This project is supported by Arts Council England, The Wordsworth Trust, and the Friends of the Lake District.

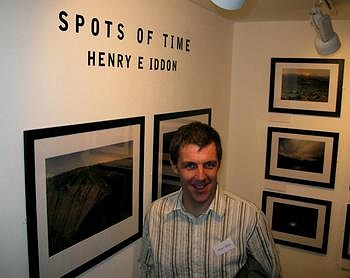

Henry's book Spots of Time, The Lake District photographed by night, was published by the Wordsworth Trust on the occaision of the exhibition Spots of Time, 16 March 2008, in an edition of 800 copies. Website: www.spots-of-time.co.uk

Spots of Time, the exhibition, is running at The Trust's 3°W Gallery, at Dove Cottage, Grasmere, until September 2008 and it is FREE to visit. You can purchase the book Spots of Time at the exhibition or online. Details at this page Wordsworth Trust. The Wordsworth Trust is ideally situated to visit when on a climbing trip to the Lake District.

You can read Natural Magic and Moonlight a commentary on Spots of Time by Paul Hill MBE, Professor of Photography, here at UKClimbing.com.

In this essay, Spots of Time: The Experience Henry describes some of his experiences when photographing the Lake District at night.

Spots of Time: The Experience by Henry Iddon

Images of landscapes have been mediated through photography for over 150 years. During this period the different types of landscape photography have become as varied as the terrain and agendas they map out. Much of this work has been produced during the day time. The night-time imagery that has been produced to a stated context often concerns itself with easily accessible urban spaces. My intention was to produce a cohesive body of work that considered the vast landscape of the Lake District at night. This work was centred around the themes and philosophies of Wordsworth and the Romantics, being a technical, physical and intellectual challenge. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries the arts shifted from a reasoned approach to one which considered emotion and imagination. Wordsworth and Coleridge were among the first British Poets to explore these ideas, and they did so in the peaceful surrounds of the Lake District. There they were able to ponder the relationship between nature and human life, explore the power of the imagination, reflect upon the mythological, fantastical, gothic and supernatural. There was an emphasis on the sublime - a spiritual awareness that could be stimulated by a grand and awesome landscape. At this time the Lake District was a relatively remote and peaceful area, but with the huge number of visitors today the only time when it's possible to experience anything like the 'peace' of Wordsworth's time is in the dead of night.

I hope that when people view the images produced they understand the taking of them to be a lived experience, not simply photographs that someone took. I had to be there to record what was happening, and therefore experience being in the mountains at night and in darkness numerous times. As humans we are adapted to perform at our best in sunlit conditions, and are rather poorly equipped to function in darkness. Not surprisingly therefore we have found ways of keeping darkness at bay and illuminating our night-time world: fire, candles, gas lamps and the electric light bulb. But without these manufactured sources of illumination we have to make do with the light of the moon, and as this is insufficient we draw on our other senses – auditory, olfactory and tactile. Our senses become heightened, particularly our vision.

The human eye has two types of photo-receptive cells: rods and cones. Cone cells are responsible for our acute vision and colour perception, and are clustered in the central part of the retina. They work well under bright light. Rod cells are found further out to the edges of the retina, and the eye switches to them when light levels drop. During 1979 three scientists, Lamb, Baylor and Yau proved that a rod cell could be activated by a single photon. This is maximised during periods of low light intensity by the body's production of a photosensitive chemical called rhodopsin, which builds up in the rod cells in a process called dark adaptation. It can take up to two hours for the eye to be fully adapted to the dark. And while they may function well in low light, rod cells do not perceive colour – only white, black and greyscale. Because of this the world at night is drained of colour.

One of the more common situations is the simple fact that I have had the whole of the national park's summits to myself – it is hard to describe the sense of wonder that being alone and having ownership of the Cumbrian mountains all to yourself brings. Suddenly one of the most visited areas of the United Kingdom becomes a secret garden, rarely seen by the thousands of tourists. Throughout the night it has belonged to me, before handing it back to the masses in the morning.

For practical reasons my visits have coincided with periods of settled weather around the full moon. Mountain areas often don't follow the prescribed forecast and on at least two occasions I have found myself at the wrath of the wind and rain. There are upsides to being saddled with a huge rucksack, full of photographic equipment and camping paraphernalia, while being buffeted by wind and heavy rain. In the hope a window of clear weather, myself and two companions headed to High Street above Haweswater. As we ascended Heron Crag above the reservoir, clouds began to gather above Nan Bield pass, the evening light adding a sinister golden hue to the leaden sky. A herd of deer dashed across the path above Blea water, sensing the storm and no doubt looking for shelter. By the plateau of Racecourse Hill it was obvious that a late rising moon, high winds and impeding deluge meant no photographs would be taken. Rain would stop play. We headed down towards Small Water, and as we did so the clouds parted briefly to reveal a huge yellow full moon hung low in the sky. Gone. The enormous water filled clouds obscured the view, then it cleared again. We had three, maybe four glimpses of a children's storybook moon amongst the storm clouds. Big, yellow, majestic, awesome, sublime. A memory, too brief to be photographed, but too incredible to be forgotten.

Although thankfully the rain held off, a similar experience occurred between High Stile and High Crag, Buttermere. The moon was higher in the sky, and huge clouds were billowing up from Ennerdale, with occasional shafts of moonlight breaking through or back lighting the cumulus nimbus. The whole scene felt like you were in a Turner painting.

Interestingly, the height the moon appears in the sky varies– not only by season but also through an 18.6 year cycle. When on Great Gable in June 2006 the earth's only natural satellite appeared to barely pass over the Scafell range, it being at its lowest in the night sky since 1988. Conversely by Octobers 'harvest' moon as I walked across Maiden Moor towards Dale Head, the moon was as high as it would get before 2024.

The contrast in mountain weather was brought sharply into relief on Pillar at the start of 2007. Although the moon was only a waxing crescent at ten percent of full, there was snow on the ground. Recent mild weather encouraged me to head into the hills in case there was no more significant snow during the winter, even though I was eleven days off the full moon. The walk up Mosedale to Black Sail was uneventful, but above Wistow Crags the breeze increased to a stiff wind. By the summit the snow was being blown by gale force winds and the mercury had dropped significantly. On all my nocturnal wanderings the aim has been to sleep on or close to the final summit. With the strength of the wind and the snow covered rocky ground of Pillar unsuitable for tent pitching, we pressed on. Now Windy Gap has its name for a reason, however just above it is a small flat area, perfect for a tent. A room with a view. As it was now the following morning this was an opportunity to erect the tent, eat, and sleep. On this occasion I had a friend with me, and all hands were on deck as we changed the main sail on a maxi yacht rounding Cape Horn in a gale. Or at least that's how it felt erecting the night's accommodation.

It is easy to fall into the trap of over estimating the strength of the wind, but it must have been at least 40mph if not stronger, and well below zero. Windy Gap. Dawn was just after 8am, and perched as we were above the valley and looking across to a frozen Great Gable and Scafell, we had the best seats in the house for a winter sunrise. The colour changing all the time and being reflected by the snow and jewel encrusted grasses, the ribbon of Mosedale Beck just catching the light of the new day.

To wake and see something sublime is one thing, extremely rarely though you are gifted the opportunity to witness nature's magic at work. Having spent the previous night in the hills between Haweswater and Brothers Water, walking over 20 miles, and doing a piece for BBC TV in the afternoon around Grasmere, it was with heavy legs that I set off up Clough Head from Threlkeld at 10pm. The sky was clear and it was February's full moon. Perfect conditions. By 2am I had been on the summit a couple of hours and had taken several images of Keswick glowing below a starry sky, car lights streaked along the A66 and the frost on the fields that flank the rivers Greta and Glendermackin. As I dismantled the tripod, and turned towards the tent pitched by the cairn I noticed a band of low cloud drifting south from Bassenthwaite towards Derwent Water. I sat and marvelled as the town was covered by a yellow blanket, the stunning result of a temperature inversion and the staggering amount of light pollution that conurbations emit from domestic dwellings, retail outlets and street lighting. Bed and Breakfasts, hotels and hostels would be full of sleeping outdoor folk who would wake the following morning, breakfast and head to the hills in the hope of breaking through the cloud and walking the fells. Below them on their Sunday walk the misty vapour would hug the lower slopes with its chilly dampness. Yet I was able to pause from my work in the middle of the night and watch the magic unfold, and the scene be set, as the low cloud crept along the valley floors eventually leaving the fells as islands in a dark sea of cloud with only the stars above.

Another occasion when the project brought me in unusual contact with the natural world was while walking along Blea Rigg between Easdale and Langdale. It was around midnight, the start of a new day, and having stopped for some refreshment I suddenly noticed two eyes staring at me. They then vanished only to appear moments later a matter of twenty feet away when it became obvious that they belonged to a local resident – a fox. It must have been short of company on the fells that night as it then continued to follow for over a mile. During the project duration I have also spent time with the wild ponies of Kentmere, the herd of Galloway cattle introduced to Silver Cove, Ennerdale, and a badger near Ullswater.

Having spent over twenty nights walking the Lake District fells I have had many more memories and magical experiences, all amplified by the fact that they were unique, unusual, and even sublime. I would hope that the images in the exhibition and accompanying book allow the viewer a glimpse into some of my spots of time.

Images and text © Henry Iddon 2008

The exhibition Spots of Time runs from 16th March until September 2008 at the 3˚W Gallery, Wordsworth Museum, Grasmere, Cumbria, LA22 9SH and it is FREE to visit.

T: 015394 35544 E: enquires@wordsworth.org.uk

The exhibition catalogue features an introduction by Lord Chris Smith and an extended essay by Prof. Paul Hill.

www.wordsworth.org.uk

www.spots-of-time.co.uk

Images have been shown at; Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool; Photographers Gallery, London; Folly Gallery, Lancaster; Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool; Turton Tower, Bolton and The Oxo Tower, London. His work is also held in collections by Kendal Mountain Film Festival, Banff Centre for Mountain Culture (Canada), and The North West Film Archive (Manchester Metropolitan University).

His Master of Arts research document (at De Montfort University, Leicester) on Sport and the Athletic Experience was highly acclaimed in the UK and USA and has been described as the benchmark for further study. He has also developed and supported community arts initiatives for young people and adults; including working as an 'artist in residence' within a formal education setting, holding creative workshops for those on the fringes of society. Henry has also played a major role in the planning and implementation of pilot creative arts programmes for school leavers.

Henry Iddon contact details.

Fineline Photo

(+44) 07976 375013

henry.iddon@mac.com

henry@fineline.ph

www.fineline.ph

Comments