My first brush with French limestone was in 1971 after a particularly snowy first trip to the Alps. Luckily my mate had heard about a place called Saussois so we bailed from the Salbitschijen and headed to central France.

Polished rock that would put Stoney to shame greeted us, along with elegantly dressed French climbers wearing big boots, breeches and long socks. They carried small wire brushes which were used to clean the mud out of their Vibram soles and most of them carried and used etriers. They made almost no attempt to free climb the routes, and indeed they sneered at our attempts to climb their polished horrors in our Masters and PAs. The routes were equipped with a variety of 'stuff' which we tried to supplement with our own gear. Rather unimpressed we moved camp to Freyr in Belgium and found much of the same there... Successive years, though more successful on the Alpine front, always seemed to be cut short by the weather and by the late 70s I abandoned Alpine exploits for the time being, in favour of the States.

"Page after page of great crag and action photos revealed crag after crag that I'd never seen before"

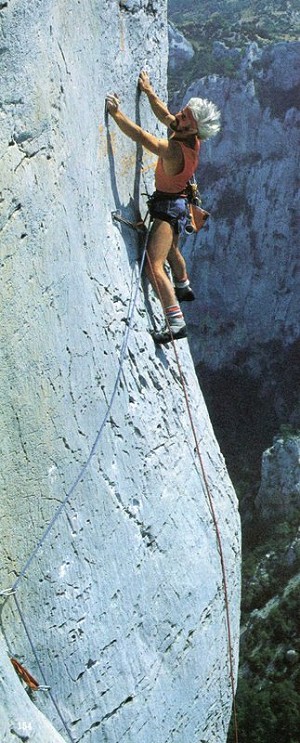

By 1982 I realised I'd missed a whole new French Revolution, in part spearheaded by one Peter Livesey and friends and ably abetted by his French look alike, J-C Droyer. The French were liberated! Livesey's little book 'French Rock Climbs', the fruit of his numerous trips in the late 70s, had appeared in 1980 and drew us Brits to places like Buoux, Buis, Sainte Victoire and the Verdon (and Saussois...) among others. 'Free-climbing' (as it was referred to in France, but in fact how we've always thought about climbing) was developing at a fair pace and particularly active were the French stars, Patricks Edlinger and Berhault. The fixed gear, however, was not much better than during the previous decade, but the notion of placing one's own protection was never entertained, despite Droyer's de-pegging of a number of crags – indeed their compact rock didn't generally lend itself to nuts etc. I remember doing TCF at Buoux when it was equipped with a selection of threads, pegs and a few rattly bolts. OVNI at Ste. Victoire sported threads made from thin wire, threaded around several times and the ends just twisted together...!

I spent much of the next year living and working near Gap, then Toulon, and explored most of the Provençal crags. It was during this period that equipment of the crags slowly improved and began to resemble more what we know today. Sometimes this was paid for by the climbers themselves, sometimes by the local communes who (mistakenly) saw climbers as a source of revenue. Much later the FFME (founded in the 40s as the FFM and transformed into its present form in 1987) sponsored the equipment of some of the newer crags. Sometimes a badly scribbled topo could be procured at the local bar or tabac for a few Francs and went a small way to reimbursing the equippers, but more often than not they didn't bother – after all, most new routers open new routes for the enjoyment of creating something and not with financial gain foremost in their minds – and so we were forced to rely upon bouche à oreille for info.

The above is to give the reader a very condensed, incomplete and not wholly accurate history of sport climbing in France – but more importantly to explode the urban myth of the 'local topo' sponsoring the crag's equipment. Sure in some cases it did that at the time, but now, nearly thirty years on for some of the crags, (and after numerous editions of topos, French and foreign alike) equipment has been paid for many times over. Of course the thorny issue of constant anchor/lower off replacement - and who pays for it - is as far from being resolved in France as anywhere else. Perhaps this is where we can all help by leaving a serviceable krab or maillon when we come across one we don't trust – and not to steal them when someone else has done this – they're not booty!

It might be fair here - and more accurate - to point out that the FFME do more than just provide funds for equipment. They draw up conventions with landowners to protect climbers and equippers interests. They sponsor guidebooks, either partly or totally, to certain crags. They negotiate access much as the BMC does in the UK. They have 60,000 members. They have 1,100 clubs affiliated to them. However, I see no reason why that should give them a monopoly on guidebooks any more than say, the BMC should demand the right to produce Welsh guidebooks.

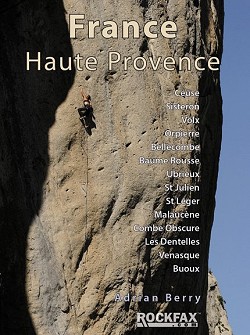

So, just about exactly 30 years after Livesey's little book, I have in front of me Rockfax's latest magnificent offering from Adrian Berry. A quick glance at the list of crags told me that I'd climbed at ten out of the fourteen and I'll admit to a little smugness - you know, been there, done that... which was immediately wiped from my face as I started to flick through the book (from the back towards the front – why do people do this – is it just me?) Page after page of great crag and action photos revealed crag after crag that I'd never seen before. So many more sectors have been added that places I'd not considered for years suddenly grabbed my attention again. If you, like me, thought you'd climbed areas out, at your grade, then be prepared to think again! I imagine a fair bit of debate went into the selection of the fourteen crags – some, like Buoux, St Léger, Céüse are unquestionable - but the inclusion of lesser-known ones (Malaucène), easier ones, shady ones (Venasque), sunny ones, crags at altitude etc, ensures that there is something for everyone and year-round.

"The result is just as stunning as everyone expects or, more correctly, demands from Rockfax these days"

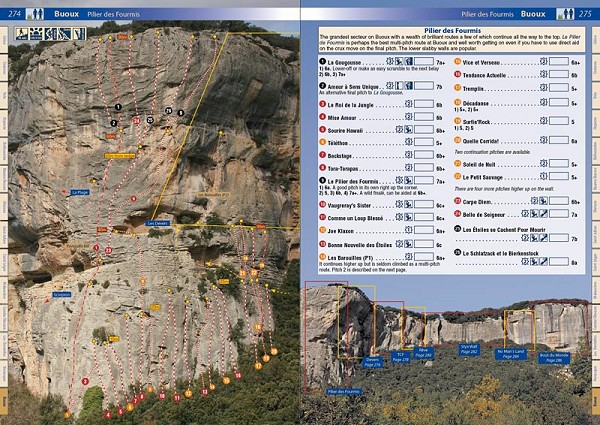

The next feature that hit me were the route lines – I could see them! Instead of the usual red dotted lines, which for me simply faded into the grey and orange rock, they are now red and white. A useful bi-product of this is that the lines are thinner (apparently they were too 'overpowering' if left at the usual width), and this in turn means that more crag detail is visible and makes identifying routes easier. The colour coding of route reference numbers is a great way of instantly selecting (or dismissing) climbs on any given sector. In this respect Rockfax seems to be approaching (if not already arrived at) perfection. Adding to this, the clarity of the crag shots where just about every pocket can be picked out... anything better could be entering the realm of 'virtual climbing' and I for one don't want anyone else doing my climbing for me, thank you....

Another very important feature is the inclusion of details of the definitive local guidebooks for each of the areas included in this book. These appear at the introduction to each section as thumbnails to give the reader an idea of what he or she is looking for. Details of a website where these topos can be found is also given. The statement in the general introduction clearly laying down clearly Rockfax's policy regarding not attempting to replace local guidebooks, and the inclusion of these local topos is especially welcome in pre-empting potential opposition from local climbers.

A notable omission is the translation of the introduction into French - there's one in German. I can only guess that the reasoning is to make it less attractive to French climbers and therefore protect the sales of their topos. However, an omission that I don't understand is that of what I thought to be a popular feature - the Top 50. Perhaps selecting 50 routes out of over 2000 was just too much of a daunting task...?

The action shots are particularly inspiring and cover all grades – not just the harder, maybe more spectacular routes. Happily an element of humour has been allowed in - check out page 177 as an example. Page 131 makes me want to go and do the route for its novelty value... and I just love Toby Dunn's concentration on page 183 - though don't think I'll be venturing on that...

I imagine Alan James suspected that Lofoten and Pembroke would be hard acts to follow, but Adrian Berry has certainly risen to the challenge. The result is just as stunning as everyone expects or, more correctly, demands from Rockfax these days.

More Info:

- Title: France : Haute Provence

- Author: Adrian Berry

- Publisher: Rockfax

- No. of Pages: 288

- No. of Routes: 2500

- ISBN: 978 1 873341 27 8

-

Price: £24.95

Comments