Preparing for a big hill running round is a long hard road for anyone, but nearly dying doesn't usually feature in the training schedule. Rob Greenwood reflects on the cavernous lows and surprising highs of a truly life-changing year.

January is is far from my favourite month, with its short, dark days and cold, wet weather. However, being the start of the new year it does bring with it a sense of opportunity: plans to be made, things to look forward to. It was 2020, prior to all the weirdness that was to unfold - both personally and globally - and I had set my sights on doing the Bob Graham Round. I didn't just want to do it though, I wanted to do it well - do it properly. This meant, at least for the time being, becoming a runner again - something I hadn't been for a long, long time...

Standing in front of the Moot Hall is a surreal experience. Nowhere is it more apparent than here that you're about to embark on something very strange

I trained and trained and trained like a man possessed. I was focussed, driven and meticulous in my preparation, putting in the miles required to get a good time. I even started to work with a coach to maximise the gains and make my activity more efficient. I'd get up early throughout the week whilst the family were still asleep to get a run in before work, then at weekends I'd get at least one long run in. None of it felt like a hassle, because it was all part of the plan: to do the Bob Graham.

A spanner in the works

Things changed for me on 3rd February, when I started to throw up. It was debilitating, but nothing out of the ordinary - must be food poisoning… Three days later and I was still throwing up, only now I had diarrhoea too, so I called the local GP who suggested I had contracted a norovirus. As a result of its highly contagious nature they didn't want to see me at the surgery, so I went into a self imposed quarantine at home, unable to get out of bed, and watching all three seasons of The Crown in the space of three days (an achievement I'm still proud of, especially given my complete lack of interest in the monarchy).

Waking up in a hospital bed, unsure how you got there, is a strange experience. Stranger still is asking someone where the toilet is, only to be told that there's a tube coming out of your penis and you can pee anytime you like

Five days in and the vomiting stopped, not least because I hadn't been able to eat anything, but in its place came severe stomach pains, so I called the GP again. This time they suggested it was gastroenteritis, and to combat the pain they prescribed codeine. This made a difference for a day, but only a day, and 24hrs later I was in an immense, all-consuming agony that I find hard to put into context. Everyone's pain threshold is different, and I'd like to think mine is quite high, but doesn't everyone say that?! Either way, this felt bad - very bad.

My memory of the events that followed is hazy, partly because of the pain, but also because of the fact it's hard to truly remember now that I'm so far removed from it, and the events themselves feel like a dream - or something that happened to someone else. Even at the point the pain was clearly uncontrollable, I still wasn't sure if I was being a hypochondriac. Thankfully Penny, my wife, was more level-headed, and what she was witnessing was clearly not normal. An ambulance was called, but was going to take too long, so she took me to the hospital, leaving our young daughter in the care of our neighbours. On arrival at Northern General in Sheffield I lay down on a stretcher, curled up in foetal position, vaguely aware of people moving around me, but not really caring what they were doing or saying. I remember being given morphine for the first time (ever) and being blown away by its potency. For the first time in a week the pain, so present and powerful, passed through me as if it were all imagined, and finally I could rest.

There's a fine line between waking up and coming to when you're on morphine, but I woke up the following morning to a team of doctors informing me that they were going to operate, remove my appendix, and that this was 'the plan'; however, due to the nature of these sorts of things, 'the plan' might change once they went in - depending on what they found. I went into the operating theatre without even the slightest bit of trepidation, not least because I trusted the medical staff fully, but also because when you feel so utterly out of it, and when you're in that much pain already, you really don't give a shit - you just want it to be over. This was the first time I had ever had a general anaesthetic too, but much like the morphine I was grateful for the time out.

As events transpired, things didn't go to plan. It wasn't just a simple in/out operation, as my appendix had long since ruptured, leaving in its wake a severe case of sepsis and peritonitis. Whilst I'd heard of sepsis, I hadn't heard of peritonitis (or how serious it was), and it was that which came close to killing me. Waking up lying on a hospital bed, unsure as to how you got there, is a strange experience. Stranger still is asking someone where the toilet is, only to be told that there's a tube coming out of your penis and that you can pee anytime you like. The fact I hadn't even noticed this says a lot about my physical state and the fact I saw this as a positive says a lot about my psychological state, although given the size and width of the tube I was pretty grateful that I didn't remember exactly how they got it up there…

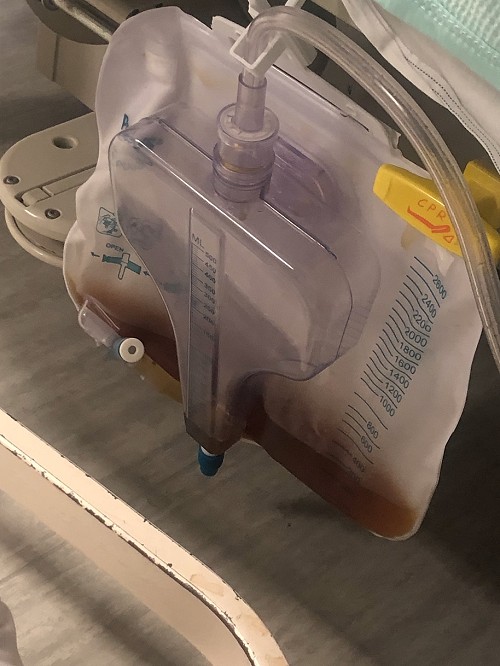

There were further tubes sticking out of me: one from the left hand side of my abdomen, which was draining blood and pus into a bag, then a canular coming out my arm, which was feeding my body what felt like an endless course of antibiotics and other fluids. Down the centre of my abdomen was a long dressing which I was desperately trying not to think too much about. Every climber knows the importance of the abdominal muscles and mine were now cut in two.

Surviving that night was one of the hardest experiences of my life

I've forgotten if it was one or two days after the operation, but I was lying in bed trying not to move when one of the nurses came over and said that I had to try and sit in the chair beside me. Such an easy task, yet the prospect of doing so in my current state was akin to being asked to onsight an E7. I felt in danger just by thinking about it and didn't have a clue how to actually go about achieving it, because I really couldn't move. It required the help of two nurses, who offered advice on the technique required to roll out of bed, but still - the pain was almost overwhelming and when I did finally get sat up in the chair my insides felt heavy, like they were going to fall out. My lungs felt tired from the general anaesthetic too, and I spent most of the day asleep, in and out of consciousness, oblivious to the comings and goings of hospital life, only waking to request more medication.

As the days went by I made an effort to sit up in my seat, then - as time went by - attempt to walk. The slow shuffle was made even slower by the fact I had various bags to hold in addition to all the tubes coming out of me, and - as if that weren't enough - a stand containing whatever IV I was hooked up to at that point in time. It's hard willing yourself to do something that really hurts, even if you know it's doing you good, and the pain never really passed. However, after twelve days I was discharged.

When you're let out of hospital the one thing everyone says is that you'll feel better at home, which is very much what I'd hoped for, but not what I got, as I only lasted 24hrs before being rushed back into hospital again. Arriving late at night, it took a while to be seen, and during this time I had no pain relief. I underwent something known as tremors, which is one of the most frightening experiences I've ever been through, and my body started to shake to the point of convulsion. I was lucid throughout, but the pain went beyond anything I'd experienced so far, with nothing to take the edge off. I genuinely thought that this could be the moment I'd die, shaking uncontrollably, sweating, whilst screaming for help, when none could be found.

Surviving that night was one of the hardest experiences of my life and in the morning when I came to, I was once again surrounded by doctors, telling me 'the plan'. I was to be operated on again, this time to remove a section of my intestines which had become twisted. I remember the surgeon being kind and that kindness felt like something special given the experience of the night before.

The following day I awoke in a familiar position, laying on a hospital bed, with a pipe once again up my penis. My scar, which had been healing nicely, was now something new - something different - and a lot longer. Hidden beneath the dressing I could feel staples holding me together. The very thought turned my empty stomach. I went through the same battles to sit on the chair, then the same again to get back standing. It was Groundhog Day in a never-ending cycle of shitness that kept going round and round and round.

To save any repetition I'll dive straight in with the spoiler: I got better.

On 27th February I was discharged for the last time and free to go home. This time it was as they promised - lying in my own bed felt so good. Seeing my daughter again was indescribable, although it was bittersweet, because I didn't have the power to play with her. All I could do was lie in bed, rest, recover and eat (in total I lost 13kg, so there was a lot of weight to put back on). Ordinarily these are things I am terrible at, but given how totally and utterly toasted I was there was no other choice, because I wasn't actually capable of anything other than this. And my hefty napping schedule meant there weren't that many hours in the day when I was awake.

Aside from the fatigue, the other thing I had to contend with was the scar. After the first operation it was tied together neatly with strips of stitches, but the second had required something more industrial, bringing with it big, beefy staples. After a week of being out of hospital these had to be removed, which presented the next hurdle. I've forgotten the doctor's exact wording, but it was something to the effect of "you'd be extremely unlucky to have the entire wound open up again", but after a series of monumentally unlucky events its likelihood seemed almost guaranteed, so bit by bit, as they removed each of the staples, I opened up more, and more, and more, to the point which the only thing holding me together was my belly button.

Over the next few months I had daily trips to the wound clinic to change my dressing. Throughout this time I was on/off antibiotics, as infection kept wreaking havoc, brought about by the stitches that were still sticking out of me. Wound aside I was showing signs of improvement: I went from two naps a day to one, then one nap a day to none. I also managed to get back up and out of bed again, attempting short walks. At first these were just in the house and up the stairs, after which I'd need to lie down, sleep and recover. Bit by bit I worked my way up to going into the garden, then down the road, then a little further.

Around this time COVID had well and truly hit our shores and as of 16th March we went into our first national lockdown. Since I was already in a state of self imposed lockdown it made little or no difference. It was during this time that I made my first steps outside, into the hills surrounding my home. My initial forays up to Bamford Edge, just above where we live, saw me reach the field just before and sit down, content with my achievement. Whilst I may not have made the summit that day, it felt like a breakthrough, and it felt good to be lying down amongst the bilberry bushes in the warmth of the sun - a far cry from the artificial light and ventilation systems of the hospital ward. I was alive…

Unexpectedly it was climbing, not running, that drew my attention, once I was able to. The Bob Graham was far from my mind for some reason, probably because of how unrealistic a prospect it was, and the desire to climb really was burning. However, the big question was what I could climb, given my physical state. So I started from the bottom and worked my way up. Given the restrictions we couldn't go far, but I wanted a crag I could throw my heart and soul into, and - of all the crags in the world - I chose Stoney Middleton. I remember when I did my first lap of Minus Ten, then how that one lap became two, then two became four, then four became forty minutes of back and forth - albeit over quite an extended time frame. I climbed routes I'd missed out on doing previously, as my focus had then been to climb the harder classics, whereas now I was looking for routes of a more reasonable grade.

I've often found that the more you invest yourself in something, the more you get out of it, so that's what I decided to do

Given my physical state I was convinced that I would be climbing somewhere between VDiff and VS all summer, or perhaps forever. This wasn't an unattractive prospect on either account after what I'd been through, as I just felt grateful to be alive, but I was surprised when I felt ready for more. I still had to be careful, as I do now, because my abdominal muscles still suffer from several centimetres of separation, but if I picked my route and made sure it was the right gradient (i.e. not too steep) then I was in. Whilst you may lose your strength, you don't lose your ability, and my movement was my greatest asset. Over the coming months I continued to surprise myself and by the end of the year, in spite of everything that happened, I had potentially had one of the best year's climbing of my life, with highlights (at least in terms of difficulty) including redpointing The Squealer (7c) at Lorry Park Quarry, headpointing Scarab (E6), flashing Losing Control (E5) in Pembroke, and completing In the Flick of Time (7C).

But the real lesson was in how much joy there is to be gained simply from climbing - irrespective of the standard. Final's Flue at Stoney Middleton stood out as a fine example of this, being absolutely ridiculous, yet hugely gratifying - not least because of the company.

Getting back on the trails

As winter came I continued to climb, but at some point around November I felt the desire to go running again. Climbing walls were closed, and even if they were open I had no interest in going, as I just wanted to be outside in the elements.

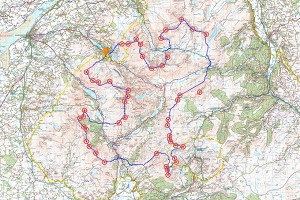

There was also the matter of that unresolved Bob Graham. The truth was inescapable: if I was to do it, I'd have to do some running. So that's what I did, but there was a difference to last time. Previously I was keen to get a good time, whereas this time - after everything that had happened - I just wanted to do it in my own time, in my own way. I still aimed for under 24hrs, but I decided to run it on my own, as this would give me time within my own head to reflect on the weird year I'd had. However, I didn't want it to be an entirely solitary affair, so drafted in my family to meet me at the roads, as their involvement in my recovery - and my round - was also very important to me.

My first fleeting runs here and there felt forced, which left me wondering why I was doing it. In those dark nights of deep winter, donning your head torch, thermals and waterproof before setting out into the apocalypse leaves you asking some pretty soul searching questions; however, the desire to do the Bob Graham, and to put the events of the last year to rest, meant I knew that that I needed to get it straight within my own head: I was either going to do it (and commit) or accept that for one reason and the next, it was not meant to be - at least not now.

I've often found that the more you invest yourself in something, the more you get out of it, so that's what I decided to do. Rather than go for the occasional run here and there, I would commit myself to getting out more frequently. Changing my approach had a transformative effect, as it went from feeling like a chore to being something I looked forward to. I enjoyed planning long routes, exploring paths and places I'd never been before - even though they were on my doorstep. Around this time we were also blessed with some distinctly wintery weather. To some, this could have been a hindrance, not least because it made everything quite un-runnable (not to mention absolutely freezing), but it also made for some incredible days out.

The only moment I faltered was when the weather got unseasonably good in February and my psyche wavered, mostly because climbing in the sun is - lest we forget - much more fun than going for long runs across what felt like the arctic tundra. A few weeks went by, the weather changed, and I was back on track again, but now that spring was (sort of) upon us there was just one minor issue to confirm - when was I going to do it?! It's one thing thinking about doing it, but another altogether to set an actual date and say that this is when you're going to do it.

In early April, in spite of all my preparation, I was still sitting on my hands regarding setting an actual date. Then a message came from a close friend - Calum Muskett - asking me if I wanted to pace him on his Paddy Buckley attempt. What ensued was typically Calum, who approached the big round much like he approaches a big route: with confidence and audacity. I joined him for the final two legs, which culminated in us reaching the top of Tryfan with 34 minutes to spare, then the A5 with 4 minutes to spare, then Ogwen Cottage - the finish - with exactly 10 seconds to spare. Witnessing what Calum went though was up there with one of the most inspiring things that I've ever seen. Whilst he stacked a whole host of odds against himself, namely setting off way too quickly, not reccying the route, and neglecting to apply suncream or wear a hat, he also rode through those colossal lows, kept going, and did it. In doing it he also made me realise that I could indeed do my Bob Graham. But in order to do it needed to set a date, so that's what I did - the following weekend…

Whilst I was aware that pacing someone for 10hrs probably wasn't the best form of tapering (in fact, it was the exact opposite of tapering), I had a weather window - and weather windows aren't something to ignore. This was it, or at least it was until I woke up on the Friday morning - the morning we were supposed to be driving up to the Lakes - vomiting again. I'm still not sure what it was, or how I'd got it, but either way I wasn't going to be running anywhere that weekend. I felt pretty mortified, especially after everything that had happened. Time was now really tight to get another attempt in, especially one with as good a weather window as the one I'd just missed. I felt cursed, but the day was only going to get weirder. Around midday, as I was lying in bed, Penny went off to get a blood test from the local GP surgery. Over the past years she's had a condition of her own to contend with (hyperparathyroidism -google it if you're interested) and the blood tests were a means of keeping an eye on her calcium levels; however, on this occasion she came back from the GP with some unexpected news - she was pregnant. Whilst this was excellent news on the one hand, as we'd been hoping to have a second child at some point in the future, it was alarming on the other, as we knew that Penny's condition would have a detrimental effect on both her and the baby.

Whilst doing the Bob Graham was undoubtedly a lifetime achievement, it pales into insignificance compared to how fulfilling having a family has been

Hyperemersis Gravidarum is a very severe form of morning sickness and it took hold of Penny pretty much immediately, rendering her bed bound and incapable of doing anything other than sleep (and be sick). I looked after her, took Tilly to nursery, then worked throughout the day. It never felt like a chore in spite of the effort required, because after the last 12 months my priorities were pretty clear - family comes first. That said, this doesn't stop you from feeling the desire to do other things and in spite of everything that was going on, the Bob Graham was still calling. If anything, there was an even greater sense of urgency, as it was apparent that things were only going to get worse as far as Penny's health was concerned, so it was now or never. By chance a slender weather window presented itself the following weekend and with Penny's all important blessing, it was, at long last, 'on'.

This is it - the Bob Graham is on!

Standing in front of the Moot Hall is a surreal experience. Nowhere is it more apparent that you're about to embark on something very strange, as you know that by the time you're going to be stood in this spot again the rest of the world will have had a good night's sleep, woken up, eaten breakfast, gone about their day, had lunch, eaten dinner and will probably be contemplating what to do before bed. In the meanwhile, you'll just have been running. There's a blissful simplicity to it, but the gravity of it weighs heavy on the mind.

If standing outside Moot Hall is surreal, the actual moment you start represents the next level of weirdness. All that pressure, all that tension, manifests itself into extremely slow, anticlimactic run (otherwise known as a walk) up Skiddaw. At this point I was lucky enough to tag along with a team of locals, who were pacing another Rob (a stronger, faster and more talented model). Whilst I hadn't anticipated any company, it was nice to have a social start. The night sky was clear, the temperature was cool and crisp, and the ground was - for the most part - dry (aside from the ever-present bog that presides upon Mungrisdale Common - does that thing ever dry out?!).

The pace was a bit quicker than I might have gone had I been on my own, but wasn't unreasonable, and before I knew it we were descending Hall's Ridge off Blencathra. I could see the bright lights of Threlkeld in the distance and the end of the first leg. I'd intentionally allocated a bit of extra time at each road crossing, partly because it was the only time I was going to see my parents (or anyone for that matter), but also because I didn't want to feel like there was any rush. Small luxuries like a cup of tea (or several), a change of shoes and socks, a moment to chat, say thanks, and see you later. These were things I knew I'd appreciate. In reality I almost always left a bit earlier than the allotted time, but that too was nice, because it put me at a psychological advantage, as I gained free time back on the schedule without having to run faster.

As a result of this relaxed approach I parted ways with the more professional Cumbrian team. As I began my own way up the road towards Clough Head it felt nice to be alone and able to settle into my own, slow pace. One of the nice things about running at night is it tends to bring with it a more relaxed pace. There's no need to rush (in fact, it's probably a benefit if you don't), so it's just a case of settling into your rhythm and not getting overexcited. As it was, I felt good - really good in fact. I was eating and drinking well, keeping plenty in reserve, and was happy with how things were going. Being on my own allowed me to take in the nighttime landscape, with the ridge ahead stretching before me. When the moon rose it took me completely by surprise (in spite of the fact that its presence shouldn't have come as too much of a shock). It was absolutely massive, hanging low over the eastern hills, and with a blood red colour. The ground was frosty and its glittering kept reflecting the light of my headtorch, creating a kaleidoscope of colour that made the ground look purple. Navigationally this leg is quite straightforward, so I just focussed on the running (and not f**king it up), and before long I found myself descending towards Dunmail Raise. Once again, I looked forward to seeing my parents, having some company, drinking tea, and getting stuck into the third leg.

The third leg is undoubtedly the crux of the round, not only being the longest, but also the most navigationally complex and technically hard. Part of the challenge is the macro nav (i.e. going the right way, towards the correct mountain), but the other is the micro nav - weaving your way between subtle variations that can save or lose you time here and there. When added up, these seconds amount to minutes and these minutes make hours. Given that I had never actually run this leg before I was conscious that I needed to be on top of my game not to lose too much time. Thankfully the weather was holding and the fell tops were free from cloud. The sun rose behind me, bathing me in a warm amber glow, which contrasted with the crystallised light reflected off the frost. This was the most magical moment on the entire round.

At this point I had been running for around 10 hours, which is - I think it's fair to say - a substantial amount of time; however, it is eclipsed by the 14 hours of running that I had ahead of me. At moments like this it's easy to freak out. Stake Pass, which is about where I was at this point, is a classic bail point as a result of this. In an effort not to let the magnitude of the task overwhelm me I focussed on whatever fell was coming next. Having to concentrate on navigation helped, as it meant I had something else to focus on, but running on your own means that there aren't many options to escape from your own mind - hence you've really got to try to stay happy, particularly if you want to have fun and enjoy the experience whilst it's actually happening. Great though type two (aka. retrospective fun) is, I was keen to have a good time in the moment.

Arriving on top of Scafell Pike at 9:30am was, like many other experiences on the round, surreal. On its summit you meet a lot of happy hill goers who have achieved their own lifetime aspirations by reaching the top of England's highest hill, whilst you're midway through your own challenge. There's a sense of a shared experience, as we're all up there for the same reasons, albeit with differing distances. Descending towards Mickeldore, away from the early morning masses, Broad Stand presents itself. This 'Mod' comes with a reputation, courtesy of its polished passageway, sloping ledges and monumentally awkward corner. As a climber its difficulty doesn't present too much of a concern, but does deserve respect, as a fall would almost undoubtedly be fatal. In addition to this, it's not actually that easy - especially when tired - and I moved cautiously as a result of this. The descent from Scafell to Wasdale is much like the descent from Blencathra to Threlkeld and Sandal Seat to Dunmail Raise, insofar as it's an absolute quad-busting beast that feels like it goes on forever. Perhaps counterintuitively, it's descents such as this - and not the big ascents - that tend to take the greatest toll.

Upon reaching the valley floor it was my Dad that met me, as my Mum had gone back to where we were staying to look after Tilly, as Penny was still bed bound. Whilst this weighed on my mind, there wasn't much I could do other than to finish what I'd begun doing and knock off the Bob Graham. This was not how I'd have planned it, but given everything that had gone on over the last 18 months it just felt like there was no point in planning - or having expectations of any kind. You just had to take the moments you can and make the most of them, because you never know when you're going to get another.

As with a long illness, during these rounds it's easy to forget that whilst you're knackered, so too are the people supporting you

The start of the fourth leg is marked by the unrelenting uphill struggle of Yewbarrow. It's steep, uncompromising, and a route that you would never ever take were you not to be doing the Bob Graham. The weather at this point was strange too. It was still bright, and really quite warm when you were in the sun, but there was a persistent, biting breeze that meant when the clouds came over it was really quite cold. After putting my windproof on, then taking it off several times I admitted to myself that there was no perfect solution, other than to stop wasting time removing and reapplying different layers. In terms of time, I was undoubtedly slowing, but not concerningly so. Throughout the first two legs I'd been at a 22:30 pace, but this had slipped to 23:00 on the third leg. Mid way into the fourth and I was conscious that this had become nearer 23:30, but I was still feeling good, so just needed to be careful not to waste any time. Ironically, that is exactly what I did, taking a few poor lines. None of these were major, but each represented a minute here and a minute there which would be hard to catch up on by running faster.

In spite of this, I reached Honister in good spirits. My Dad, however, was starting to show signs that the non-stop support-a-thon was taking its toll. As with a long illness, during these rounds it's easy to forget that whilst you're knackered, so too are the people supporting you. Dashing around the Lake District for 24 hours, not getting much sleep, is pretty exhausting - irrespective of whether you're running or driving. It was great to see him though, even if he was as incoherent as I was. Whilst I wouldn't say I was looking forward to the ascent up Dale Head (the world's largest small mountain), the prospect of setting out on the fifth and final leg was a huge boost, because I knew - all being well - that I'd done it. That said, the last leg, despite being short, isn't that short; it still involves three more hours of running, so you've got to settle in and either enjoy or endure the ride over Hindscarth and Robinson, then the rolling ridge-line down into Newlands. The road that follows is probably one of the least pleasurable bits on the Bob, as it goes on forever, and despite feeling like it should be flat it's remarkably undulating (and by this stage, undulation of any kind is the last thing you need).

After what felt like a long, long time I arrived into a bustling high street filled with people. Usually people opt for a crowd pleasing sprint to the finish, only I had nothing to sprint for. I wasn't in it for a time, and there was no point pretending, plus I was genuinely relishing each and every moment, because I - at long last - had made it. People were clapping, including my Dad, and I stood there in a state of disbelief. I'd done it. I'd actually done it. 23 hours 38 minutes. After everything that had happened, I'd finally done it.

Postscript

On our return home from the Lake District it became apparent that whatever was wrong with Penny wasn't getting better. It was, in fact, getting worse. We booked a doctors appointment, got a blood test, and as soon as the results came back she was admitted to hospital, which is where she stayed for the next six weeks. It was my turn to look after Tilly, reversing the roles from back when I was ill. We celebrated both Penny and Tilly's birthdays in the carpark at Northern General. Bleak though that might sound, it reaffirmed something that had been so clear to me throughout my own hospital stay, which is the family (and friends) mean everything.

On that note, many thanks to my own family, and Penny's, for all the help throughout a weird year. Thanks also to all the friends (you know who you are) for your support. Thanks too to Alan at UKC for being such an understanding employer, providing time off whilst I was sick, then being similarly sympathetic whilst Penny was ill. Another special mention goes out all the medical staff who looked after me, but in particular my second surgeon, consultant and the incredible team of nurses at the wound clinic at Newholme Surgery in Bakewell.

Finally, the greatest thanks go to Penny - I couldn't have done any of this without your love, encouragement and understanding. Whilst doing the Bob Graham was undoubtedly a lifetime achievement, it pales into insignificance compared to how fulfilling having a family with you has been.

- PHOTOGRAPHY: UKC/UKH Photography Awards 2023 - Winners 15 Mar

- PHOTOGRAPHY: The North Face & Ellis Brigham Photography Awards 2023 - Category Finalists 16 Feb

- GROUP TEST: Performance Headtorches - Petzl Nao RL, Silva FREE and Black Diamond Distance 1500 2 Feb

- REVIEW: The North Face FUTUREFLEECE Hooded Jacket 24 Jan

- REVIEW: Montane Phase Nano - The Ultimate Running Shell? 17 Nov, 2023

- REVIEW: Patagonia Triolet Jacket - PFC-Free, and Built to Take Abuse 3 Nov, 2023

- Sustainable Gear: The Evolution of Gore Tex - ePTFE, ePE and PFC-free DWR Treatments 1 Nov, 2023

- ARTICLE: The Big Three Rounds - All You Need to Know: Part 2. Reccying 28 Aug, 2023

- REVIEW: One Man's Legacy, by Mike Dixon 22 Aug, 2023

- REVIEW: Boreal Flyers Mid 11 Aug, 2023

Comments

Truly inspiring Rob. A great account which is both moving and entertaining.

What a story - despite all your tribulations, still a minute quicker than me and I had no excuses!

Thanks a lot, it makes me feel a bit less bad about the sciatica which is currently keeping me off the hills, at least I don't have the horrible disfigurement (or the scars 🙂)...

Bloody hell, Rob! What a story - heartwarming, inspiring and scary all at once.

Thanks for sharing Rob. Fascinating, Horrifying, Inspirational and Heartwarming all in one piece. An epic story of accomplishment. :)

Brilliant, Rob! Thanks for this - inspirational and a definite wake-up call for those of us who struggle to get off our arses at the best of times!

Cheers, Andy