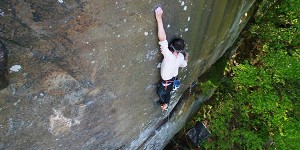

Highballing is the most modern form of climbing. In essence, it involves climbing a high rock, with use of crash mats to offer protection. Mostly this protection is of the physical kind and a lofty fall is terminated in a soft thump, a directional prod from your friends spotting you, and a large exhale of breath as you sit back and gaze up at what could have been. The beauty of this approach is that it extends upwards the 'try hard' world of bouldering and brings the light freedom of short solos within the realms of safety. The perfect highball should allow you to keep pulling, climb free and remain safe(ish).

Choosing your highball

At the centre of any memorable highball experience is the line itself. Typical highballs range from 5-12 metres in height and consequently, there's fantastic opportunity to have a decent length of sequence that takes on a really good line. The first step is a bit of soul searching: what are you after? Arete, groove or wall? Something steep or a slab? In a valley or on a mountain? Sunny or shady? If you find the right rock, in the right place, with the right people, the joy will start to effuse and the whole experience becomes one of perfection.

What grade is the right grade?

A big part of choosing the correct problem is picking something of a suitable difficulty. A climb that's too hard is obviously going to stop you in your tracks, but it might even stop you getting off of the ground. Hard routes often rely on subtle body position to stop you wrecking your skin, the climb, your shoes, or from getting injured. It might also be the case on 'sketchier' problems that a certain level of strength is needed to jump off safely, downclimb, or traverse off. In short, too hard can be both unpleasant and dangerous. There is a small caveat here that in those most magical of moments, really difficult climbs can inspire to such a point that the seemingly impossible becomes a reality. But it's best to play it safe 99% of the time.

Conversely, a problem that is too easy can also be an annoyance. You don't want to lug 10 mats up to behind Pavey Ark, only to cruise up your chosen route first go; a couple of lengthy falls onto your pad stack always makes you pleased to have brought them up. A further danger of easy routes is that they allow you to get very high very quickly and may also breed complacency, which is a ripe spawning ground for shattered limbs.

For a first experience, it's a good idea to drop a couple of grades from what you usually boulder, or add a couple of grades to what you usually onsight on Trad. If you're unsure as to even the ballpark you'll be operating in, pick a crag that has a good range of problems. Start with something manageable and work up.

For the day or long term?

Organised fun is the best kind of fun. Everyone loves obsessing on the line they're going to try next weekend and with highballing, preparation and a bit of thought can pay dividends. Even a fairly short project with a 15-minute walk-in is a logistical challenge. Have a frank chat with either yourself or your friends about whether you think this is going to be something you could get done in a session, or whether this is going to turn into a protracted siege. The two experiences are very different and may rely on very different tactics.

Highball, Skyball or Dieball?

Not all highballs are created equally. With the term being quite a modern invention, it therefore has a bit of a 'cool air' about it. It's used an awful lot by people to describe very different things. At its lowest in height, 'highball' can be used to describe something that goes only a little bit above a typical boulder problem. On these kinds of problem, a fall from any point on the route may be a little worrying but is highly unlikely to result in injury if all the steps described elsewhere in this article are employed properly. 90% of highballs probably fit this category and it's on this terrain that tactics, style, and logistics are best learnt.

Extending the highball takes us into the realm of the 'Skyball'. Into this category would fall short grit-style routes that are now safer above seas of mats. How far into the last and next category a Skyball goes is dependent on your own skills climbing, falling and stacking mats, as well as how many mats you take. The beauty of the Skyball is that you can be climbing difficult moves for 8 metres or so, entirely unhindered by ropes and without the terror you'd have on the solo.

At this point, we need to be very clear about the height of falls and talk about them without hyperbole, exaggeration or ego. A fall with your feet at 6 metres is a big fall, even onto a huge stack of mats. Falling with your feet at any higher than 8 metres is likely to result in injury, without some pretty wild cat abilities. You'll regularly see people talk about 8, 10 or 12 metre highballs, but if anyone falls off from 12 metres, they're going to be knackered: don't be fooled. The Skyball height occupies this very upper limit of where you can actually realistically fall off, which may not be very high at all if the landing is bad.

If you've experienced a few Skyballs and you've still got the itch for a little more, then the esoteric world of the 'Dieball' might just be for you. The distinction between the Dieball and Skyball is that on a Dieball you get into a real 'no fall zone', usually with hard climbing low down and then an easier, but horrifically gripping upper section. A famous example of this would be Kevin Jorgeson's ascent of Ambrosia, in Bishop, where a hard section of Font 8A bouldering at a highball height, led into a F7c section, where he was effectively soloing. As the name 'Dieball' suggests, falling off sections of these routes is likely to have serious consequences and quite often all or part of the route is pre-inspected prior to an ascent. This realm has an obvious crossover with soloing and Trad climbing, and on occasion it has even been known for climbers to place the odd runner near the top, producing a kind of hybrid 'Ropeball'. It's easy to see how this style of approach has already revolutionised both hard Trad and bouldering alike.

Possibly one of the biggest nails in the coffin of bold Trad routes in the UK was the demonisation of Headpointing. As stylistically sound as a no pre-practise approach may appear to climbing bold lines, abseiling down or top roping a pitch can allow you to climb it more safely, quicker and even reduce wear on the rock. Ultimately whether you abseil a line or not is a personal decision, but if you're going somewhere remote that is going to be difficult to get back to, you might want to consider the use of a rope in the planning stages.

How many pads?

Having enough

The invention that made it all possible. Bouldering mats are fundamentally wedges of foam inside a textile case. This foam is generally a mixture of open cell, which is light, squishy and does very little to actually slow you down; and closed cell foam, which is heavier, usually used in thinner sections than the open cell and is the main component of the pad that is going to protect you from rock protrusions. The open cell allows air to leave its matrix, whereas the closed cell does not. This makes closed cell a much harder material to fall onto but provides substantially more breaking. For highballing, you will want a pad with at least some closed cell foam in it.

Most pads will have either a sandwich, with two thin slices of closed cell, either side of a piece of open cell, or a piece of closed cell simply placed on top of the open cell. By combining both kinds of foam, the falling climber receives both a soft catch, as the open cell 'gives way', but then also a good level of resistance from the closed cell, which does the majority of the slowing down. Depending on the construction of your pads, you may get a harder but more substantial catch if the open cell is 'trapped' under the closed cell.

At a basic level, lots of pads means lots of cushioning, but to optimise your stack you need to unzip your pads and have a look at how they're constructed. If you have too much hard closed cell foam at the top, you may not get properly absorbed into the stack and may even get bounced off of it. If too much of your closed cell is under the soft stuff, then you won't get anything like as much of the cushioning out of it, as you lose out of the bonus breaking from the open cell being trapped under the closed cell.

The dangers of too many

There are quite a few disincentives to using a lot of pads. The first is the effort of carrying them in. It is possible to carry up to 8 pads, but this is very cumbersome and unlikely to leave you feeling like you're ready for prime athletic performance. This is compounded if you are climbing alone or as part of a small group, where the burden of sponge lies more heavily upon you.

Even if there are three or more of you, each psyched and ready to carry half a dozen pads each, you're unlikely to be able to transport that many, unless endowed with a van. If you're limited by cars and have a lengthy journey, you'll need to make a calculation involving safety, number of people, size of vehicles and carbon footprint. It has been known for four people to each drive five pads to the crag separately, but this is perhaps a little ridiculous.

As well as the logistical problems of big pad stacks, it's also worth thinking about the safety implications. A large platform means a large drop off of it. This can be made even worse if the pads project out from a hillside. It is not unusual for the drop off of a pad mound to be almost as bad as the drop onto it. This is another reason to wear a helmet, but it might also be worth thinking about using a short rope to tie a spotter into the edge of the drop, forming a little fence to keep you nice and safe.

How to carry them in

The 8 pad high-end foot carry, whilst quite a sight to behold, may be a little bit like the highly advanced 19th-century stagecoach system: ultimately doomed to be superseded by a radically different form of transportation. In its simplest form, the convoluted methods described above may be avoided by either shuttling mats in two or three runs backwards and forwards to the crag or stashing them after attempts, if trying problems over a number of days. Failing that, two methods I have witnessed but never tried, are the sledge and the electric mountain bike. The sledge may be a plastic one or one on wheels, which is fine on forest tracks, but more effort than its worth on moorland and in woodland. The electric bike will cost you the best part of £1000 to get set up, but allows for easy shuttles of two or three pads at a time, without the expenditure of any energy: radical!

How to fall

Falling is an inevitable part of highballing and can be dangerous. Sometimes highballing can be safer than bouldering, as a larger surface area of the ground is likely to be covered with pads; the pads are likely to be thicker; and the risk is perceived by the climber to be greater, which often actually works to reduce unplanned falls. Needless to say, a higher "ball" means a bigger fall. A few tips might keep you safe.

If you look at any landing closely, there will be better and worse places to land. Rocks are the obvious things to avoid, but so too are small mounds, harder bits of earth, animal burrows, spikey plants or anything that is not going to give you a flat, soft landing. Spend a good while looking at and feeling the ground and make a mental map of the area below your problem. This knowledge will give you that extra bit of confidence when you glance down just before you commit to that high crux.

Bending your knees

This one sounds obvious, but is a real skill. You need to get to know your knees. Find how much resistance they have, the quirks of each knee, anything that feels funny in the soft tissue when you bend them. You want to be pretty loose and bendy when you fall, but not so elastic that you provide no braking force for the rest of your body. A little trick I used to practice this skill as a kid was to go to Whitby Pier and jump off onto the sand from progressively further along. It was surprising how high you could work yourself up to jumping off. This practice did cease however, when I kneed myself in the face.

Rolling it out

For those of you over 25, whose knees are starting to feel a little bit used, some strain may be taken off of your limbs, by rolling a fall out. The theory is that the gravitational energy is transferred sideways, rather than into your knees. This technique is also very useful on steep ground, or where the immediate landing spot is hard and there is a softer section to roll onto. There are of course significant hazards associated with any kind of block or obstacle in your path, so make sure you check this out thoroughly and know exactly how and where you're going to roll. It's probably also worth stretching your neck, back and arms out properly.

Briefing your spotters

Practice falling

Everyone has their own way of falling and some people are exceptionally bad at it. One foot should always lead. Similar to very fast downhill fell running, this first foot feels the ground it hits and you can get very quick feedback as to what you have hit. If this initial ground is hard, undulated or pointing a funny direction, your first leg can bend and allow the second foot to take the larger part of the force, or transfer the energy into your next movement. If the ground is good and soft, it can provide a large amount of braking, with the trailing leg supplementing this. Landing two feet at the same time allows for none of this adjustment and you take your chances damaging both legs.

Wearing a helmet

For a lot of problems, you may get away without one. If you're planning on rolling out problems, or there are hard objects in the landing zone, it's probably a good idea to have one. The main reason not to wear one these days is fashion, but some of the new very lightweight helmets are not only so light you forget you're wearing them, but also look great. Personally, I love a good helmet. For Skyballs and above, it becomes part of my ritual: shoes, chalk bag, helmet. It probably gives you an extra 2% confidence and about 100% more confidence to fully roll problems out, which massively reduces the risk of injury.

Modifying your landing

This one is a bit of an ethical minefield and is definitely not something that should be done below established problems: please don't start car-jacking bits of Burbage North down the hill. If you are, however, in a fairly undeveloped place, making early repeats, or trying things in new styles, it might be worth thinking about modifying your landings. This is best done in areas where there is an abundant supply of mid-sized blocks or logs that can be either wrestled or crow-barred into deep holes and gullies that a pad would otherwise not be able to cover. Before you start moving anything, think carefully about what your aim is and why you are doing it, make sure you have permission, aren't destroying any animal burrows or nests and that there isn't any flora that's going to suffer. You won't be getting any brownie points for having a ring ouzel skeleton below your new bloc.

Keeping good conditions

The usual factors will help good conditions: cool temperatures, low humidity, no direct sun. On top of this, there are a couple of things that are worth being extra diligent about on highballs. The part of the climb with the greatest possible dangers associated with a fall is the top out and as such, make sure you have a good look at this; give it a clean and have a decent idea about how you're going to get over. The top out is also often a point at which you may chuck a heel on, which changes your body position to one where a fall may be onto your back.

If it's a popular highball, a very soft brush can be used to get rid of excess chalk after each go. Never mind a wirebrush, stiff Nylon brushes should also be avoided on these kinds of problems. Your super soft brush can either be one mounted on a telescopic pole, in your hand as you stand on your mate's shoulders, or used when hanging off of a rope. If it's something more esoteric, it might be worth giving it a clean a few days or weeks prior and will almost certainly need a quick abseil to ensure it's in a climbable state. Dirty routes mean dirty hands and shoes. This makes the climbing harder, a slip more likely and more wear on the route. Take your time.

The future of highballing: Nets and Air

As with anything in its infancy, the future of highballing is blindingly bright. The potential for the development of highballing is massive in several directions. The obvious ones are how high and hard you can go. So far the cutting edge problems are either very hard and fairly low, or moderately hard and high. It takes a special kind of motivation to operate near your limit in a dangerous setting, but there are a lot of talented boulderers out there. Bouldering mats have already taken the edge off of several short gritstone routes, but pads are only set to get bigger, fatter and made of stronger stuff. At certain crags, with the right angled boulders either side, it's also possible that the world of gymnastic netting may be developed, to be used as a summer alternative to the ever-trendy "Snowballing". Whatever happens in the next few years, you know it's going to be exciting.

- TRIP REPORT: Franco Cookson's Journey to the Mirror Wall 25 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: How to Become an E10 Climber 1 Apr, 2023

- OPINION: The Blurry Line - When does a sequence become a line? 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: 2021: The Year of the Headpoint 15 Nov, 2021

- DESTINATION GUIDE: North York Moors Limestone 9 Apr, 2019

- ARTICLE: Franco Cookson's Guide to Headpointing 15 Jan, 2019

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Spittal Crag, Northumberland 16 Oct, 2018

- DESTINATION GUIDE: The Yorkshire Coast 16 Apr, 2018

- DESTINATION GUIDE: North York Moors 15 May, 2008

Comments