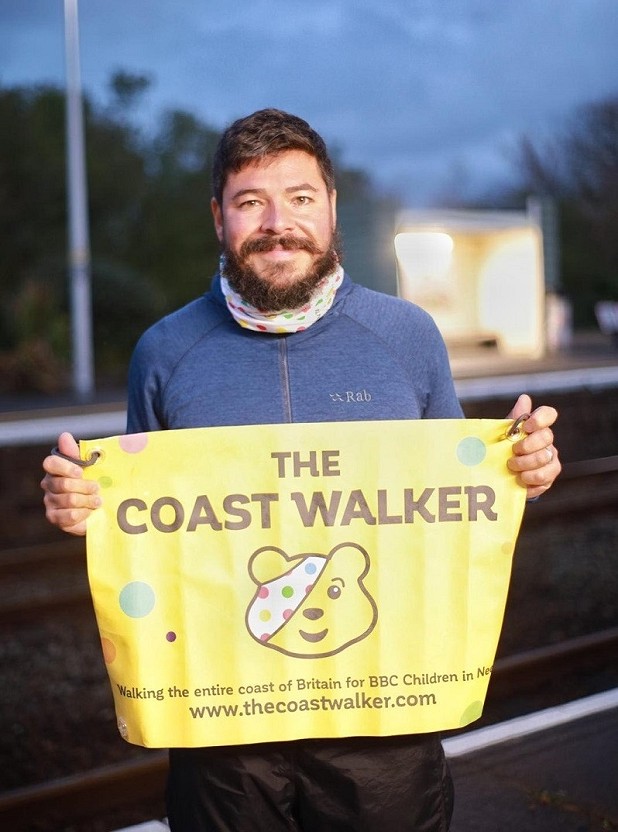

Between July 2020 and March 2022 Chris Howard spent most days on his feet, taking on a walk of more than 11,000 miles around the coastline of Great Britain. As if that weren't enough, he climbed the three national high points in passing, added the wiggly outline of Skye to his route, and raised a huge sum for Children in Need. Chris, 37, who when he's not out and about co-runs a construction company with his wife, has made a number of adventurous journeys, fundraising for children's and environmental charities along the way. Was this the hardest trip to date? From sandy beaches to concrete promenades, industrial wastelands to remote clifftops, what did it take to hike Britain's convoluted shoreline, largely solo, in all weathers and seasons, and averaging a Marathon a day? We caught up with him to find out.

UKHillwalking: From this trip alone you've raised over £41,000 to date. Why did you pick Children in Need?

Chris: I chose Children in Need because 96p in every pound goes straight to a child, and because we often don't think of children in the UK being in bad situations or deprived areas. There are parts of the UK that you can't imagine how they exist, and they shouldn't. Children should not be suffering, they should be encouraged, guided, nurtured, loved, inspired, as well as fed, clothed, washed and taken care of.

Some days I was on concrete promenade, the next scrambling over seaweed and rocks, climbing round cliffs, walking the clifftops

Have you got a precise figure for how far you walked?

I worked out my route with OS and the British cartographical society, including the peaks and islands attached by bridge or tidal causeway. Walking home from Norfolk to Cambridge along the river Ouse was exactly 11,087 miles so the following day I ran the Cambridge half marathon with my backpack to round it up to 11,100… glutton for punishment I know, but the 87 would have niggled at me!

Britain's coast is more wiggly than most, and I guess it is by a huge margin the longest logical walk you can do in the UK. What inspired you to take on this particular journey?

Actually it was my children that inspired the walk. I was watching them play in the garden during the first lockdown and realised how lucky they were by comparison to a lot of kids in the UK. I wanted to do something for children who were suffering and try to create a bit of hope out of the pandemic. One of the first things I read on the BBC Children In Need website was 'reaching children in every corner of the UK' that fitted nicely and was also a way to reach a big number of children that I could directly impact.

How much forward planning and research went into it?

Well actually not as much as you'd think: I came up with the idea and left three weeks later! I wrote a website, set up a Justgiving page and packed and repacked my bag about 100 times to cut out anything I didn't need, then I left and thought I'd just have to get on with it. If I started planning the whole thing I probably would have talked myself out of it.

My aim was to walk a marathon a day no matter how long that took

How about physical training? I assume this wasn't the sort of trip just anyone could get up and do from a sitting start?

I mean I've always been pretty fit and active and in fact lockdown meant I was probably a bit heavier than I had been for a long time, but the idea of training to walk anywhere always makes me laugh - flippantly I sort of inwardly snigger and think "well I guess I learnt to walk at around the age of two and I've been doing it ever since". But yes it's a tricky one as carrying weight and walking long distance is actually what we're designed to do as humans, we just don't do it as much anymore. When I left I'd not walked anywhere for more than an hour in months due to the Coronavirus restrictions. It's amazing how quickly the body adapts though.

Have there been many other round-the-coast walkers, and if so were you able to contact any of them for advice?

I think there have been less than 40 officially, but they all approach it differently, many over years on and off. I wanted a full consecutive trip and to get round in one go. I didn't really seek advice, but I did ask to be out on the official list which I was. Then a guy that was starting his walk after me got in touch and we messaged each other every single day. He started further north than me and I eventually caught up to him on the east coast of Scotland and we met in person having been speaking every day for over a year! We've become great friends. I recently visited him in Kent where's he's still currently walking.

Did you have a route fully mapped out in advance, or was it a case of improvising as you go?

Absolutely improvised. I had it in mind that I'd stick as close to the water's edge as I reasonably could depending on tide. Some days I was on concrete promenade, the next scrambling over seaweed and rocks, climbing round cliffs, walking the clifftops. Then obviously there were estuaries and rivers too.

You spent much of the autumn and winter just gone walking around Scotland. Weather-wise this has to be the most challenging part of the country at the toughest time of year. If you did it again (hypothetically, you understand) would you be inclined to time that differently?

The great thing about walking the beach itself is you can go barefoot and cool your feet!

I had planned to get to Scotland in February, avoiding the midges on the west coast and walking towards the longer, brighter, warmer days, but due to the Welsh lockdown things shifted and I just continued as I could. I actually learnt to love the Scottish winter because it's a proper winter. Very cold, regularly waking up with snow on me, walking in the snow, frozen lochs, short days and just an amazingly different experience. I always think you can't worry about the things you can't control so just get on and worry about the things you can control.

It's been a strange couple of years for all of us thanks to the pandemic, but you took self isolation to a higher level than most! How did the pandemic affect your experience of the journey?

It was very interesting, I'd get treated differently everywhere. Often if I did see anyone I was told I shouldn't be on holiday in their area (I wasn't really on holiday but always remained polite). Some people were fascinated as they'd never met anyone doing what I was doing and a lot of people were incredibly kind, feeding me, offering me places to stay etc. I think things would have been different pre pandemic. It has made us more curious, and possibly less judgemental for most too.

I had a period of 4.5 months in lockdown in Wales which although frustrating allowed me a bit of time to work on the challenge from another perspective. I gave talks online to scout groups and schools, and I stared writing and doing podcast interviews which really helped promote what I was trying to achieve.

Walking so far, for so long, there must have been low points. Did you ever feel like quitting, or question why you were there? How did you maintain motivation at low moments?

Yes, almost weekly and daily at points. It gets very lonely and isolated in parts and in fact there are times you question the value of what you're doing, especially because you don't see an immediate impact on the good you're trying to do. Once past a certain point I knew was halfway, every step was then a step closer to home and seeing my family again. I used to focus on small positives and hold just one positive thing about my day and fall asleep with it so I'd wake up positive and ready to go. I used to distract myself by counting to a thousand or saying hello to wildlife, touching gate posts and signs as I passed. I tried to always see the sun rise and set which gave me a great natural rhythm and feeling of connection.

In the remote highlands there are very few paths parallel to the coastline, so you're often clambering through thick bracken and heather, peat bogs, rock faces etc. It's great fun but it's hard work, and lonely

Physically, how did your body stand up to so many big days, back to back?

It's amazing how quickly the body adapts and gets into its own way of coping. After the third week I didn't get a single blister all the way home. I had minor injuries here and there but nothing serious, I got trench foot in Scotland but it was resolved fairly easily. My legs had good strength before, but now they have strength and endurance which is totally different. But it's also largely mental and becomes less about the physical.

How many hours would you tend to walk in a day, and were you forced to adapt your pace at all to factor in a bit of rest now and again?

My aim was to walk a marathon a day no matter how long that took. Some days people carried my bag on ahead and I was able to run so I'd complete the task quicker and get a longer rest period. I the summer I had nearly 18 hours of daylight so I'd just keep walking, often breaking 30/40 miles and the. I'd have short recovery periods but I'd just tell myself it would average out eventually.

Is it hard in places to stick to the actual coast? Were you forced to make many inland diversions around obstacles such as estuaries, firing ranges, fenced fields, private property, or industrial sites?

It is hard but it is doable. I stopped seeing estuaries as diversions, and they simply became part of the journey; firing ranges I was generally ok and made sure I checked the flags and firing times; fenced fields weren't really an issue except out in Ardnamurchan [where there's currently an intransigent landowner, Ed.] but there was a gate a mile or so inland. Most industrial sites have footpaths around them except some commercial docks. Private property is only ever a problem in Suffolk actually; often there'd be signs put up on a public path saying 'no entry' but if the path was on the map I'd use and not worry. So I was able to pretty much stick to the coast itself for the most part.

Large stretches of the coastline now have a dedicated coastal path – the whole of Wales and SW England for instance, and progress is being made on the rest of England. By contrast a lot of the NW highlands coast in particular is very rough, remote, fiddly terrain, where tracks and paths may not conveniently mirror the actual coast. How easy did you find it to make good progress up there?

I wild camped most of the time, but it was nice to be offered a bed occasionally so I could have a proper shower rather than wash in a waterfall or cold stream

The great thing about the highlands is how remote most of it is. The right to roam makes some aspects of the journey relatively easy, as no one challenges you, but being so isolated is hard mentally and physically. There are very few paths parallel to the coastline, so you're often clambering through thick bracken and heather, peat bogs with dead sheep in, rock faces etc. It's great fun but it's hard work, lonely and often difficult to resupply food but the water in burns and lochs is so clean you're fine to drink it mostly. By that point I'd been walking quite a long time and so I was into a good routine and I think that helped me personally. I know a lot of people struggle to get round certain areas like Knoydart and Cape Wrath, but it is doable - you just have to be a bit determined and sensible. They're not to be taken lightly though.

Was there much walking along beaches or the tideline?

Yes at every opportunity, in fact I regularly raced the tide to get round a rock line or to the next bay. I never really got completely cut off but I definitely got wet and had some hairy moments. The great thing about walking the beach itself is you can go barefoot and cool your feet!

It was a stormy winter – how did the weather treat you, and were there any particularly gruelling days?

Storm Arwen was pretty rough. I had been joined by my brother and brother in law and we'd walked from Dunnet to Dunnet Dead and then on to John o Groats; this in 90mph wind, sideways rain, trees and bins flying through the air. My brother nearly fell over a bridge wall into a weir and I had to grab him and pull him into the road. We were soaked through and pretty cold but managed to flag down a bus whose doors had blown off! We made the decision to go back to Thurso and book a room for the night to get dry and wait out the storm. The following day was bright and clear until about 3pm when the snow came again, and we had snow all down one side of our bodies but we still managed a good 20 miles.

How much of the time was spent alone? Are you comfortable in your own company, or did it ever get a bit lonely?

I think everyone gets lonely and I certainly do. But I've always been quite comfortable alone, most of my life has been spent alone travelling or doing things on my own, and you learn to love it. I had a few occasions where people came to join me for a day or two but generally I was alone the whole time and to be honest that's OK and just part of the challenge.

Saying that though, my mother came out to Edinburgh and ended up getting almost over the border back to England with me, my sister came out to Inverness and walked the Moray coast which was awesome, and of course my brother and brother in law came to the most northern point, which was cool.

As a father of three, how hard was it to be separated from your daughters for so long? How did you manage their experience of that, and did you manage to keep in regular contact with the family?

Really tough; it was the hardest thing actually. I recorded a bunch videos of me reading stories so they had them to watch when I couldn't get in touch but I only struggled for connection a handful of times in very remote areas. I also regularly did online talks with their school so they could see me and where I was. My wife brought them out a few times to see me during school holidays too.

You have had some healthy media coverage, and really good regular updates on social media: did the interest your journey seemed to generate help to keep you motivated and inspired?

I tried to always see the sun rise and set, which gave me a great natural rhythm and feeling of connection

Defintiely! I'm not great at social media but I was sending press releases to newspapers and radio stations regularly. I think in the beginning most people thought I wouldn't do it and then it got a bit of momentum the further I went and suddenly headed down from John o Groats again the end became visible and people really wanted to see me finish. It just snowballed.

Britain's coastline is both incredibly long and hugely varied. What, for you, is the most beautiful stretch of coast on the British Mainland?

I loved the part through Snowdonia and the Lleyn Peninsula in Wales, then all of the highlands. It will be pretty difficult to forget any of that.

I remember thinking that the west coast of the Kintyre peninsula was unreal, like a different planet; the heather was bright pink at the time and the beaches soft white powder sand at Machrihanish, with Caribbean clear blue-green waters. I loved it. The sky was on fire over Jura as well.

Can you give us a rough kit list, and the average pack weight?

Everything I took had to have more than one use, that's my golden rule. I go quite minimal and basic: one set of baselayers, one mid layer, one insulated jacket and waterproof jacket, bobble hat, one t-shirt, two pairs of socks; down sleeping bag and bivvy bag, linen scarf, two buffs, gloves, headtorch, battery pack and solar panel, Jetboil, GPS, multi tool and Swiss Army knife, book (luxury item) water filter, flip flops. That's pretty much it apart from a few days food rations.

What did you wear on your feet, and how many pairs did you get through?

Vivobarefoot Trekker FG boots originally, then the newer trail boot called the Forest ESC. I was given three pairs and rotated them every few thousand miles, they're all still good enough to wear.

What mapping/app did you use?

A combination of OS maps app and my GPS along with basic nav skills, I always like to have three levels of safety with stuff like that.

Where did you tend to spend the night – was there much wild camping?

Yes I wild camped about 80% of the time, and then was offered accommodation the other nights. It was nice to get an offer so I could have a proper shower rather than wash in a waterfall or cold stream.

Assuming there's a limit to how much food you'd want to carry on any given stage, how did you manage staying well fed along the way?

It became fairly opportunistic and I'd eat when or where I could but I often restricted my calorie intake and found I needed a lot less than most people think. I would carry 3-5 days worth of food in most places then in built-up areas carry less as it was easier to get food along the way.

Up in highland Scotland it's not usually hard to find clean drinking water as you go, but much of the rest of Britain's coast is more agricultural, or even built up. Was drinking water ever an issue?

Yes it was tricky everywhere but Scotland actually, some stretches of Essex it was so hot and limited on water sources. Often I was told I had to buy water instead of getting my bottle filled up so I'd then wait until I found somewhere else.

What about keeping clean – were there many cold dips in streams/the sea?

I love swimming in the sea so any opportunity to I did, but it doesn't really get you clean as salt just dries on your skin and creates quite uncomfortable friction in certain areas. So streams, lochs & waterfalls were my friends for washing unless someone offered me a room where I could shower or wash in a sink.

You're no stranger to long and arduous journeys. Can you tell us about a few of the others you've done prior to the coast walk, ones you feel were most significant or formative maybe?

I have essentially lived out of my backpack or a bag all of my life! I left my hometown after my A-level exams, having previously failed all of my GCSEs. I finished my exams early and bought a backpack and a ticket to Bangkok where I decided to walk the whole west coast of Thailand and its islands, eventually making it to Malaysia. I didn't have a phone or smartphone back then and Internet cafes were still relatively new. After six months I used a phone card to call home and I was told I'd got into university and had to come home. I flew back and moved into halls the following day.

While at uni I worked on building sites and in a computer lab at night to save money so I could travel at every opportunity. I cycled across Europe after my first year, from Cambridge to Greece. With just a small backpack and a bottle for water, I relied on the kindness of strangers who often didn't speak English, and I loved it.

I then walked across the north of India and the foothills of the Himalayas. Spent months in Russia sleeping in freezing conditions and even inside my backpack. I rowed across the Atlantic in a 105 day journey fraught with things that went wrong. I cycled three stages of the Tour de France back to back, and ran countless marathons and half marathons.

What attracts you to such tests of endurance?

I think it's about a mind-body connection. Having never been academic at heart despite eventually getting a degree in philosophy, I really wanted to understand myself and my place in the world. I don't know you can be taught that in a classroom or from a book or Google search. I think you can only learn that on the edge of your limits in testing situations. It's where you find fulfillment, and once you've achieved that you can start to truly give.

How did you get into it all?

I was born just outside London and moved around a lot as a kid then lived in Gillingham, Kent (the Medway towns are very built up and quite rough). I think the biggest influence was that I would spend my summers with my grandparents down in Somerset which is the most beautiful countryside and a place I still love. That certainly sparked my love of the outdoors, my Grandad teaching me about trees, weather, and all sorts of foraging along with practical things too.

Not content to walk 11,000 miles around Britain, you're now intending to join a team rowing around it later this year. Can you tell us a bit about that plan?

I am the skipper/captain of the challenger boat in this year's GB Row Challenge, the toughest rowing race in the world. We set off from Tower Bridge, London on 12/6/22 and we'll be collecting scientific data on the way round in a world first for micro plastics and marine EDNA too. Should take approximately 30-40 days. Six of us living on board a small boat and continuously rowing [not rowing, hopefully - Ed.] until we get back to Tower Bridge.

There's a strong environmental component to the journey too: could you explain a bit about that?

It's amazing. We're working with Portsmouth University's marine conservation department and are partnered with nature metrics to do all sorts of amazing things to help us understand migration patterns, pollution levels, temperatures, salinity levels, and sound mapping of the coast which has never been done before. It's hoped that it will inform our behaviours and help us understand how we can better protect our seas.

How are you preparing?

Row, eat, sleep, repeat! That's basically the gist of it. There's also a lot to consider, such as meteorology, navigation, tides times, crew personalities and capabilities, sponsors, safety equipment, and fit to leave certificates. Essentially though the important part is to row as much as possible to be prepared physically and then spend as much time together as we can as a crew in order to mentally prepare.

To read more about Chris, and the round Britain challenges on foot and by boat, see:

All photography copyright Chris Howard

- INTERVIEW: Exmoor Coast Traverse - England's Best Kept Mountaineering Secret 10 Apr

- REVIEW: Rab Muon 50L Pack 9 Apr

- REVIEW: Boreal Saurus 2.0 22 Mar

- REVIEW: The Cairngorms & North-East Scotland 1 Mar

- REVIEW: Mountain Equipment Switch Pro Hooded Jacket and Switch Trousers 19 Feb

- Classic Winter - East Ridge of Beinn a' Chaorainn 12 Feb

- REVIEW: Salewa Ortles Ascent Mid GTX Boots 18 Jan

- REVIEW: Patagonia Super Free Alpine Jacket 7 Jan

- REVIEW: Deuter Fox - A Proper Trekking Pack For Kids 27 Dec, 2023

- My Favourite Map: Lochs, Rocks, and a Bad Bog 27 Nov, 2023

Comments