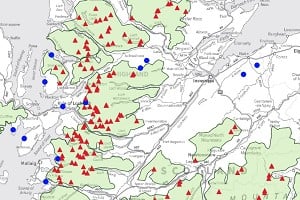

In May and June 2014 Londoner Stefan Durkacz walked a five-week lap of the River Tay watershed, a 457km solo backpacking route following the high ground over mountains, moors, forest and farmland. At almost 2000 km2 this is the largest river catchment in Scotland, its boundary forming a huge arc from Monifieth at the mouth of the Tay, through Angus, the Mounth, the Central and Southern Highlands and out along the Ochils to the beach at Tentsmuir Point in north east Fife. We reported on Stefan's walk at the beginning of July (see here); below is a more reflective account of the trip.

I was coming to my senses, but it was far too late for second thoughts. We were swaying and clattering out of north-east Fife and onto the railway bridge over the Tay. I was about to step off the train into a city I didn’t know very well, 450 miles away from home and family, and spend the next five weeks largely alone. I would be walking all day, almost every day, sleeping rough in a bivvy bag under a tarp. There would be rain, probably lots of it, and wind, and midges. At times I would need to navigate carefully with a map and compass despite being wet and cold and tired and despondent. Next morning I’d pull on clammy clothes and do the same again. If things went wrong, it would be down to me alone to sort them out.

Why was I doing this? For months I’d been obsessing about walking the 300 miles of the River Tay catchment boundary. The route appealed for a number of practical reasons, but in a way it was neither here nor there. I just wanted a long walk. If anyone had asked why, I might have talked about the personal challenge, because that's easy to do: peaks to climb, miles to walk, hardships to endure, with nature as a backdrop and barrier to my endeavours. But right then, I didn’t really know. The only way to find out was to start walking. Put myself in the way of experience, and stay committed.

"Backpacking: just for a while you sink into the landscape, you shrink a little while it grows"

Just over twenty-four hours later I got a powerful inkling of what this venture would really be about. Towards the end of the day, deep in the Angus countryside, I picked my way through gorse, nettles and long grass along a field margin where the map promised a track that the ground failed to deliver. Eventually I reached a main road, crossed it, and took a track into woods. A weathered sign warned of shooting in progress, but it was quiet and there were no fresh footprints or tyre treads. I pressed on. The track became grassed over, the stillness settled like a blanket. I felt, not quite like I was being watched, but that I'd been noticed.

I camped on a deep litter of leaves under some huge old beech trees. As it got dark I got a little blaze going in my wood-burning stove, placed safely on a flat rock. By the rock, a large earthworm emerged, pushing the leaves aside. It had sensed the heat and was fleeing. A timeless reaction, honed in primeval wildfires. I was falling through the brittle crust of self-centred expectation (challenge, adventure, achievement) into the unpredictable waters of experience and the beautiful, frightening currents of nature. Already the walk was taking me over.

Next day I plunged through that civilised crust again. I had lunch at the ruins of Restenneth Priory, founded by a Pictish king in AD745 and possibly a pagan place of worship long before that. When the priory was built it was on a promontory jutting out into a loch. Restenneth Loch is long gone; now it's Restenneth Moss. I needed to reach the village of Lunanhead on the far side.

"On the remotest stretch of the walk I narrowly missed being struck by lightning"

I followed a disused path down into the reed beds. The loch had made a slight return: I was soon wading knee-deep through water, with reeds six or seven feet high on either side. I probed ahead with my poles, checking the depth. It was humid and still; I had that strange feeling of being noticed again. There was a crash and witch's shriek to my left. I turned in time to see a heron labouring upwards, out of the reeds. A few minutes later I was walking through residential streets, by neat gardens and parked cars.

All this just a few miles outside Forfar – not quite where I expected to feel the wildness, but then again, wild things, being wild, don't recognise things like national park boundaries and nature reserves. Crossing the Angus lowlands turned out to be more than just a race to the 'good stuff' in the Highlands.

The walk, I realised, would be about encounters, about being a witness, and about simply being there as just one vulnerable living thing amongst others in the landscape. That vulnerability is real. Nature can kill you, even on this tame little island. On the remotest stretch of the walk I was caught in a thunderstorm on the exposed flank of Carn an Fhidleir and narrowly missed being struck by lightning. Helpless and out of options, I flipped into magical thinking and prayed for the first time in decades. I stayed calm and stayed put, just.

Less deadly but most striking were the many encounters with wildlife. I was mostly alone, mostly quiet, and I saw a lot. On a dry, overcast morning, a couple of days after being knocked off course by the lightning, I packed up camp in Glen Feshie and took a long track back up towards the plateau and Leathad an Taobhainn, a sprawling top on the watershed nearly 3000 feet high. Walking in a dwam I rounded a corner. Something huge flapped heavily off the track. A juvenile golden eagle, feathers flecked with white, passed me within a few feet. Its eye flicked back, holding my gaze. Then it was gone, swooping downhill before powering up high over the moors. I rushed over to where it had been on the track. There was the gory corpse of a hare. The muscle meat had been picked off, the unwanted entrails strewn across the ground amongst clumps of grey-white fluff.

I often saw things because I walked late and kept unsociable hours that day trippers to the hills generally cannot. Being outside all the time quickly became second nature. I slept well and didn't relish the occasional stuffy night indoors. Towards the last week of the walk, just after the weather had started getting really good, I had a late start after a rest day in Strathyre. No matter – it wouldn't get properly dark at all. The evening light was simultaneously dazzling and soft as I negotiated a steep slope past a jumble of massive boulders, remains of an old rock fall. I caught a movement out of the corner of my eye and turned quickly. Two fox cubs stood on the rocks, watching me. One after another they disappeared, swiftly and silently. Later, on Stuc a'Chroin, I shared the last light with a busy ring ouzel on the final climb to the summit. It felt like we were the only souls on the mountain.

"Something huge flapped heavily off the track. A juvenile golden eagle, feathers flecked with white, passed me within a few feet. Its eye flicked back, holding my gaze"

But these weren't the only encounters that mattered, thrilling as it is to be looked in the eye and sized up by something non-human. Scotland is a well-worn and thoroughly lived-in place, all over. There are wild places and wild land all around the Tay watershed, but no wilderness, in the pure sense. People and their works, old and new, are everywhere, and my walk was full of chance and memorable meetings. Away from the major trails like the West Highland Way, walking with a big rucksack and walking poles does get you noticed. People are still drawn to travellers on foot. Long distance backpacking might seem to be all about solitude or even loneliness to the uninitiated, but somehow the literal baggage I carried seemed to imply a lack of metaphorical baggage. Interactions with people were refreshing, upbeat and easy, and the glow sometimes lasted the whole day: quality, not quantity. It was nice to just be someone out for a walk, rather than an employer or employee or customer.

In our brave new globalised world it's terribly uncool to be too attached to a place. People the world over still have a stubborn tendency to love and feel connected to places, though. In upper Glen Lyon, around mid-morning after a camp of great solitude at the foot of Beinn a'Chreachain, I was sitting by the track adjusting my boots. I looked up and was surprised to see four people walking towards me: a local couple with two friends visiting from abroad. They were taking them to see the Tigh nam Bodach, the house of the old man, the ancient Celtic pagan shrine in Gleann Cailliche, glen of the old woman. I was going too, so I tagged along. The local man was grey-haired and spry with twinkling eyes. “We come in peace!” he called across to the little stone figures outside their house, tongue in cheek, for the benefit of their visitors. He explained what the shrine was, and each of the weathered stone figures standing outside – the bodach, the cailleach, and their children; and described how they were taken out of the little house at the turn of the season in April and returned in October, and the entrance to the house blocked up with stones.

We talked about these wild upper reaches of Glen Lyon and how they'd changed over the years. The current track was only ten years old. I'd been surprised to find it as it wasn't on my map. Much worse, though, was the plan to build a mini hydro scheme in Gleann Cailliche. If it went ahead it would surely spell the end for the Tigh nam Bodach. Aside from the construction of the scheme, the track would probably be widened to a haul road to accommodate heavy construction traffic and driven further into Gleann Cailliche. The shrine could be damaged, the figures stolen. Access would be easy, whereas ten years ago only the most determined would venture into trackless Gleann Cailliche. One of the oldest pagan rituals in Europe, an ancient link to nature and the land, would be finished. It appears the plan is on hold and Tigh nam Bodach is safe for now.

I walked beyond the end of the track and followed the Allt na Cailliche up and up, past countless pools and falls and rapids into its infancy. Near the bealach I turned left, following a little burn up the slope to where it emerged from under a great bank of old snow. I had a long drink. The water was so cold it nearly burned. There was a time when I thought that 'they' would never find an excuse to exploit places like this for money. Later, my route took me through two windfarms – Braes of Doune and Green Knowes in the Ochils. Walking through the industrial hum and clanking, overawed by the scale and ingenuity of the machines, it was clear that this is about saving our lifestyle and privilege, not saving the planet. Perhaps this is a doomed venture, the only relevant question being, how much of the natural world will we take down with us? Without witnesses getting out there and breaking through that thin civilised crust, without people to fight for it, who knows where it would end.

'Getting back to nature' sounds trite and cliched. It does mean something though, and backpacking, especially alone, is a great way to reconnect. The simplicity of it, using the oldest means of travel – your own feet – and carrying the minimum of equipment, promotes an uncluttered and receptive state of mind. It is travel at human speed.

Sometimes it seems that wild places are an itch we as a species can't help scratching to oblivion. Nature is always the first thing to be sacrificed to our dubious needs. It was difficult to walk the Tay catchment boundary and not notice the lack of value placed on wildness. But there was still much richness and diversity. On a long distance walk, especially if you stay outdoors to sleep, you can break through that crust of self-centred expectation and open yourself up to nature. Just for a while you sink into the landscape, you shrink a little while it grows. This is perspective, which is no bad thing.

I walked the Tay catchment boundary for two great charities, Scottish Wild Land Group and Venture Trust.

You can still sponsor me by making a donation to Scottish Wild Land Group here, and Venture Trust here.

Comments