It was in December of 1933 that Patrick (Paddy) Leigh Fermor took a taxi to Tower Bridge, trotted down the rainswept steps of the Thames to a small Dutch freighter, and set off for Constantinople. On foot, of course; on a budget of £1 a week – which was quite a lot of cash in 1933. His route-plan was simple. Up the Rhine, and then down the Danube.

Before World War II, it was still possible to stride out, towards somewhere a few thousand miles away, using the public roads as Robert Louis Stevenson and Modestine the donkey had done a hundred years before. In the same way a couple of years later, Laurie Lee was heading south across Spain – and even the randy and arrogant young Alfred Wainwright, hitting northern England on his way to Hadrian's Wall.

Leigh Fermor was 18 years old, already kicked out of several schools, hanging around London waiting (though he didn't know it) for the start of World War II. The moment of decision – I'm always interested in those ten-second events, where someone decides to spend months, in Leigh Fermor's case 13 of them, in pointless walking (or rowing in a boat, or building Chartres cathedral out of bits of string). Leigh Fermor is the first to give – not a rational explanation – but at least an explanation. "A new life! Freedom! Something to write about!"

And write he does. Weaving words into townscapes, and skyscapes, and whole kingdoms of dream. While he's blind drunk from mixing beer with schnapps, and in a German police cell, a pimply youth at the youth hostel walks away with Fermor's rucksack. Along with his first two hundred miles of 'the flowery descriptions, the pensées, the philosophic flights, the sketches and verses…' Fermor just had to write it all up again, from memory. And perhaps a whole lot better the second time around? We recall the masterpiece of WH Murray, a few years later - confiscated by the Gestapo and done all over again on a whole fresh lot of toilet paper:

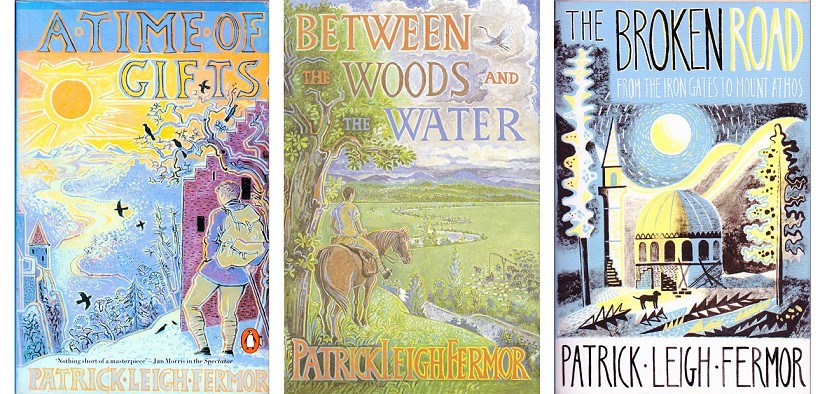

'A Time of Gifts' is considered as one of the very great works of travel writing in English. "Nothing short of a masterpiece" says Jan Morris (a great travel writer herself, who died in November, and in an earlier life as James was reporter on the 1953 Everest ascent). And when it comes to distance walking, Tower Bridge to the Iron Gates of the Danube certainly counts as long. So how come this one didn't make it onto my list of Literature Classics a whole lot earlier than No. 19 in the series?

It could be because, as literature, it's just a bit too literary.

A walk is a story, whether or not you file it on the shelf called Non-Fiction

Words like 'gasoliers', 'congeries' and 'noctambulism' are spotted like dog turds across the path of the inattentive reader. Paragraphs take a whole page long. And that whole page could be a detailed account of various nasty martyrdoms in the paintings of Albrecht Altdorfer (1480–1538). Meanwhile quotes can be in German or Latin – lucky us ignorant moderners have access to Google Translate, eh? Well the bad news is that Google Translate is a whole lot worse than General Kreipe at deciphering Latin verse. (Hint: the words may be rearranged in any order to fit the line.)

The walking is long – and so is the writing. 'A Time of Gifts' is just the first volume, taking Paddy as far as a random bridge over the Danube on the way into Hungary. Volume 2, 'Between the Woods and the Water', carries him on to the Danube's Iron Gates gorge, a bit short of Bulgaria. It was only after his death, a full 80 years after the original journey, that the final volume 'The Broken Road' finally carried him to Constantinople.

Some of it Is heavy going – not just the knee-deep snow through the forests of the Rhineland, but also for the severely taxed reader. "The vigorous Teutonic interpretation of the Renaissance burst out in the corbels and the mullions of jutting windows and proliferated round thresholds. At the end of each high civic building a zigzag isosceles rose and dormers and flat gables lifted their gills along enormous roofs that looked as if they were tiled with the scales of pangolins." But then comes the wondrous two-page setpiece of the Munich Beerhall, the great cylindrical mugs banging like a battlefield, the stout burghers shooting themselves in the face, as it were, with the wide pewter cannon and falling backwards to be carried away by the stretcher-bearers.

And given that it's all a rewrite, there seems little point in the accusation that Leigh Fermor simply made a lot of it up… A walk is a story, whether or not you file it on the shelf called Non-Fiction. And the two minor princesses in Stuttgart, who pick up the scruffy wanderer and take him back to their parents' palace – maybe they do seem impossibly romantic. But then again, so does the episode with General Kreipe.

General Kreipe? A year and a bit across Europe left Leigh Fermor superbly qualified for a certain form of warfare. And an interrupted but posh education, with its term or two of ancient Greek, determined where that warfare would be. Parachuted into occupied Crete, Leigh Fermor led British agents and Cretan shepherds in kidnapping General Kreipe, the commanding officer of the island. In a cave high on Mount Ida (aka Psiloritis), Leigh Fermor and his captive exchanged snatches of verse. In, of course, the original Latin.

Which is how a long distance walker and writer got played, in the movie, by Dirk Bogarde.

Epigraph (from Petronius) as randomly translated by Google

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan

- My Favourite Map: Geology Plus Glaciers 11 Dec, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mini Guide: The Cheviots 27 Feb, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

Comments