The Thru Hiker

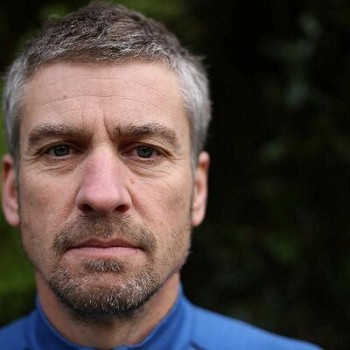

Physical activity is known to boost mental wellbeing, and it seems going for a simple walk is one of the best things you can do. In this series of articles we will speak to people who have found walking an effective response to issues with mental health - this week, walking writer Keith Foskett.

Also see:

- Walking for Mental Health: The Adversity Adventurer, with Alex Staniforth

- Walking for Mental Health, The Health Worker and ML, with Emma Holland

Author and hiker Keith, 50, comes from West Sussex, but has a passion for ultra-long-distance routes in wild places, most notably 'thru-hiking' classic trails of the US. In 2016, while suffering from severe depression, he set out to walk 600 miles through the length of Scotland. As recounted in his new book High and Low, this was as much a journey of self discovery as it was a long line on a map.

UKHillwalking: "My inner turmoil had nothing to do with any lack of passion for hiking" you write, in High and Low "or indeed unhappiness with decorating [for a living]. I was and had been suffering from depression for years. And I'd been completely oblivious to it." What made you realise?

Keith: My life since 2010 has, in the most part, been fun. I made a commitment to follow my dreams, namely thru-hiking crazy distances, and I was making a living writing about them. Let's face it, doing anything we love, and supporting ourselves through it, is a rewarding place to be.

However, my life was punctuated by bouts of unhappiness, low mood, lack of enthusiasm, and hopelessness. I first noticed this sadness on The Pacific Crest Trail in 2010, but it was infrequent, and didn't last. By 2016, when I hiked across Scotland, I battled it daily.

It took time, but the realisation dawned when I realised how much I had deteriorated, that each day was getting harder. Even then I believed it was just a low mood, that I'd snap out of it and it wasn't until I met a woman called Elina on The West Highland Way, who also suffered with depression and recognised I did too, that I realised.

Because the deterioration happened gradually over six years, on a daily basis I never noticed the slide. But suddenly, in Scotland, with much reflection, I realised how bad my situation had become.

I remember thinking that I wanted to push myself to the edge mentally to see what I was capable of. I certainly found out!

Can you describe your state of mind then - what were the psychological demons you mention in the book blurb?

My mind was just in turmoil. There were the symptoms I mentioned above, the fear of how I'd feel when I woke each morning, but also complete confusion as to why I felt the way I did. I referred to them as psychological demons because of the torment.

Those demons had the ability to make me sad, lethargic, unenthusiastic, helpless and many other things. I had two problems, the various negative feelings I experienced, and the frustration of not knowing why.

"Only when you immerse yourself in this physical journey will you begin to understand the psychological voyage" you say in the intro to High and Low. What do you mean by that?

The physical journey was the hike itself, and the psychological voyage was my mental state. I meant that to understand my mind, and my mental illness, the reader needed to come on the physical journey, which acted as the backdrop. It provided the setting going back to 2010, and the circumstances that emerged during the past few years

You chose to try walking the length of Scotland, from Cape Wrath to Kirk Yetholm, not long after serious health problems led to an evacuation from the Continental Divide Trail. What's more, you say you were relieved when you were forced to quit the CDT. That doesn't sound like the ideal build up to taking on several hundred kilometres through Scotland: what prompted you to do it?

I think it was part determination, part stubbornness, part ignorance, part refusal to believe what happened on the CDT, with some stupidity thrown in as well. I had to bail from the CDT because of pneumonia. The hospital ordered me to rest, which would take too long to consider carrying on that trail, so I decided to return to the UK and find another adventure once I'd recuperated.

What I couldn't figure out in the US was why I'd felt relieved to be off trail. Thru-hiking isn't cheap, it takes a lot of planning and dedication, and I love it. So, being forced off trail and waking up in a motel room after a day in hospital, and feeling relieved it was over, was confusing.

The prompt to hike across Scotland was partly to carry on my summer of hiking as planned, albeit in a different location, because, simply, I loved doing it. Also, I thought it might provide some head space to figure out my moods.

Lastly, hiking across Scotland had been a dream for years, so it just seemed a perfect time to do it.

Might there have been something about the size and extremity of the challenge that particularly appealed to your mental state at the time?

In terms of difficult hiking terrain, Scotland is over-qualified. I respected it because I was aware of its whims and moods, but even then, it caught me out. The terrain was harder than anticipated, especially at the start on the Cape Wrath Trail, and often there was no trail to follow at all. It was physically demanding, mentally exhausting (especially because of my depression), and the weather that year was atrocious.

I knew things could go one of two ways; I'd have an easier than expected hike, in glorious weather, with no mishaps. Or, everything that could test my resolve would, and it did.

It was the hardship prospect that appealed. I knew my head was in a bad place and I wanted to discover why. I could have flown somewhere else and attempted an easier hike in better conditions, but I wanted to test myself further.

I remember thinking that I wanted to push myself to the edge mentally to see what I was capable of. I certainly found out!

The daily walk helps clarify where I am and what I should be doing. It is time out.

It seems unlikely that anyone suffering mental ill health would find a miraculous cure in a single trip, however long. Aside from big trips, which can only ever be occasional, do you go out walking on a more regular, smaller scale basis? What role does that play for you in ongoing self-maintenance? (for want of a better term)

No, they wouldn't find a miraculous cure on one trip, unless they were aware they suffered with a mental illness. Then, they could use that time to at least initiate some form of understanding and healing.

I try and do some form of exercise every day, and usually that's a local walk for a couple of hours. My one failsafe apart from that is meditation. The first 30 minutes or so I do some thinking until my head is way too occupied and calling for some time out. Then I'll spend a good hour meditating. Meditation isn't about sitting cross-legged in front of a candle, it can be done pretty much anywhere. It clears my head, and I end up relaxed, focused, and calmer.

The daily walk is my escape, it helps clarify where I am and what I should be doing. It is time out.

Most of us would probably say that walking is beneficial to our mental as well as physical wellbeing. I guess the benefit stems from various things: It's well known for instance that exercise per se has positive neurological effects... But there's a lot more to walking than the physical exercise. In your experience, what psychological or emotional boost does going out for a walk in nature give you beyond the more prosaic benefit you might find in spending hours on an exercise bike?

Apart from the meditation, being outdoors has many benefits. I go to the gym occasionally but that is purely a physical experience, albeit with a post emotional high.

Being outside, I also have fresh air, sunlight, both of which are great for relieving depression. I also enjoy the quiet, it helps me to relax.

In my PCT memoir, The Last Englishman, I wrote about the wilderness versus civilisation effect. Most of us live in urban areas now, it's how our world is organised. But in the past we were, essentially, wild animals. Outdoors, whether it be mountains, desert, forest, or wherever, I believe is where we feel most comfortable.

That primeval instinct may be suppressed in most of us, but I don't believe we've forgotten thousands of years spent in the wild. That is where I believe our minds feel at home so to get outdoors reminds us of that time.

Do you walk to escape, or to find something?

Many reasons, but escape is a big part. In my twenties, I travelled because I genuinely thought I'd discover what I was doing in this world. As crazy as it sounds, I often thought I'd reach a day where everything suddenly became clear, the meaning of life if you like!

I know better now of course and yes, walking is my escape. It does provide time to think and find answers though.

The key is the head emptying. Up until that point I can be stressed because of the need to address my issues. Once I've meditated I relax, breathe, and look around at nature, feel the sun and immerse myself in the countryside

Why do you prefer to walk solo? Is the contemplative, introspective side of it important to you getting the most out of the experience?

I'm an introvert by nature. I used to say you'd find me in the kitchen at parties. Then, over time, it was the cupboard in the kitchen. Now, I don't even go!

I don't crave company and am perfectly happy in my own space for hours, even days. Most of my thru-hikes have been solo, although I met and walked with others. Basically, I just prefer hiking on my own and yes, I enjoy the contemplation that escape provides. I'm also free to do my own thing, I can hike however far I wish, camp wherever I want, sleep and wake up when I feel I want to.

I also think thru-hiking with someone else can be a bad idea because I've seen it break friendships and relationships. Hikers set off and suddenly realise that they have to spend 24 hours every day for several months with the same person. I'm not saying it can't be done, but often it doesn't work.

Is spending so long in your own company always a positive thing for you, or have there been times when it might have been less beneficial?

The majority of the time it's a positive. I can go for days, probably weeks without company, and revel in it. Simply, I just enjoy solitude.

The advantage of thru-hiking is that I can socialise when I need to. In 2010 when I hiked the Pacific Crest Trail, and 2012 when I did the Appalachian Trail, there were fewer people on the trail. In fact, that year on the PCT I think there were just over 200 registered thru-hikers. That's not a lot but they were condensed down to a space of two weeks at the end of April when most of us left, so there were many others I met, and hung out with. The AT is far busier, in fact in 2012 there were 3500 thousand registrations.

With thru-hiking I have the best of both worlds. I can plunge into solitude and when, or if, that gets too much, I have people around who I can enjoy being with too.

Imagine you're on a downer, and decide to head for the hills. Can you describe the psychological process of going for a walk: what changes in yourself and your mood do you experience as you go through the journey?

First ten minutes I walk to warm up to a comfortable temperature. Then I roll around what's going on in my life at that point and focus on the areas that need attention. Sometimes I'll find answers, but if I can't, I don't push it, and tuck that particular problem away to come back to. I do this for about 30 minutes and then I meditate to empty my head of all these things that demand my attention, and then enjoy an hour or so of walking without the pressure of finding answers, I try and forget everything and clear my mind.

The key is the head emptying. Up until that point I can be stressed because of the need to address my issues. Once I've meditated I relax, breathe, and look around at nature, feel the sun and immerse myself in the countryside.

My hike that year through Scotland didn't cure me, but it did provide the space for me to think, and realise I had to do something

Being out in nature, concentrating on the moment, meeting the basic demands of weather, navigation, staying safe and comfortable - going out on a walk, particularly a long one, seems to strip away the unnecessary and focus you in on these simple essentials. Is that part of the appeal, for you, and if so can you explain why it's beneficial?

There are many aspects to deal with on a long hike as you say such as navigation, weather etc. But, essentially life is stripped down to those fundamental, raw necessities. Important as they are, they don't take up much time and life on the trail is simplified somewhat.

The benefit for me is de-cluttering the mind and focusing on things we don't get the chance to otherwise. I find much of my thinking time at home is done when I'm falling asleep, which is never enough time. So, to suddenly have so much more time to think means I can delve into subjects to a greater depth.

An example: On the Appalachian Trail I thought and wrote about the rain. Not a topic that usually demands attention but with little to do other than concentrate on where I was walking, suddenly I could dive into those thoughts. For fun, I studied the frequency, ferocity, temperature and other elements of the rain. I learnt how the wind increased a certain way suggesting rain was imminent, often the trees alerted me by rustling, or swaying. I noticed how the wildlife quietened when a storm was coming, and after, slowly, how everything came back to life. The birds started singing again, the insects came back out, and rabbits came back to play.

I suppose the benefit is exercising the mind by delving into these subjects with such depth. As much as pushing weights up the gym builds and tones muscle, so does thinking time build a stronger mind, and with few distractions such as social media, life is stripped down.

Most long distance walkers and hillwalkers would probably agree that stepping away from the daily routine helps give them emotional and psychological perspective. Out on the hills you are a small human in a very big world, after all. Do you find that helps you put worries in their proper place and see the big picture more clearly?

In my PCT book, The Last Englishman, I wrote about viewing my life back home from the trail. Almost as though there were two of me, as I hiked I could picture myself back in the UK, working, playing, or whatever, like watching a movie.

Suddenly I began to realise where I was making mistakes, and how I could correct them. In fact, it was on the PCT, when indulging in such thoughts, that I realised I should hike more, and that I could possibly make a living as a writer. I was so tied up in my busy life before, that I never took the chance to step back and see if decorating (my previous profession) was what I actually wanted to do, and it wasn't.

So yes, I did see the bigger picture and it helped to address my worries, and provided the courage to address them.

Why was it important to you not only to walk for your own benefit, but to help encourage others through writing High and Low?

When I started writing High and Low I had no intention of writing about my depression, in fact at times I was ashamed of it, concerned what others might think. The more I researched mental illness I found that not talking about it was a large part of the problem. There is a stigma still attached, and it's hard to admit you have depression for fear of what others might think, and it is misunderstood.

About three chapters in, I began to think that I could help others with depression. Not just through walking but other methods as well, which I list in High and Low. If I'd struggled to find out what was wrong with me, why it happened, and what I could do about it, and if mental illness was as common as I thought, then I began to think I could offer help and advice to others.

One of the biggest lessons I learnt was to open up to people and tell them I suffered with depression, and not be concerned what they might think. It quickly became clear that a lot of people I knew also had mental health issues but kept them under wraps for the same reasons.

There are many things to help with depression, some of those way more important than walking. After all, my hike that year through Scotland didn't cure me, but it did provide the space for me to think, and realise I had to do something.

Walking provides time to leave life's clutter behind and focus on ourselves, which in turn could well offer an escape route, and initiate a healing process.

What walking-based advice would you offer someone who is suffering poor mental health?

Just go and do it!

Walking is easy, most of us can do it to varying levels. Perhaps you can only manage 10 minutes, others can walk all day. But, the more you do, as with most physical activity, the better you become, the fitter your body gets, and the easier it is.

I'd say just start with a distance that is comfortable and build up slowly. Try and spare an hour every day, and maybe half a day or more at the weekend when you become stronger. I've seen and read accounts on social media from people who began walking and struggled to go for five minutes. They persevered and a year later they were thru-hiking 2000 plus miles with a pack.

Research meditation as well and try to practice when walking. It can be difficult to clear the mind at first because we all have thoughts that regularly jump in and demand our attention. The trick is not to try and block those thoughts, simply to acknowledge them and move them away.

And whenever possible, try to walk away from town. There are fewer distractions, less noise, less pollution and the countryside is just more beneficial.