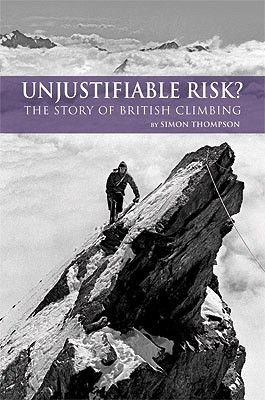

| Unjustifiable Risk? The Story of British Climbing

by Simon Thompson Pages: 400 ISBN: 9781852846275 Published: 16 Jul 2010 by Cicerone Price: £20.00 To an impartial observer, Britain does not appear to have any mountains. Yet the British invented the sport of mountain climbing and for two periods in history British climbers led the world in the pursuit of this beautiful and dangerous obsession. Unjustifiable Risk? is the story of the social, economic and cultural conditions that gave rise to the sport, and the achievements and motives of the scientists and poets, parsons and anarchists, villains and judges, ascetics and drunks that have shaped its development over the past two hundred years. Climbing has both reflected and influenced changing social attitudes to nature and beauty, heroism and death. Over the years, increasing wealth, leisure and mobility have gradually transformed the sport from an activity undertaken by an eccentric and privileged minority into a popular part of the leisure and tourist industry. But while much has changed, even more has remained the same. Today's climbers would be instantly recognisable to their Victorian predecessors, with their desire to escape from the crowded complexity of urban life, and willingness to take potentially unjustifiable risks in pursuit of beauty, adventure and self-fulfilment.

Buy Unjustifiable Risk? The Story of British Climbing direct from www.cicerone.co.uk or at your local climbing/outdoor or book shop.

|

Britain has a rich climbing literary tradition. Climbers and mountaineers love writing about what they have done, and we love reading about their adventures. If you were to try and recommend, perhaps to a new climber, just one book that would give them an overview of our history and a starting point to explore the hundreds of 'autobiographies, biographies, histories, memoirs and journals published since mountaineering's earliest days', you would be hard pressed to do so. This is what Simon Thompson with his book, Unjustifiable Risk? The Story of British Climbing has attempted to do. Ed Douglas takes a critical look.

Mick Ryan

'History,' as Napoleon once said, 'is a myth that men agree to believe.' Gosh, that applies to climbing. We love our stories, the famous anecdotes that get handed down through the generations. They have a kind of totemic symbolism that captures what the game is all about – or what we'd like it to be. The question is, are they true? And does it matter if they're not?

Simon Thompson's new history of British climbing Unjustifiable Risk? has all the great yarns. He says at the outset, quoting Flaubert, that writing history is like drinking an ocean and pissing a cupful, and labouring through his bibliography I can sympathise. The philosopher Daniel Dennett said that a writer is just a library's way of making new books, and Thompson might agree, having been at the mercy of his gigantic collection of climbing literature.

What he hasn't done is any original research. We have instead a précis of many, perhaps most of the autobiographies, biographies, histories, memoirs and journals published since mountaineering's earliest days. If you've never read any climbing history before and you're looking for a snappy introduction that covers all the bases, then this is the book for you.

Thompson writes crisply, as you might expect from someone who runs ginormous companies for a living, and cracks through everything at a brisk pace. Imagine if the Economist wrote a climbing history and you'll have it about right. He mixes short sketches of the principal players, some shrewdly concise, others, like that of Leslie Stephen, less so, with social history and reports of significant ascents. The account really sings when he describes an individual's climbing style, as he does with Colin Kirkus.

The problem with only drawing on published sources is this: when we follow a mountain path laid down by all those who have gone before, we're presented with one view of things. Strike out on our own, however, and we see things from a fresh perspective, one that might reveal hidden crevasses or alternative routes. This, I think, is the fundamental problem that lies at the root of Thompson's interpretation.

His paradigm is a familiar one, perhaps too familiar. Posh and eccentric Englishmen with time to kill and enthused by a new appreciation for mountain landscapes invent a new sport, climb everything in sight, get a little complacent, fight a world war which kills a large number of them, get more complacent and resent the first stirrings of climbing's popular appeal, fight another war, get supplanted by the working classes, who in turn get overtaken by university students before growing consumerism allows a small cadre of professionals to take over. That's it, I think, in a nutshell.

The problem is that the published record can distort things. Most books on mountaineering are about Everest. True, Everest was important, but surely the time has come to take a broader view, because the picture behind the obscuring mass of Chomolungma is fascinating. First example: while we have yet another rehash of the imperialist attempts on the Big E between the wars, there is absolutely no mention of the 1938 Masherbrum expedition, when a small team making the first attempt almost reached the summit of this stunning peak of 7,821m. (It also cost Robin Hodgkin, one of the great figures of pre-war climbing his fingers and toes. He isn't mentioned either.)

It's not surprising, perhaps, that Thompson ignores it, because it's not mentioned in Walt Unsworth's Hold the Heights, or in a more recent history, Fallen Giants. Although it is in Abode of Snow, Kenneth Mason's now elderly Himalayan overview. Why avoid what was in many ways a landmark British effort? Thompson makes great play of the fact that the toffs at the Alpine Club were hopelessly out of touch by the 1930s – and many of them certainly were – but the truth is more complicated. There were several influential climbers – some of them from the hateful upper-middle classes – whose ethical position was very similar to that of Thompson's heroes in the late 1970s. In fact, there never was a break in lightweight Himalayan climbing, as Thompson insists.

Second example: the ascent of Everest in 1953 was unquestionably a throwback to the 1930s, and the Commonwealth team were certainly not in the premier league of world climbers, but it's wrong to suggest as Thompson does that it was simply good logistics and equipment that got Hillary and Tenzing to the top.

More frustrating is the glancing coverage he gives to the ascent of Kangchenjunga two years later, except to acknowledge the working-class hero Joe Brown for injecting some useful fresh blood. It still amazes me that proper regard isn't paid this outstanding effort. The team's route was hardly known, fraught with difficulties and they were only there to reconnoitre.

Being in his late 40s, it's perhaps hardly surprising that Thompson regards the late 1970s and early 1980s as a golden age in British climbing. I'm sure he's right, though. Looking at the depth of genuinely world-class talent and the range of important ascents they made, few would disagree. But the price paid was very heavy. With such a strong cohort encouraging each other on, it's not surprising that so many lives were lost. Thompson rightly mocks Edward Strutt for harrumphing while German and Austrian climbers surged ahead between the wars, but they paid an even heavier price in terms of lives lost.

I don't think Thompson ever truly gets to grips with what makes a great climber. He's very keen on grades, which didn't really mean much before the mid 1970s, and uses them to make awkward comparisons between different eras. Obviously, technical ability is important, but there's more to the sport than raw performance. British climbing has always prized exploration ahead of raw performance, and I think continues to do so. Although he does judge Mick Fowler's career thoughtfully, pointing out how Fowler swapped technical brilliance for a more fully realised way of climbing far richer than if he'd stayed on the dole in Sheffield.

But too often he reaches for the well-worn, clichéd version of this long and complex story. The Whillans' gags get trotted out approvingly, but they're wearing thin these days. Climbing in the 1970s, when Whillans' influence was at its greatest, was often a misogynist, intolerant place – it seems to me. But I guess that deadpan humour is one of the myths we agree on.

Thompson is generally very good on setting the social scene for each phase of climbing's development, but one or two aspects he sells short, particularly women's climbing. He misses, for instance, the links early women climbers had with the suffragette movement. And while he gives short sketches of the grander climbing clubs, there's nothing about the establishment of the British Mountaineering Council.

There are one or two errors, some small – Bill Tilman was 79 when he died, not 80 – some more significant, including the point that Tenzing Norgay was given the George Medal, not the more senior award the George Cross as Thompson has it. It speaks to the dismissive racism of the Foreign Office that Tenzing's role was belittled in this way.

Where Thompson gets things badly wrong, I think, is in his assessment of Chris Bonington. Of course, just because he's Britain's most famous climber is no reason to let him off the hook. Aspects of Bonington's career undoubtedly deserve a bit of a kicking. But Thompson's constant mockery becomes tedious after a while, and undermines the authority of what he says elsewhere. True, siege tactics aren't ideal, but in the early 1970s, when big Himalayan walls were first being tackled, they seemed appropriate. Bonington himself returned to lightweight and alpine style when it was clear such methods were outdated.

Thompson, however, sees Bonington as the antithesis of everything he admires about climbing. After speculating on whether George Mallory was a hero, he quotes Bonington as ridiculing the idea, making Bonington seem sour. But the footnote gives Thompson away. The quote is from Brian Blessed's delightful but wholly unreliable yarn about his uproarious trips to Everest. Why didn't Thompson just contact Bonington to check the provenance? Perhaps the answer wouldn't have suited his purpose.

Towards the end the shape and value of his generally sound analysis falls away, because, I rather suspect, his interest and understanding of modern climbing is weaker. Perhaps that's because the published sources he relies on aren't as good as those for the Victorian era. Yet a lot has happened since Thompson's youth, and there's a great deal to celebrate and reflect upon. Climbers now are socially more tolerant, fitter, safer and just as absorbed by it all; it's wrong to assume that climbing's glory days are all in the past.

|

Buy Unjustifiable Risk? The Story of British Climbing

|

Comments