In our attitude to landscape it often seems we know the price of everything, but the value of nothing. Tim Chappell laments the monetising of a little gem in the hills of Fife.

That wood next to Norman’s Law: an elegy

It had a rookery. When you went up Norman's Law at dusk, there would be homing rooks and jackdaws making spooky, cawing echoes around it. There were greenfinches and bullfinches. It had clanking pheasants and wobbling herons, like umbrella-stands with wings.

I heard a cuckoo there once, and very often there was a buzzard drifting over the tips of the trees.

In autumn the larches in it would turn auburn-gold, the birches would turn yellow-gold and then go bare; the deciduous species would become black bones of trees.

On a winter night of full moon, you could ghost through it in photographic negative with the ice-pools cracking under your feet, and in spring it had bluebell-filled clearings, and moss as thick as your arm on every branch.

"What is wrong with us humans, that we can look at a beautiful landscape and see it only as an array of pound notes stapled to the ground and awaiting collection?"

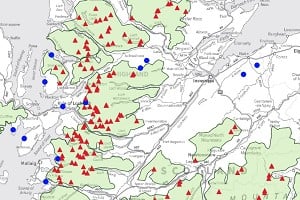

Round the back of it, at the fence-edge under the little hill next to Norman's Law that is, delightfully, marked on some maps as Whirly Kips, there was a kind of secret ancient-Britonish passageway, along the mossy hillside, where I used to go to sit and think, or alternatively just to sit, in the middle of nowhere with not a human or a road in sight.

I went up Norman's Law last week, and there were tractors and diggers ripping that wood apart. The path from the roadside is knee-deep in black ooze, and twice the width it ought to be.

Now I'm not even opposed, in principle, to "forestry operations", or to the "harvesting" of "mature woodland". (Less opposed than I am to soothing bureaucratic euphemisms, anyway.)

But the destruction of this beautiful little wood... It's only a little thing. But isn't that the point? Isn't natural beauty, precisely, a mosaic of many little things?

In my pessimistic moments I wonder what exactly it might be that human beings are good at, other than very thoroughly fucking things up.

"It's so old and so stupid a mistake. When will we learn not to make it?"

I wonder how much the wood from it can be worth. They have probably three guys and three big hired machines, working flat out at smashing it up and taking the wood away, probably for about three weeks.

So for this to make even economic sense, the wood from that wood must be worth, I'd have thought, about £10,000.

I wonder if it is.

And is economic sense really the only sense there is? There's this familiar slide from being unquantifiable, to not being in the equation, to being quantified at zero. It's so old and so stupid a mistake. When will we learn not to make it?

What is wrong with us humans, that we can look at a beautiful landscape and see it only as an array of pound notes stapled to the ground and awaiting collection?

And what is wrong with us, that we think that anyone who takes this attitude is "realistic" and "hard-headed" etc, whereas anyone who sees beauty as beauty is sentimental and subject to illusions?

That, surely, is exactly the wrong way up. Because there is nothing more overwhelmingly obvious than beauty, particularly natural beauty, like the beauty of a wood: if anything is real that is. Whereas there has not been a greater nor more pernicious illusion in the history of humanity than money.

And once we have trashed the wood to get the money, what will we do with the money?

Buy another wood, perhaps?

This isn't a poem about Norman's Law or the wood on it - if I have one of those, I haven't got it yet. But it is a poem about place, and about how easily our sense of place, and the places that are sacred or holy or special (or whatever you want to say) to us, are destroyed. And it is a poem about Scotland:

Still the blood is strong

There every foot of field-end matters,

each river-pool is itself;

every stone is a sacred standing stone,

every hill a sith of the old ones;

here each street is the same

for mile after mile.

It only feels like what they had cannot be lost.

It only feels abiding unchanging home.

The bulldozer and the eviction writ,

north and south, work the same.

They walked into London’s sameness

with heather-seeds still in their socks,

the plough-callus still on the insides of their thumbs,

the mark of the sheep-tick still fading behind the knee.

Kincardine O’Neil, Aberdeenshire, 7 July 2008

Comments