The approval of a series of hydro power schemes in Glen Etive has dismayed many in the outdoor community. But is the opposition justified or proportionate? Tomas Frydrych has his doubts. At the root of the objections, he suggests, is a misconceived notion of wildness that serves us poorly in a time of global environmental crisis.

Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity

In the contemporary outdoor world 'wild' is all the rage. Hardly a day goes by when the above quote, or similar, doesn't appear somewhere in our social media feeds, while everyone seems to be #rewilding this or that (or at least knows someone who is, or is about to be). Yet, not many of us seem to have given much thought to what we mean by wildness, and what in turn it means for us, both individually and collectively, beyond that 'out-of-civilisation' feeling. Look into that pond, and all kinds of things start staring us in the face ...

Call of Wilderness

The idea of wildness as we know it goes back to the 19th century romantic movement, and as such bears all its hallmarks – an intense individualism, an obsession with aesthetic, an idealisation of the past and the elevation of emotion over reason.

The romantic nature is about escaping the reality of the civilised world, and wilderness becomes a shorthand for an idealised, would-be primaeval space - one which, as an antithesis to civilisation, is fundamentally defined by perceived human absence. With 'perceived' being the key word: the romantic wilderness is not an objectively defined reality out there, but rather a quality of experience, delimited by individual expectations: the romantic's wilderness is little more than a subjective aesthetic quality.

More so, the romantic observer is never bound by the demand on human absence. His or her activities are justified by the experiences they create, while at the same time this inherent entitlement excludes others – the wilderness perspective is profoundly self-referential and egocentric. This cannot be overstated: the romantic wilderness is primarily about the individual's self.

While romanticism as a movement has long passed into history, among us outdoor folk it has kept a firm footing, and the contemporary UK discourse on the wilderness subject is permeated by it. Common folk and influencers alike, when we talk about 'wildness' and 'wilderness', we invariably talk about little more than an aesthetic, the things we don't want to see (paths, fire rings, wind turbines, dams), and the things we want to see in their place, scenery.

The debate around the proposed Glen Etive hydro schemes has brought this into a sharp focus for me. There are many ways to describe the glen – beautiful, scenic, dramatic – but one thing it is not is 'wild'. Humans have shaped this land for centuries: the glen is home to people and timber plantations, its hillsides are overgrazed by sheep and too large deer numbers, the high ridges are marked by walls, fences and cairns. And, not least, the river banks are systematically damaged by parked cars and the detritus of happy campers coming to experience 'the wild'.

But what strikes me more than anything about the whole situation is the intensity of the response from us outdoor folk. The thing is, the impact of these schemes is going to be almost entirely visual rather than ecological. Scenery is not without value, but we are deluding ourselves if we think that our concern for preserving scenery is about nature and the environment.

I am, by no means, wanting to argue for the Glen Etive hydro, but I am questioning our collective priorities. There are far bigger issues facing our 'wild' land today; next to the biocide that is taking place for the sake of driven grouse shooting, micro-hydro pales into utter insignificance. It is estimated that as much as 20% of Scotland's landmass is affected by the grouse industry, yet it seems somehow harder to whip ourselves up to the same level of passion to address this travesty once and for all. Perhaps it's the sight of all that heather in bloom?

But, surely, some places are special?! Why, because they photograph well? The real question is what makes some places not special enough to care, for the two go inseparably together.

Rewilding Makeover

The wilderness idea received a makeover in the 1990s with the birth of the rewilding movement. While the term is nowadays commonly misapplied to all kinds of things, the original concept is simple, based around the three Cs: create large areas of strictly protected wild land 'cores', interconnected by 'corridors', with ecological processes solely driven by keystone species, and in particular large 'carnivores'.

The rewilding ecological model is often presented as a panacea; in reality it has both strengths and weaknesses, but that's a discussion for another time. What I do want to note here is that rewilding is firmly rooted in the old romantic tradition, retaining its basic premise that humans don't belong. What changes, however, is the strength of that conviction and the scale of the aspirations: while the old preservationism was about creating monuments dedicated to wilderness, rewilding is about continental-scale wilderness, effectively containing humans in reservations surrounded by buffer zones of 'compatible activity' that stand between them and the 'real' nature.

This is not overstating the case, to the contrary; the views of rewilding's founding father are well documented. If nothing else, Foreman's vision of human population reduction down to 2 billion begs the questions of how and who decides which 3 out of 4 of us don't deserve to live. This is the basic philosophical perspective from which rewilding was born, its cultural heritage.

Wilderness Ethos

The exclusion of humans from nature as some sort of an alien species is incongruous, and nothing makes this incongruity more self-evident than rewilding's obsession with large predators, that is, large predators but one – this exclusion is an a priori philosophical choice, not an ecological one.

And this basic tenet of the wilderness perspective has two major consequences. On the one hand it produces a rather cavalier attitude to those who happen to stand in the way. I have already touched on some of this, but it is worth noting that these attitudes go right back to the old romantic roots.

When we celebrate Muir and his compatriots for the creation of the US National parks, what we don't talk about is that this 'pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people' was created by the violent dispossession of their native inhabitants. Somewhat ironically these peoples shaped this land for thousands of years, and yet in the wilderness dream it inspired there was no place for them. This historical wrong has never been righted, and, in my book at least, no amount of 'enjoyment of the [read: right kind of] people' can make up for it.

Nor is this something that is merely a problem of a different age and place. The same attitudes crop up right here in the UK today, whether it's the lack of social impact assessment for the Kielder lynx trial, the refusal to use fences in Assynt, or the discussion around the future of the Cairngorm ski resort.

But this view of humans as not belonging creates another problem: it fosters the view that nature is something reserved for the weekend, for the designated, protected wilderness out there, while here in our urban ghettos it's planet-wrecking business as normal, because some places are not special enough to care. And as long as this is the case, the real nature doesn't stand a chance.

Climate Change

Not to beat about the bush, an obsession with wilderness breeds Climate Change denialism. In some cases this is quite explicit, e.g., among the hardcore rewilders, but even when it is not, it frequently hides just below the surface; scratch that and it bubbles up in no time.

Climate Change is not something that is on the horizon, something that is about to happen, something theoretical. It is happening right now, and it is a matter of survival of the entire ecosystem of our planet. And we only have a handful of years to get on the top of it.

Climate Change modelling shows that there is a point of no return. Beyond it the deterioration of the planet's climatic conditions will rapidly accelerate into a full-blown global catastrophe. A study published last year in the Earth System Dynamics journal calculated that we will reach this point by 2035. It gets worse: that calculation is based on the assumption that the percentage of energy produced from renewables worldwide will grow by 2% per year. On present trends this is way too optimistic.

And, of course, this would not fix the problem. Even if we push this up to 5% growth, it will only buy us an extra decade. What is really needed on this front is a complete switch to energy generation with low CO2 emissions now, and also significant carbon capture, for raw energy is just a part of our carbon footprint.

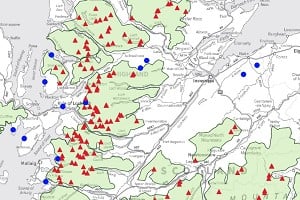

In Scotland (where we do lot better than the UK as a whole), we currently generate just over 2/3 of our energy from renewables, and around 2/3 of that from wind. So to generate all our energy from renewables we will need half again as many of these renewable installations, and I expect also a shift toward a much higher percentage energy from hydro. And these need to go somewhere (btw, there is no point pinning our hopes on the technologies that are not yet ready, like tidal, we need to be implementing solutions now).

The bottom line is that I can't say I care about Climate Change, laud the school kids for their strike, and then systematically object to every single renewable project out there because it offends my sense of wildness, because it spoils my photos, or even because someone else is going to be making money out of it. And we outdoor folk, and the NGOs representing us, invariably do.

I'll be quite honest, I have an intense dislike for wind farms, for the fact that nowadays it is virtually impossible to look from a Scottish hill and not see them in every direction. But there is a bigger picture here, which I am learning to see – Climate Change really changes everything. (Of course, it's not just the renewables, we could talk about commercial forestry, but I shall leave that for another time.)

Conclusion

To come back to the opening quote, I understand and relate to what Muir says – I too find respite in mountains and woods and am happy to wax lyrical about it. The wilderness experience is like a good fiction book – there is nothing wrong with enjoying it, immersing ourselves into it. But if we only look at nature through the wilderness lens, we end up with fictional, oversimplified, narratives that haven't served us, and the planet, particularly well in the 117 years since those words were written. The idealisation, and idolisation, of wilderness skews our perspective, detaches us from reality, allows superficial preferences to masquerade as environmental concerns. It's not enough. There is a much bigger picture out there, and closing our eyes to it doesn't make it go away.

- OPINION: The Trouble with Social Media in the Outdoors 27 Aug, 2018

- OPINION: How Green is Your Gear? Not Very 23 May, 2018

- OPINION: Sustainability in the Outdoors Depends on Fair Shares 27 Feb, 2018

- OPINION: Microspikes - Use with Care, or Not At All 10 Nov, 2017

Comments

I have to admit that when the author used 'wildness' then 'wilderness' interchangeably in the first couple of paragraphs, it skewed my reading of the rest. In the modern environmental sense, wilderness is a specific thing, with an accepted specific definition, something along the lines of 'a large tract of land almost completely devoid of human activity or structures'. Of course we can joke about the garden being a wilderness, or our son's bedroom, or an empty restaurant, but this article seems to be trying to take on larger more serious environmental questions.

Plenty of places in Scotland are wild, they exhibit wildness for the human observer. I doubt there is any wilderness in Scotland, with all those roads, villages, farms, fences, signs etc. I just checked on Google Earth and in the biggest 'blank' spot with no towns or roads has two hotels 30km apart. That ain't wilderness.

I do see the term used - incorrectly - there for marketing reasons and in many other places that are basically just 'outdoors'. But this is a misuse of a term - not a problem with the term itself.

This is not just semantics, definitions matter, because the nature of the subject, particularly in this case its size, matters. There are very good reasons, particularly biodiversity (a term notably absent from this piece) why wilderness must be both empty of humans and large.

Issues of land use in Scotland are a poor place from which to be criticising - and devaluing - the concept of genuine wilderness.

I don't have much to do with Glen Etive, but I read the arguments with interest because I think it's a question that will come up again and again: how much of our 'natural' environment should we be willing to sacrifice to offset the effects of climate change. Most of what I read understood that there was a balance to strike, but that ultimately the benefit of the Glen Etive hydro schemes seemed very small compared to the disruption they will cause. The article ignores all of this nuance with sentences like:

The bottom line is that I can't say I care about Climate Change, laud the school kids for their strike, and then systematically object to every single renewable project out there because it offends my sense of wildness

The Glen Etive scheme is not 'every single renewable project'. In fact, it's the only one that has received this level of scrutiny that I'm aware of.

Having discussed at length the sentimental and irrational aspects of people's attitudes to the countryside, the author doesn't mention any of the effects of the Glen Etive scheme, either in terms of energy produced / CO2 saved, the impact on ecology or even the economic arguments of hydropower vs tourism. But I guess it's more fun to sound superior rather than debate the issues raised by the scheme.

Provocative, and I don't mean that as a criticism. However, generalised and binary arguments (either addressing the potential climate catastrophe or enhancing wilder landscapes, not both) are unhelpful. A few points:

1) "The bottom line is that I can't say I care about Climate Change, laud the school kids for their strike, and then systematically object to every single renewable project out there because it offends my sense of wildness, because it spoils my photos, or even because someone else is going to be making money out of it. And we outdoor folk, and the NGOs representing us, invariably do."

This statement is simply not true. Far from objecting to 'every single renewable project', Scottish NGOs such as the John Muir Trust, Mountaineering Scotland and the North East Mountain Trust have objected to relatively few and have been very careful in this regard. In respect of small scale hydro, the major concern in most cases has not been the schemes per se but the poorly constructed, poorly restored and, on occasions, unnecessary tracks to these. The NGOs have mainly been concentrating on trying to get the tracks issue dealt with properly, not trying to stop the development of the schemes (many view Etive as an exceptional case).

The NGOs have been at the forefront of supporting the extension of native woodland and encouraging peat restoration. Apart from the other ecological (and landscape benefits) of these, forests and peatland are major carbon sinks.

2) The article lacks context. All reports argue that urgent action is needed across a range of fronts. Onshore wind and hydro are one part of a jigsaw that includes the development/extension of other technologies such as off shore wind and solar. Also the article makes no mention of the urgent need to reduce carbon use, for which we all have a responsibility.

3) Personally, I have shares in wind farms, hydro and other renewable technologies but have objected to applications for certain schemes because of their locations: I see no paradox in this.

4) To finish with a provocative note of my own- climbing can be a carbon intensive activity. How many of us are planning to climb in ways which reduce our carbon footprints from travel?

Why does biodiversity necessitate the absence of humans and where do you put those humans you have removed or not allowed to live there?

As I understand it part of the idea behind the piece is that we need to live better with nature, rather than seeing ourselves as somehow removed from it.

Yes, we are part of nature, but that doesn't mean we have to inhabit and scar every single bit of it.

Biodiversity does not necessitate the absence of humans, but large areas of intact, undisturbed ecosystems are important for preserving biodiversity. Beneath a certain size, they collapse.