For Richard Hartfield, the precisely-plotted lines of an Alpine map have come to represent cherished memories of a very special mountain region throughout the seasons, and the friendships he's made there.

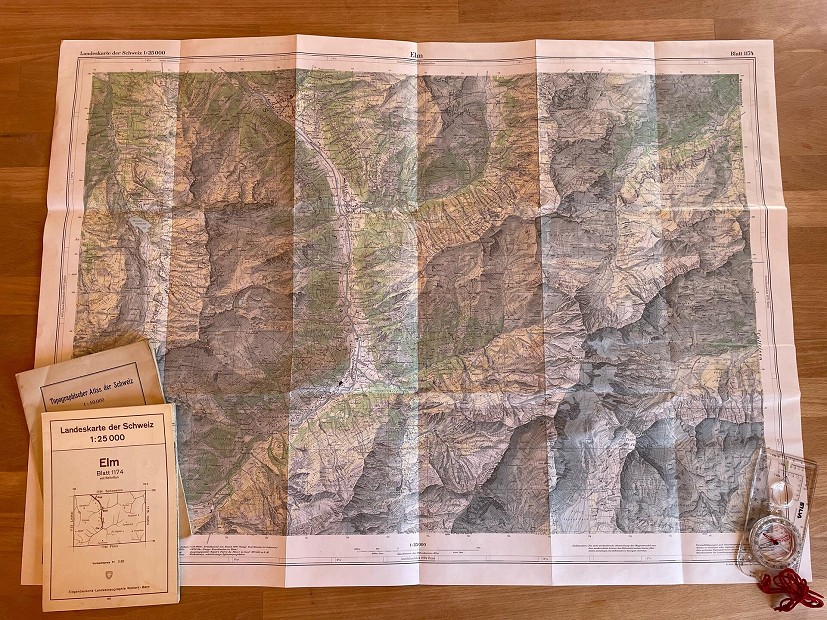

Swiss Topographic Map 1174 Elm

This Swiss topographic map of the Sernftal has been my guide to many months of exploration and cemented this little corner of the Swiss Alps as a home-from-home. Located in the central Swiss canton of Glarus, the Sernftal is a valley on the northern flank of the Alps. Known locally as the Glarnerland, these cliff-strewn and steep mountains haven't lent themselves to the development of large ski resorts or major roads. There's also an absence of any 4000-metre peaks. Perhaps this is why the Glarnerland slips under the radar of most tourists, despite containing a UNESCO world heritage site and a historic wildlife reserve.

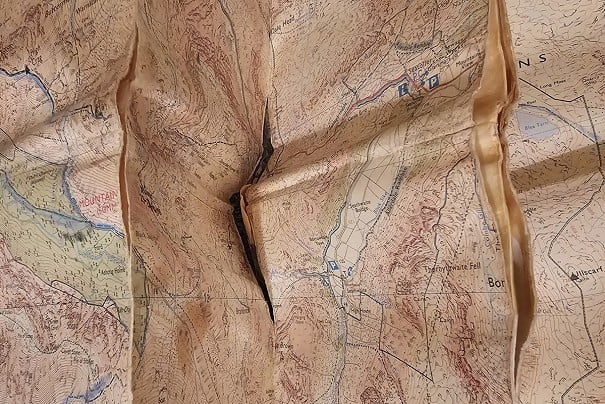

Just like everything else in the country, Switzerland's topographic maps are impeccably precise. Somehow, those diligent Swiss cartographers have succeeded in making order out of even the most chaotic and complex of mountain topography. With intricate cliff markings and easy-to-read contours, Swiss maps paint a vivid picture of the mountain landscape. With the Sernftal map, I can wander across karst plateaus; alpine ridges and forested slopes without ever stepping outside. It's been my guide to discovering the valley during every season of the year.

My first introduction to the Sernftal and its map, came with volunteering at a family-run hostel in one of its tiny alpine villages. It was April, and the spring snow line still came down to 1800 metres. This left the highest terrain beyond my reach. My hosts, Florian and Nicole lent me a pair of snow shoes and using the map, I could adapt my hikes to meet the challenging snow conditions.

My outings required careful contour interpretation to steer clear of the frequent avalanches. The map provided clear information and led me deeper into the valley, surrounded by immense cliffs.

Much of the Sernftal falls within a 450-year-old wildlife reserve. I often saw groups of chamois grazing beneath the snow line. These animals would become my companions on many future walks.

Florian and Nicole welcomed me back to the hostel again during summer. Paths, streams and other terrain features on the map had emerged from beneath the receding spring snow. I couldn't wait to get stuck into the higher terrain. I studied a deep, slicing gorge called the Tschinglen that lay high in the Sernftal. It gave access to tiered cliffs and hanging valleys, beneath a ridge topped by 3000-metre peaks. The map showed a trail that somehow managed to ascend the cliffs of the gorge.

Thanks to the generosity of Florian, I got to help repair this trail. I joined him and a team of trail workers on a 2600 metre-high pass above the Tschinglen. The 2D landscape that I'd studied on paper now stretched beneath me in 3D. Our job was to clear rock fall and avalanche debris which had swept over the path during the winter. It also involved meticulously digging drainage channels across the path at regular intervals. I finally understood that the trail on the map could negotiate such a precipitous and crumbling landscape only because it was carved out again each year. The Swiss are just as rigorous about maintaining their hiking trails as they are about keeping their streets free of litter.

Heidi, one of the trail workers, told me about a trail project that she had worked on. It was a new, long-distance hiking trail called the Via Glaralpina. It traversed the entire canton of Glarus in a 230km loop. My autumn plans were sorted. I started the Via Glaralpina from the hostel in late September and for nine days, the trail led me around the Glarnerland's highest peaks.

Like giant slices of cake, many of the cliffs above the valley are intersected by horizontal layers of rock. These lines are known to geologists as strata. Created by colliding tectonic plates which thrust huge swathes of rock upwards, the strata reveal how the landscape of the Glarnerland was formed. One strata in particular continues for many kilometres across the surrounding peaks and beyond the fringes of the map. The locals call it the 'magic line' and it connects the valley to the wider landscape. Soon it would be hidden again beneath the winter snow.

In January, I was back to help build a bouldering wall in the hostel basement. The snow line carpeted the valley floor and boulder fields that I'd scrambled across during summer were transformed into smooth slopes.

Not only had my connection to mountains grown, but so had my friendship with Florian. On each of my visits, we'd spent many evenings musing over the map and choosing our next climbing project. This winter was no different as I learned how to ski tour with him.

Exploring the Sernftal during each season revealed new dimensions to the map. Countless experiences are now woven amongst trails, contour lines and intricate cliffs. These carefully-plotted lines on a page have come to represent some of my most cherished memories, places and friendships.

Comments

Looks a tremendous place, Richard. And beautiful cartography.

Makes me want to visit Glarnerland. I'd never heard of it

It's a lovely region Norman, and the Swiss maps are works of art!

It's a great place to visit in any season of the year. Really accessible from Zurich, and very quiet!

Just been looking up the geology - not 'strata' actually (which are, basically, successive layers of rock laid on a seabed or similar) - I think we're talking about the Glaurus Thrust, where a slice of landscape (a nappe) has been shoved sideways across the top by the tectonic movements – in this case Italy being shoved northwards by the arrival of Africa. Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glarus_thrust has a great pic of what I think is your 'magic line'. Equivalent in Scotland is the much older Moine Thrust shoving central Highland schist in over the top of the Torridonian. And while I'm being a know-it-all, the Tschingelhörner will be named after the dog Tschingel, climbing companion of English explorer William Coolidge.