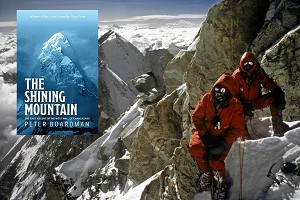

There are books you can come back to many years later, and find whole new levels of meaning and significance. Those books tend to be the classic novels, or perhaps the plays of Shakespeare. Not books about climbing. But is this an exception?

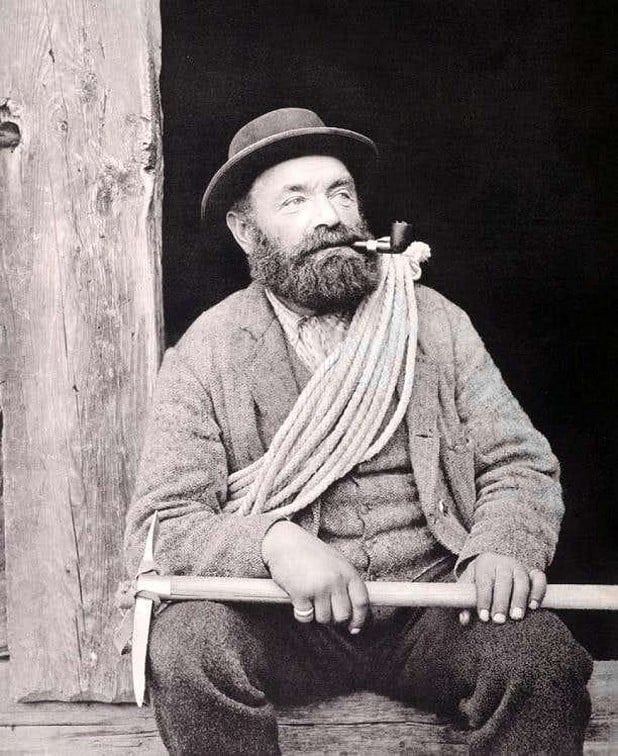

On first reading, 'My Climbs' by Albert Mummery is an exciting account of early Alpine ascents. And in that genre it's possibly supreme (I write 'possibly' as I haven't yet read Leslie Stephen, the early mountaineer who was also Virginia Woolf's Dad). By the 1880s, the easy and obvious mountains had been climbed and the Hörnli ridge on the Matterhorn had become a trade route. In partnership with friends such as Cecil Slingsby (him of the chimney on Scafell) and Norman Collie (he of Collie's Ledge on Skye); but more particularly the guide Alexander Burgener, Mummery was seeking out "the most difficult routes on the most difficult mountains". And he wrote about them in a vivid and fun-loving style, laced with Victorian wit.

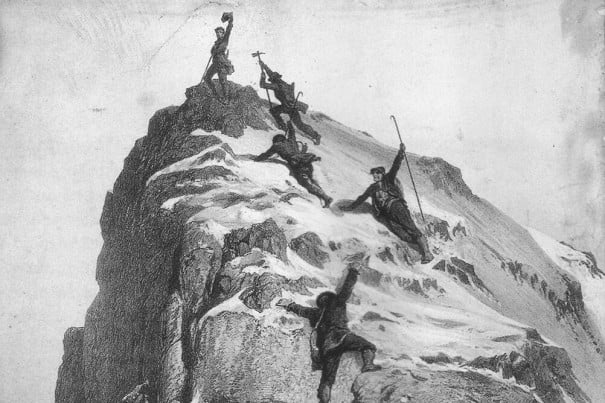

Their climbing was at a level of danger found today on Alpine-style climbs in the greater ranges. Exploring took them up the classic routes – the first ascents of both the Zmutt and the Furggen ridges on the Matterhorn, the Aiguilles de Charmoz and Grépon. But you don't find the Furggen without also explorations of less satisfactory ground. The Col du Lion, at the foot of the Matterhorn's Italian ridge, was undertaken because "no more difficult, circuitous, and inconvenient method of getting from Zermatt to Breuil could possibly be devised than by using this same col as a pass". The ascent was on loose rock, black ice and unstable snow. Crampons, remember, have yet to be invented. This is all to be done with step-cutting, with the rope for reasons of solidarity. If the leader should slip, the second man would be following him down into the bergschrund. But the really stimulating aspect was the stonefall. By half way up the gully, and the sun shining, the lower part was being bombarded from the slopes of the Matterhorn, greatly motivating the completion of the climb.

Taken on its own level – that level being around the 4000m contour – this is a classic of Alpine writing, especially if you fancy some of these climbs in today's much easier conditions of guidebooks, proper protection, and ropes that don't break. And perhaps it's just me, on re-reading, to find also a fascinating character study. Fascinating because unresolved. Mummery a Victorian English gentleman, member of the exclusive Alpine Club, complete with sense of entitlement, the appropriate class prejudices, and a public-school sense of humour. And Alexander Burgener, speaker of Schweizerdeutsch, son of a peasant farmstead somewhere below Saas-Fee. Burgener very sensibly insisted on some training climbs first to find out if this fellow could climb. But within five days they were sharing the first ascent of the Zmutt.

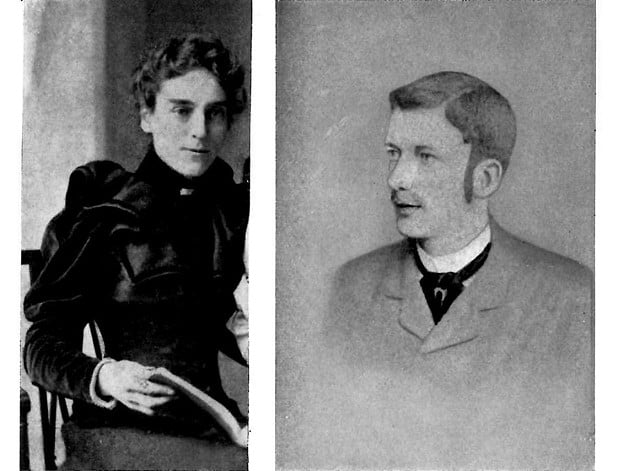

And then there's Mrs Mummery – her first name was Mary, though this isn't revealed in the book – along with her friend Lily Bristow. Burgener invited Mary Mummery along on the first ascent of the Teufelsgrat on Switzerland's second highest mountain, the Täschhorn, and she gets to write the relevant chapter. It's a ridgeline like a Disney cartoon, a few centimetres wide with vertical sides dropping 600m on either side. Today it's graded D for Difficile, with rock pitches graded V, and reckoned to take 8 hours for modern climbers with modern gear starting from a bivvy at 3638m. Burgener and the Mummerys started from Randa at the valley floor (1409m) at 1.30am after a night practising Strictly Come Dancing a century and a half too soon.

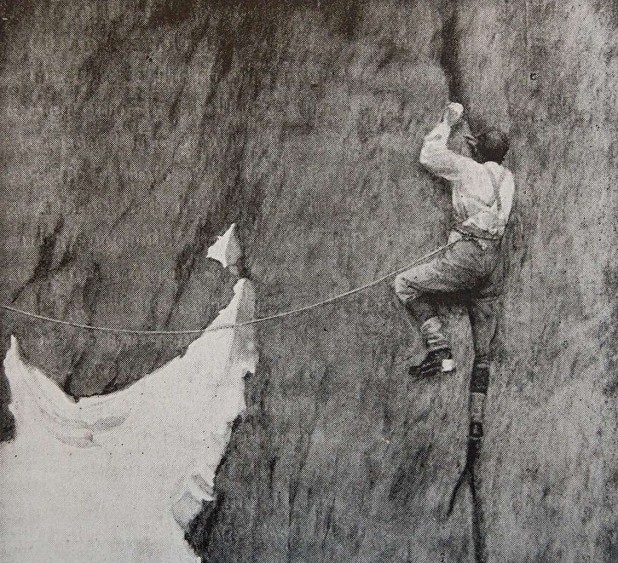

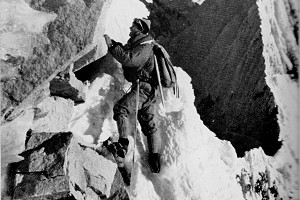

Meanwhile Miss Lily Bristow scandalised respectable climbers by sharing a mountain tent with Mummery and his friend Hastings as a high camp before an early re-ascent of the Grépon. She took the photo of Mummery in the so-called 'Mummery Crack', using a massive half-plate camera, then "showed the representatives of the Alpine Club" – which of course did not admit women – "the way in which steep rocks should be climbed". And that's about it for Lily. She wrote an article about the Dru accepted by the Alpine Journal. And she may be the model for Lily Briscoe in Virginia Woolf's 'To the Lighthouse'. According to Litcharts.com, "observant, philosophical, and independent, Lily is a painter pitied by Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay for her homeliness and unattractiveness to men."

In 1895, Mummery was about 50 years ahead of his time by becoming the first mountaineer to die on an 8000m peak – caught in an avalanche while attempting the Rakhiot Face of Nanga Parbat. Herman Buhl, who made Nanga Parbat's first ascent nearly 60 years later, described Mummery as one of the greatest mountaineers of all time. Mummery's book – plus Mary's contribution – is the defining account of what's called the Silver Age of Alpine Mountaineering. With just one niggling doubt – I do still need to read that Leslie Stephen.

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan

- My Favourite Map: Geology Plus Glaciers 11 Dec, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mini Guide: The Cheviots 27 Feb, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

Comments

It is good to be reminded of this mega-classic of Alpine literature.

Two quibbles. One, I think you are a bit harsh in omitting any mention of Whymper's great classic 'Scrambles Amongst the Alps' - arguably the greatest piece of all mountain literature. Two, I'm rather surprised you don't tell us more about the Mummery Crack, which I've been told by those who've done it is possibly as hard as 5B, and so would have been E1 done with no protection, as Mummery did it in 1887, or whenever it was.

Actually, a third quibble too. The omission of Stephen's 'Playground of Europe'. This is an unquestionably finer piece of literature, in terms of literary style, yet the books are not really comparable, because Stephen's work is rooted in the traditional values of the Golden Age of Victorian mountaineering, whereas Mummery's represents something entirely new in its bold modernity, far ahead of its time. And Mummery's final paragraph remains one of the great classics of mountain literature:

'Happily for us, the great brown slabs bending over into immeasurable space, the lines and curves of the wind-moulded cornices, the delicate undulations of fissured snow, are old and trusted friends, ever luring us to fun and laughter and enabling us to bid a study defiance to all the ills that time and life oppose.'

Like you I was surprised that Whymper's book wasn't mentioned. I also wonder if there aren't classics of the same period in other languages although all the French Alpine classics that spring to mind are much later (Rebuffat, Terray etc). Is there anything in German or Italian ?

I don't think there are any remotely equivalent books from French, Italian or German mountaineers in the nineteenth century – largely because they (amazingly) took little interest in Alpine mountaineering until the beginning of the twentieth century. The Duke of Abruzzi (an extraordinary, larger than life character), who made the first ascent of the Zmutt Ridge of the Matterhorn with Mummery, and later - in 1909 - led an expedition (the first?) to attempt K2, never wrote any kind of book on his mountaineering exploits, as far as I know.

I would rate the Mummery Crack as 4c, even with no protection, as you're safely wedged in there. I've never climbed 5b in my life, and it wasn't a problem in stickies, (but I had failed in big boots previously). I would rate the Venetz Crack on the summit block as much, much harder, more exposed and unprotectable until the overhang at the top, - I don't think Mummery ever led that.

And I think Mummery's book is much better than 'Scrambles', Mummery was a visionary and inspired me 40 years ago to explore and enjoy the Alps, not for ticks but for the 'Pleasures'.

Guido Lammer was active in this period, but his Jungborn – Bergfahrten und Höhengedanken eines einsamen Pfadsuchers was published in the 20th century.