed to ensure ending up in the right valley

Avoid going where these tactics won't work, or if you do, remember the way back. In craggy terrain (we scrambled up the amazing Vågakallen for example), it may not be possible to descend directly. But in any case, maps become progressively useless as things get more vertical, and craggy terrain is full of recognisable landmarks, if you're paying attention.

It's worth noting that three of these tactics also apply if a gust of wind takes your paper map away from you, and the final one is the default option for cavers almost everywhere, as cave surveys usually fall on a spectrum between hard-to-read and non-existent.

Do I think maps and compasses are outdated? Absolutely not; particularly for their role in teaching good navigation skills, which are essential whether or not you carry a physical map. If our (currently 1 year old) daughter ever shows interest in outdoor adventures, I will certainly offer to teach her some map skills. But I was teaching her to assess limits before she could even walk: well done little one, you've climbed the stairs… how are you going to get back down?

Crispin Cooper has been climbing for 20 years and has certainly been responsible for some poor assessment of limits at times, but considers that an essential part of the learning process. He blogs about adventures physical and mental here

Comments