Tales of climbing and mountaineering adventures have long been written, read and shared; stories of fleeting moments of fear, survival epics and questing on peaks unconquered. Our rich heritage of mountain literature has inspired climbers and writers of today to continue documenting experiences in the outdoors; extractions from the quotidian that often encourage us to reflect on life as we sharpen our political or philosophical beliefs and calibrate our moral compass.

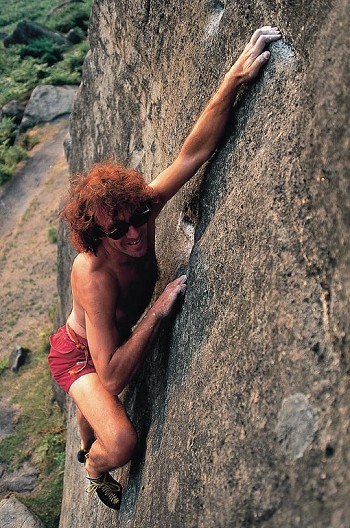

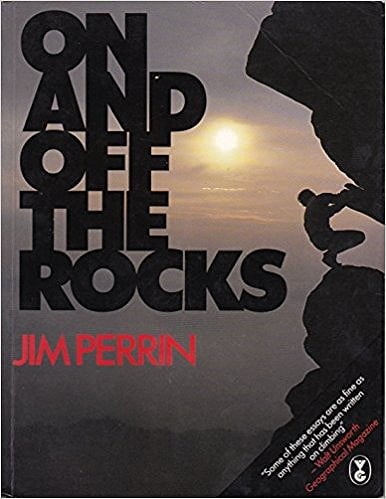

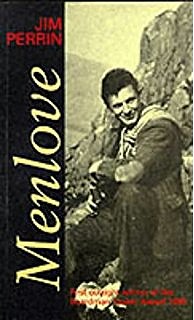

Jim Perrin is one of the most prominent writers in British climbing. A double Boardman Tasker winner with Menlove (1985), his biography of John Menlove Edwards and The Villain (2005), a biography of Don Whillans, Jim has a particular interest in the lives of others and the history of climbing and mountaineering. A talented and bold climber in his heyday with numerous first ascents and solos to his name, Jim's observations and ruminations on climbing experiences, environmental issues and travelling have made their way into his acclaimed essay collections - The Games Climbers Play and On and off the Rocks to name but a few - alongside his numerous contributions to newspaper columns in the mainstream media. Now aged 69 and living in the Ariège region of France, Jim kindly took the time to respond to some questions...

'Books and rocks were the companions and teachers, the dancing masters of my childhood and youth.' - Yes, to Dance

You mention in Yes, to Dance that your grandfather taught you to read, or helped you. Tell us about his 'eccentric education of you', which books or texts were you exposed to? Can you remember the first book you read?

This will sound completely bizarre to a contemporary reader, but the books from which my grandfather taught me to read, when I was three, were Pilgrim’s Progress and the Authorized Version. Some might think that explains a lot about my writing. They were the only books in the house apart from Pear’s Cyclopaedia and annual copies of Old Moore’s Almanack. My grandmother was illiterate, but enjoyed being read to. She and my grandfather were old country people transplanted to the city, and full of stories and superstitions. They believed in fairies, and so do I.

'Books and rocks were the companions and teachers, the dancing masters of my childhood and youth.' Did you read books with an interest in writing from a young age, or did that come later?

It came pretty soon. At Junior School I was always the one who had to read out his stories, which is good training – reading aloud trains your ear to the rhythms and metrical structures of prose.

What was the first mountaineering or climbing book that you read and which is your all-time favourite? (and why?)

The first two I read were Paddy Monkhouse’s On Foot in the Peak, which I found when I was twelve in the second-hand bookshop at the bottom of John Dalton Street in Manchester – the proprietor, who took me under his wing and directed my early reading, knew Monkhouse, who was northern editor of the Manchester Guardian. I ended up becoming very friendly with Paddy’s wife, and writing his obituary for The Guardian, as it had become. His two On Foot books are about hill-walking, and very good of their kind. The first climbing books I read were John Barford’s Climbing in Britain, Colin Kirkus’s Let’s Go Climbing, and John Disley’s Tackle Climbing This Way. Barford’s and Disley’s were both instruction books – I remember a photo of the 20-ft wall on Slape that fired my imagination, and Barford solemnly informed me that tricouni-nailed boots were the must-have. For those you went to the old Ellis Brigham’s shop in Ancoats, just by Ardwick Green. He’d been a cobbler, and it still had that atmosphere of leather and glue, as well as the very distinctive smell of hemp rope, which was still sold but definitely on the way out by then. You fished around in a big cardboard box and assembled a handful of the nails you wanted. Then you tacked the tricounis and clinkers into the welts, and star muggers into the soles, of plain leather boots bought from Timpson’s. They certainly did wonders for your technique.

I remember doing the Munich Climb in mine, and on those thin moves round the nose before Teufel’s Crack feeling very ill-at-ease. Fortunately I was in the middle of the rope between Arthur Williams and Brian Royle. But nailed boots were useless on grit, which was my first love, so I gave up on them quite soon, as did most other people, though Denny Moorhouse was still using them in the mid-1960s – he took a huge flyer off The Gates and they were so heavy they must have added something to his terminal velocity. The Aberdonian climbers were still using them in the 1970s for winter routes in the Cairngorms, and swore by them. The Kirkus book had an enormous influence on me, and I still love the freshness and simplicity of his climbing descriptions. That got me into trouble as well. You read the description of Great Central Route on Dow, check the guide and find it’s only VS. Then you get on it and think, “not in any sense that I recognize!” Grades in Wales were so much easier than in The Lakes or Scotland at that time.

I read in Welsh, as well as in French and German, but there’s a rhythm to thought that comes out in your writing, and mine was calibrated in those early lessons of my grandfather’s to seventeenth-century English prose. So I stick with that for creativity and expression, and just use Welsh – which I love as a language – for more everyday communication.

What is your all-time favourite non-climbing book, and why?

Impossible question! Montaigne’s Essais; King Lear; Little Dorrit; both parts of Goethe’s Faust; Der Schimmelreiter; Yeats’s poems; The Woodlanders for the texture of its prose; The Princess Casamassima; Thoreau’s Journals; Synge’s The Aran Islands; Hannah Arendt’s On Revolution; Simone Weil’s Waiting on God; Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy; Camus’s writings on north Africa; Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde; Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; Mansfield Park; Reich’s Die Massenpsychologie des Faschismus; The Old Wives’ Tale; Henry Wiliamson’s Flax of Dream tetralogy; anything by W.H. Hudson; Richard Jefferies’ last essays…They’d all be contenders, among thousands more.

I chose The Aran Islands when I was on Radio Four’s A Good Read a few years ago. Actually you’re given a shortlist to choose from so I took the Synge and my fellow panelist, Marina Warner, went for Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths, whilst the presenter, Sara Lefanu, opted for one of those airport bricks by Maeve Binchy – Evening Class, which we both had to read. It was dire, and when it came to the point where that was under discussion, we tore it to pieces, having been very polite and enthusiastic about each others’ choices. Sara had booked a table for lunch at a Clifton restaurant (the programme’s recorded in Bristol). When we’d finished recording she told us she wouldn’t be joining us, brusquely informed us that the BBC had an account there to which we could charge the bill, and to restrict ourselves to one bottle of wine each. I was delighted.

Fiction or non-fiction? Which do you find yourself reading more of?

Probably I don’t now read enough fiction – not many contemporary novelists appeal and some of the popular ones I find completely antipathetic. Ian McEwan, for example, turns my stomach. Apart from fiction I read a lot of poetry, plenty of nature and environmental books, and also biographies. I’ve just finished reading for the second time Ian Kershaw’s monumental two-volume biography of Hitler – very salutary in the current political context. If Brexit goes through, in twenty years’ time some historian will produce Theresa May and the Triumph of the Will: A Twenty-first Century National Tragedy.

That’s simple – the understanding imparted when a biographer truly engages with a subject. That’s what I enjoy about writing them. You’ll often find perceptions challenged, too, and that’s all to the good if soundly argued and justified by the facts.

Robert Macfarlane claimed that as a writer, you are 'closest in temperament' to WH Murray in the introduction to The Climbing Essays. Would you agree? How much has Murray's work influenced your writing?

If Robber Macpurloin said that, he must have borrowed it from somewhere. As to Bill Murray, he was very supportive and encouraging to me as a writer, and his own writing I’ve always admired. He so well conveys the atmosphere of activity among the Scottish mountains, and temperamentally I do feel kinship with his Romanticism. Others can do the sniggering. I’ll just revel in his roseate glows. Obviously, if you have an example like that before you, it gives you a sort of liberty…

Who else has inspired your writing from the world of mountain literature? Menlove Edwards must feature!

He does, as still by far the most subtle and acute of rock-climbing writers. But his own life-story transcends the writing, and has a kind of mythic grandeur. The way his phrases acted as counterpoint to my own activity on rock was pretty stimulating: “The mind made up, it only remained to go – not always an easy thing to do!” Said the voice in my head, time and again… It’s interesting to look back from more than thirty years now on the pressures that were working against me publishing that book. Despite abounding in closet gays, climbing at that time was profoundly homophobic, and my openness about Menlove was not unanimously approved, particularly among an older generation.

Who is your favourite non-climbing/mountaineering author?

Your question asks for the writer not the work, and the one to whom I feel most kinship is probably William Hazlitt, the great radical essayist.

How do you prefer to read - printed books or e-books?

Never read an e-book – why would I?

Do you devour books whole or dip in and out of a few?

Devour! Have done since I was a child. And I hold to the belief that wherever possible, a book – particularly a novel – should be read as nearly as possible at a sitting, so as to immerse yourself in its world.

You have contributed to various newspapers over the years, both in print and online on both climbing and environmental issues. Have you noticed any changes in the way mountain and climbing writing is received by the media and readers?

The way in which the activity’s evolved has modulated the manner in which it’s now read. The media has always, and still does, report it for the most part ignorantly and sensationally, but the way the climbing public responds to that is somehow less critical now. Though I’m thankful that the old anarchic attitudes of climbing can still break through to mock.

Two questions there: firstly, the essay had a long and honourable tradition in mountain writing, coming down through classics like Leslie Stephens’ The Playground of Europe through distinguished contributions to the major club journals to the present day, when it still exists under the careful patronage of editors like David Pickford and Katie Ives. The essay does seem to suit the nature of climbing experience, much of which is intense but brief, as a good essay should be. Secondly, the nature of contemporary online is instant, cut-and-thrust response as opposed to the essay’s more meditative dialectical structures around events. I do read some website material, and am often left feeling that a good editor would have come in handy. But that’s not the nature of the web. On why I wrote so many, for over thirty years I was writing monthly columns in one or other of the magazines, and they’re ideally of essay length at 2,000 words or so.

How often do you read out of your comfort zone?

I don’t read for comfort, but for information, entertainment, challenge.

To what extent does your day-to-day reading influence your own writing? (non-climbing literature specifically)

Continually you quest for parallels to your own experience, in order the better to apprehend its place in the whole.

Which book on your shelf would surprise or shock us the most?

The Koran..?

What are you currently reading?

I just finished re-reading Moby Dick this morning, for the first time in fifty years. The dark, doom-laden nature of its narrative has left me quite shocked. I wonder what instinct brought me back to it at this political juncture, with fascists – and make no mistake, they fulfil every requirement of the definition – in power here and in America, and the threat of them also succeeding in France, where I now live?

Of course not. The act is always supreme, and now that my body is no longer capable of its easy accomplishment, I hold to the memory of it, and celebrate that in all its implications and resonances.

In which direction do you think mountain literature is heading? What do you think people want to read about in climbing and mountaineering these days?

They’ve always wanted to read about success, which in many ways is the least interesting aspect of climbing; or failing that, of disaster, which is plain prurience. What worries me about the direction of some climbing writing is its take-over by products of the “creative writing” academies, who see the activity as fit subject matter for annexation, regardless of how slender their experience of it is. You have to do it, live it, first, before you’ll have anything significant to say. Though those of the Stanford and Cambridge schools might not agree.

Environmental writing could be considered one of the most important themes of today. What do you hope to achieve through writing on this topic? Are people reading, and are they listening?

Awareness of the detail of what’s happening, and the drift towards the extinction of planetary life in all its multiplicity. People are reading and listening, but also much is fed into the echo-chambers of social media, and its import, urgency and clarity are thereby lost.

Which climbing or mountaineering biography(ies!) have you enjoyed the most and why?

It’s not really a biography, or even a comprehensive autobiography, though it has elements of each, but Simon McCartney’s The Bond seems to me perhaps the finest mountain narrative ever written, absolutely rooted in all the finest values of our activity. I took Joe Brown a copy recently, and his view was that he’d never read a better climbing book. I agree.

Which climbing/mountaineering book should be adapted into a film that hasn't yet been?

Arlene Blum’s A Woman’s Place – fascinating psychodynamics, and an all-woman cast!

If you could invite two climbing/mountaineering authors to dinner...dead or alive, who would they be and why?

Al Harris and Alex MacIntyre, because they were good friends and I miss them both. And if we can squeeze two more in, Dave Cook, who was my political mentor as well as a frequent climbing companion, and T.I.M. Lewis – four of the best playmates I ever had!

Desert island books - pick eight (or however many are significant) books that give an overview of your life with a short sentence describing why each one was important at each stage. Which one would you take to a desert island?

George Borrow – Wild Wales

For its bizarre and teasing authorial persona, and the vast enthusiasm for his subject. Important in establishing my knowledge and relationship with Wales, which was long my home.

Jonathan Swift – Gulliver’s Travels

For its grotesqueries, and the political satire – vital in developing healthy scepticism.

Henry Williamson – Tarka the Otter

For the vital sense of natural life and the rewards of close observation, but also for the odd and disturbing sense that this is as much war book as nature narrative, and clamorous with the echoes of Williamson’s own Great War experiences.

The Mabinogion

For the dimensions of magic, and the sense of how story comes to root in physical landscapes.

Paradise Lost

Those sonorous, rolling periods of Milton’s, the demonic characterisations that are so psychologically astute, and his sympathy for the devil who inhabits all of us! (You need a screech mark after Milton!)

Boswell’s Life of Johnson

Not just for the gigantic yet intimate portrait of subject, fascinating though he is, but for the deft and inconspicuous techniques of the author, who succeeded through them in inventing the modern genre of life-writing.

Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit

In which the lively imagination of the novelist presents to us the many ways in which life itself is bound up in the enclosing symbol of the prison – from which escape may be made.

W.B. Yeats, Collected Poems

Because Yeats, most musical of poets (and a great sham and poseur, of course), gives us the clearest sense of his own emotional life, which builds into one of the most moving engagements with the process of ageing in any literature – a theme of interest to me now that I am on the very brink of my three-score-and-ten.

Ok, you can take a luxury item too...what would that be?

My cat, because she’s the most luxurious creature on this planet; and my little Parson Russell Terrier too, please, because my dear buddy Paul Ross gave her to me at a particularly difficult juncture in life ten years ago “to stop me moping”. He’s a good, wise man, Paul, and one of the great climbers of his generation!

What's next on your reading list?

Peter Riley’s The Derbyshire Poems, because it looks interesting and I want to see how it works. Beyond that, who knows?

And what’s your favourite climbing book?

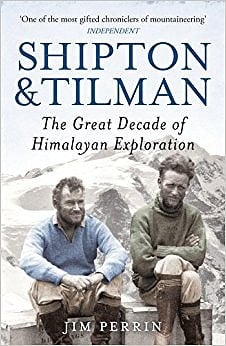

Eric Shipton's Nanda Devi, which recounts the 1934 reconnaissances in Garhwal and first entry into the Nanda Devi Sanctuary with H.W. Tilman and a remarkable trio of Sherpas (including the one many claim as greatest of them all, Ang Tharkay, who's memorably portrayed by Shipton). It's one of the great mountaineering adventure stories, and by a Himalayan mile the best of Shipton's books. (Interestingly, it was the only one that his lover, Pamela Freston, didn't get to edit substantially.) I used to think that H.W. Tilman was the better mountain writer, and his suave, literary, ironical style still appeals. But the simplicity, the wryness, the sly depiction of Tilman's character, the resourcefulness and sense of fun and seat-of-your-pants adventuring, the romantic lushness of response in Nanda Devi soar beyond anything Tilman achieved in his writing. It's one of the strange, mystical masterpieces of our literature, and I read it time and again for its sense of hardy joy in mountain activity and exploration.

When I set out in climbing, both Shipton and Tilman’s stars had faded rather as mountain writers. If I’m pleased about anything I’ve achieved in the field of climbing literature, it’s having kept their reputations extant and maybe even enhanced over the last 30-odd years since the two compendium volumes of their mountain travel books which I edited came out from Diadem.

After I first suggested the project to Ken Wilson, he and I rowed furiously over who we should run first. I was for Tilman, who I knew, and whose style better suited the literary snob I then was. Ken wanted to go with Shipton, whose books are much more uneven, repetitive and at times badly edited. But at his best he’s incomparable, and the finer of the two. So I have to say to Ken that in retrospect he was probably right. Pity he’s not still around to hear me. He was an interesting old bastard, that one!

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Spectacular Sights at Great Height - Visual Phenomena in the Mountains 27 Mar, 2023

- ARTICLE: Using OpenAI to Create Climbing Content and Images 27 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: COP27 and the Cryosphere - No Mountaintop Miracles 11 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Coronation Coincidence: Everest 1953 and Queen Elizabeth II 13 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Meet Ralph, the First Canine Compleatist of the Grahams 4 Aug, 2022

- ARTICLE: Climbers and Guides Adapt to Changing Climate and Landscape in the Alps 28 Jul, 2022

- ARTICLE: Earth Day 2022: Climate Change and Mountains - The Latest Science 22 Apr, 2022

Comments