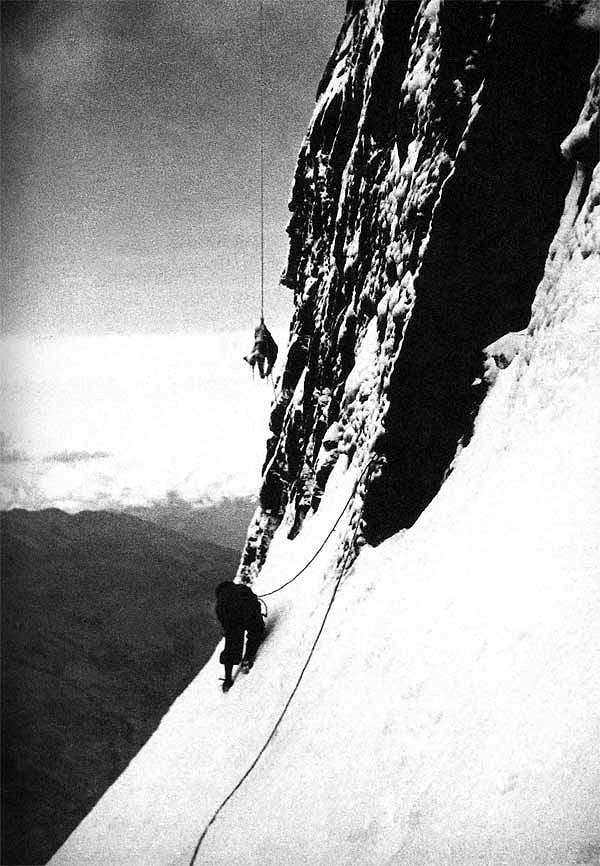

Rettner's latest book 'Eiger - Triumphe und Tragödien 1932 – 1938' is likewise founded on meticulous research. In it he documents the period of the earliest attempts on the North Face, with fresh information on the tragedy that befell Toni Kurz, the revelation of an extraordinary solo attempt which predated the first ascent in 1938, and a wealth of revelatory photographs – poignant records of human frailty and courage.

Eiger - Triumphe und Tragödien 1932-1938 was reviewed at UKClimbing.com by violentViolet here.

Luca Signorelli writes:

"Rainer, is in my humble opinion, today's greatest writer of mountain history. He's a great writer and a great historian. His book (with Daniel Anker) on the Corti tragedy of 1957 was an amazing achievement, and I think that "Eiger -Triumphe and Tragödien" will even surpass it. It's really a new generation of mountain histories, something I think is needed at long last."

I talked to Rainer about his fascination with the Eiger and his latest book:

How did your love of the mountains begin? And in particular, when did you first fall under the spell of the Eiger?

Well, back in the 1970s we spent our holidays in different regions of Switzerland. Our first visit in 1973 took us to Grindelwald. Being just 6 years old I was deeply impressed with this beautiful landscape and the huge mountains surrounding the village and yearned to go back.

I first got really interested in the Eiger during some boring school holidays in 1981 when I found a copy of the “White Spider” on my father's book shelves. The story of the North Face was very exciting and Heinrich Harrer instantly became my hero. Subsequently I started to buy books by other writers, like Toni Hiebeler and Arthur Roth, to learn more about the history of the Eiger. That's basically how it all started!

In telling the political background to the story of the first ascent of the North Face, you document Heinrich Harrer's involvement with the Nazis. Did you ever feel disillusioned as you uncovered the extent of that involvement, or were you able to still regard him as a hero, albeit a hero with feet of clay?

First of all, it wasn't me who uncovered Harrer's Nazi past. Gerald Lehner, an Austrian journalist, found his 80-page-thick file in the German military records which were held in the National Archives in Washington. That was in 1997. Looking back it surprises me that his involvement with the Nazis wasn't documented much earlier. There are several newspaper articles from 1938 in which he is clearly titled as a member of the SS. I do wonder why no one dug more deeply into Harrer's past before Lehner. Perhaps because this is still a very difficult issue in Germany and Austria, especially when it comes to criticising well known people like Harrer. Even now, more than two years after his death, he is still very popular in Austria.

Harrer definitely was a Nazi by conviction. He was a member of the SA, the SS and the NSDAP (The party of the Nazis) before the Eiger. He even had a swastika flag in his rucksack during the successful ascent of the Eigerwand, which was fixed on his tent in the preceding days. This is visible in a photo which is printed in my new book. Do I resent him for being a convinced Nazi? Well, not really. It's easy to be highly critical of someone 70 years later when you didn't live through that era. What would I have done back then?

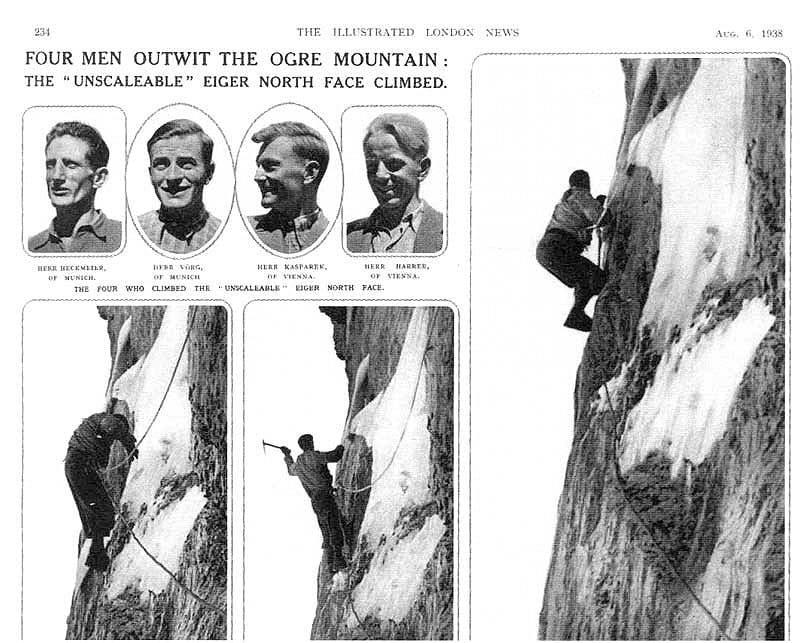

The really disappointing aspect of Harrer was his reaction after his dark past was uncovered. He never once made a really self-critical statement; his memory seemed to be very selective. He denied some facts until his death — for example his membership of the SA and the swastika flag in his rucksack. It's sad that he couldn't admit his mistakes. That said, his merits on the Eiger are indisputable. With his book “The White Spider” he added a lot to the myth of the Eiger. It's one of the classics of mountain literature, though it has its flaws. And he played an important role during the successful first ascent. But I definitely consider Heckmair to be a far more sympathetic and modest man.

In contrast to his writing about the Corti-Longhi tragedy, where he treated Claudio Corti very badly, Harrer did quite a good job in his chapter about the tragedy of Toni Kurz and his ropemates, but he missed a few details. Neither Albert von Allmen, the tunnel guard, nor the Swiss guides knew exactly what had happened when they talked to Kurz on July 21st 1936. The communication on that day was very difficult due to the weather conditions, and it was impossible for them to understand what Kurz was shouting. They just knew he was in trouble, but they did not know that three climbers were already dead, when they first contacted him. They heard Kurz shouting something what could mean “Drei Mann tot” (three man dead) or “Kein Mann tot” (no one is dead). The conversation that Harrer describes actually took place in the early morning hours of the 22nd July.

Harrer also left out this very important fact you mentioned in your question: that the guides had this one long rope – 60 meters – with them. Hans Schlunegger just put it between his back and his rucksack (not into his rucksack!) to save some time. That was something that was not unusual. When he made a sudden movement the rope dropped and fell down to the foot of the wall. It was a very unfortunate thing to happen: Kurz could have survived, because if the guides had had the long rope for Kurz to haul up, they wouldn't have been forced to knot two 30-Meter-ropes together. And this knot finally stopped Toni's abseil. But: I am sure that Kurz was in an overall desperate condition, so even if he had managed to abseil to the guides, it is not certain that he would have survived the difficult traverse back to the gallery window. In Harrer's defense: Arnold Glatthard, the guide from Kleine Scheidegg, who joined the Wengen guides on July 22nd in 1936, first told this story in an interview with a Munich journalist in 1996. That is – for me – an indication that the loss of the rope was quite a sensitive issue. There is not a single contemporary article which mentions this important fact! On the other hand there is no reason to blame the Swiss guides for that. They were excellent alpinists who did everything possible to save Toni Kurz. It was just bad luck!

Whilst researching the book you made the startling discovery that there had been a solo attempt upon the Eigerwand in 1937?

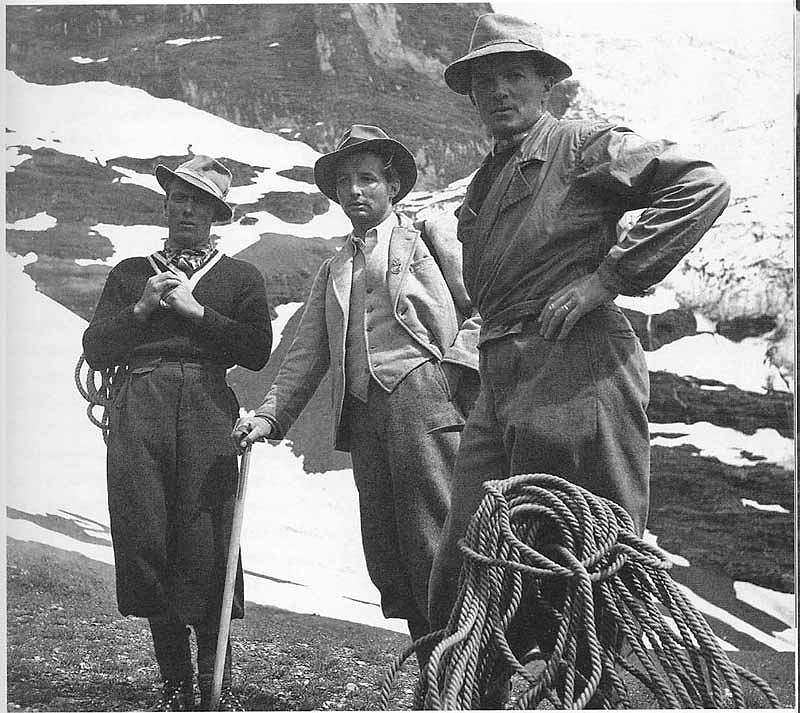

It's a mysterious story! While researching for his book on Climbing in the Swiss Jura, Swiss climber and author Claude Remy was told by a former rope mate of Hans Haidegger, that this excellent rock climber once told him that he had made a solo on the Eigerwand - up as far as Death Bivouac! Haidegger (1913 – 1991) was born in Austria, but had lived in Switzerland since he was a very young child. He was certainly a very good mountaineer, making first ascents on several difficult faces in the Bernese Oberland, such as the North-West Face of the Schreckhorn or early repeats (North Face of the Lauterbrunnen Breithorn, second ascent) with terrain similar to that of the Eigerwand. He never published an article about his Eiger solo, but made a short note in his journal (he always only made such short notes!), which his daughter provided me with, and it said: “Eiger Nordwand besuch abgestattet allein”, which means “Eiger Northface made a visit solo”. His ascent apparently took place in early August of 1937. He later drew the route he chose in a photo of the Eigerwand that was printed in one of Toni Hiebeler's Eigerbooks (published in 1973). According to that, he avoided the Difficult Crack and the Hinterstoißer-Traverse and reached the First Icefield in a direct way. It is unknown if this was intended to only be a recce climb or if he wanted to climb the Northface up to the summit. Only a few days after his solo he nearly made the second ascent of the North-East Face of the Eiger along with Lucie Durand, but bad weather forced them to reach the Mittellegi Ridge at a height of about 3.650 meters.

I can only speculate why he didn't publish an article on his daring solo on the Eigerwand: The Swiss press was highly critical at that time of any attempts made on the Eigerwand, especially if Swiss climbers were involved. Loulou Boulaz from Geneva– she was a member of the team that made the second ascent of the Croz-Pillar on the Grandes Jorasses – was bashed by Swiss journalists after her failed attempt on the Eigerwand in July1937 for being as unreasonable as the German and Austrian climbers! Maybe Haidegger – who was granted Swiss citizenship in 1942 – was scared to be badmouthed, too.

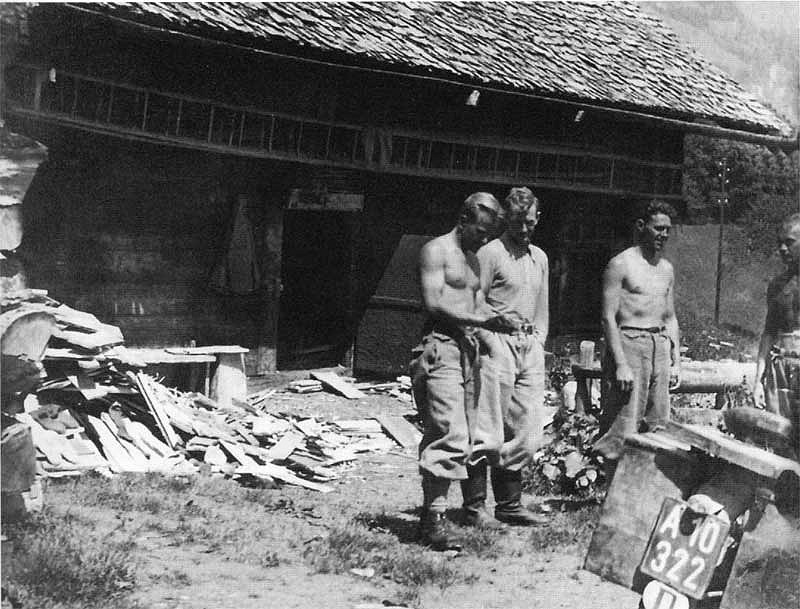

Your latest book is packed with photographs, many of which will be quite new to your readers? (More stunning photo's below)

I think so. Many of them have never been published in a book before, some of them only turned up in old magazines or newspapers. I was amazed by the support of relatives of some well known Eiger climbers such as Anderl Hinterstoißer, Max Sedlmayr or Leo Brankowsky, who provided me with some stunning photos. I was given an extraordinary photo album with over 100 pictures from a member of the Munich Mountain Guard, who helped to retrieve the bodies of Toni Kurz and his comrades. Also I could choose from the full set of pictures that Ludwig Vörg took on his 1937 attempt with Hias Rebitsch. And I have to mention the photos of Hans Steiner, a photojournalist from Berne, who took shots of the successful climbers on 24th of July 1938 during the celebrations at the Eiger glacier station. So I certainly hope that the readers will like our selection of about 200 photos!

I'm sure they will, Rainer. I hope your book is translated into English very soon, it is clearly full of new information on what is inarguably one of the most important and engaging episodes in mountaineering history; it deserves the widest possible audience.

Many thanks for your time!

A brief history of the Eigerwand

The Eigerwand, or North Face of the Eiger, is one of the most notorious mountain walls in Europe – a mile of vertical rock and ice, wracked by rock falls and avalanches, and subject to sudden and intense storms. Early attempts to climb it ended in tragedy. In 1936 Toni Kurz was one of a party of four men who were forced to retreat in appalling weather from high on the mountain. Willy Angerer, Edi Rainer and Andreas Hinterstoißer all died; Kurz initially survived. A train tunnel cuts through the mountain; it has a gallery window opening onto the wall. An attempt was made by mountain guides to rescue Kurz by traversing the face from this window, but he was too high above the guides to be reached. Despite extensive frostbite he was able to cut the rope free from the body of his dead friends, then unravel it and drop down a strand, to which the guides attached a rope which he pulled up. However, the rope was too short, so the guides knotted two ropes together. Kurz successfully abseiled to within feet of those trying to save him, but the knot in the rope jammed in his krab and he died, still out of reach.

This tragedy forms a chapter of the book, 'The White Spider', written in 1958 by Heinrich Harrer, one of the team who in 1938 made the first successful ascent, the others being Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg and Fritz Kasparek. Harrer also devotes a chapter to a later tragedy: in August 1957, two initially separate teams were attempting the face – the Italians Stefano Longhi and Claudio Corti, and two Germans, Günther Nothdurft and Franz Mayer. They joined forces, but got into severe difficulties. Both Italians fell, were injured, and had to endure awful weather on different ledges, unable to climb on. The Germans successfully completed the ascent, but died during the descent. Longhi died on the face. But Corti was saved by human courage and ingenuity: an international group of mountaineers had gathered at the top of the mountain. They lowered Alfred Hellepart 1000ft down the face on a steel cable. He successfully located Corti, and brought him up strapped to his back.

In 'The White Spider' Harrer rubbishes Corti's mountaineering skills, and implies that his version of events is dishonest. He apparently believed that Corti had murdered the Germans to steal their equipment and food. Four years later the discovery of the German's bodies conclusively proved that they had died on the descent, and that Corti was completely innocent of any involvement in their deaths, but even then Harrer did not retract or apologise.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Alpine Introduction - By Rich Cross BMG - Click here to read

Dolomites and the Weisshorn by Alan Heason- Click here to read

Epic on the Badile - An article from the 1963 Tuesday Climbing Club Journal by Mike James - Click here to read

Alpine Reminiscence 2007 by Nick Bullock - Click here to read

Climbing with Sir Ran Fiennes - The North Face of the Eiger by Kenton Cool - Click here to read

Staying Alive This Winter by Andy Kirkpatrick- Click here to read

Eiger - Triumphe und Tragödien 1932-1938 by Rainer Rettner: reviewed by violentViolet- Click here to read

My Eiger North Face Story by David Gladwin- Click here to read

About Kate Cooper:

Dr. Kate Cooper is a writer, property renovator and maths tutor living in Leeds, West Yorkshire. She climbs whenever work and family commitments allow, and occasionally when they don't. She is the author of 'Rock Climbing' (publishers TickTock), a photo-packed overview aimed at giving 10 – 14 year olds some insight into what climbers do.

Comments