The 1996 Everest season saw the worst loss of life on the mountain to that date, as large guided parties with big stakes in success were caught in a storm at extreme altitude. Three bestselling books were written by survivors, Into Thin Air, The Climb, and Left for Dead, but these conflicting accounts may be most illuminating if read together, says Ronald Turnbull.

Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet doesn't count as a mountain classic, being set, as the name suggests, at an altitude of 9m. (That said, I did once reread the first volume, in French, when stormbound for two days in an Alpine hut.) Its relevance is that the first three volumes, instead of coming one after the other, tell the same story from three different points of view. But the mountain classic that I'm calling The Everest Trilogy not only goes 8837m higher, but a step further in literary terms too. It's written from three different viewpoints, by three different people.

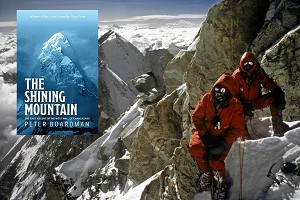

The three-volume work is set around the disastrous Everest season of 1996. And it makes a detailed exploration, not just of that often-described mountain, but of the rationale and morality of paid-for adventure. The basic storyline, for those not familiar: in 1996, Everest is entering its phase as mass holiday resort. Two guided parties are on the South Col route: Adventure Consultants, and Mountain Madness. Summit day starts well. But the climbers are slow, queues build up, and as they're all high on the mountain a killer storm moves in. On the South Col route alone, the focus of these books, two clients and three guides die and others are left horribly injured by frostbite (less well known is the loss in the same storm of three members of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police expedition on the northeast ridge).

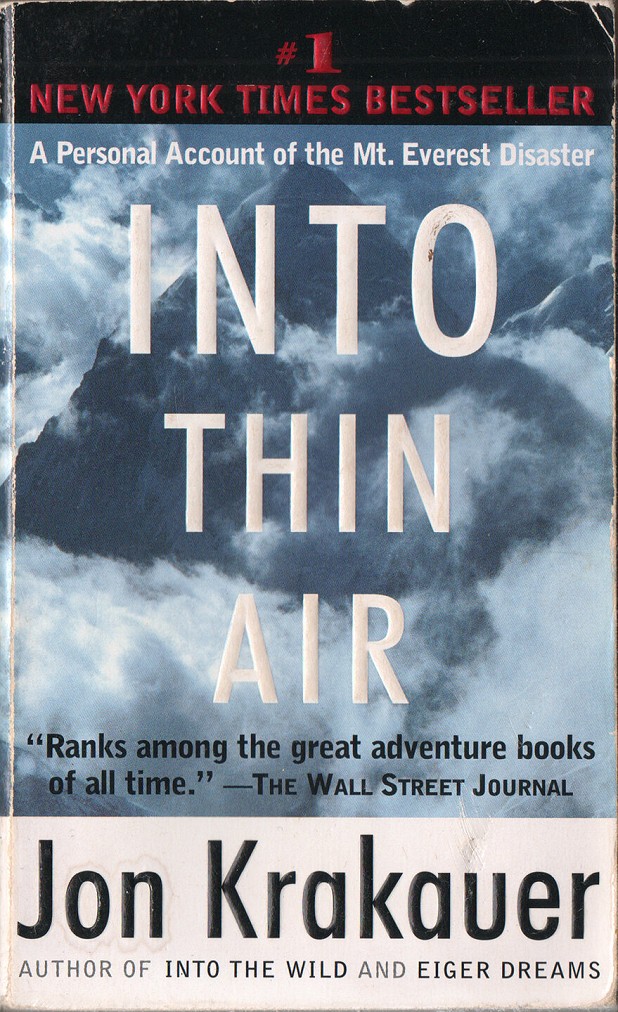

Volume 1, the 'Justine' as it were, is Jon Krakauer's 'Into Thin Air'. Now, climbers (with a few interesting exceptions) don't make up their expedition accounts from pure imagination. But they do turn them into stories. They have to, it's a necessary human instinct – not to mention they need a publishing deal to pay for the next expedition. And considered this way, as a story, the choice of Krakauer as the first protagonist is subtle and ingenious. Krakauer is taking part as a paying client, but he isn't actually paying. He's an experienced climber, on a commission for Outside magazine. So he not only knows far more about what's going on than a normal client, but also has the story telling skills to set it down.

The role of Tragedy, Aristotle tells us, is to induce pity and horror. Spot on. As in a Shakespeare play, subplots and main plots twine together like the strands of an old-style climbing rope. There's the 'sensible' Adventure Consultants party, led by Rob Hall, which Jon Krakauer is signed up to – contrasted with the 'wild' Mountain Madness party, led by Scott Fischer. First subplot: Doug Hansen the postman from Seattle. Turnaround time on summit day is 1pm – else your oxygen runs out and you get benighted. Hansen has already been on Everest once with Rob Hall, paid his $40,000, and been turned around at 1pm just short of the summit. He's scraped up another $40,000 and now he's trying for the second time. 1pm comes round again – and this time, Hall lets him go on. At 3pm they reach the summit – with the storm already rising up the mountainside below them. And at the Hillary Step, Doug Hansen can descend no further.

A terrible situation for Doug Hansen, but very nasty also for the guide who'd broken his own rule and encouraged him to go on up the mountain. Is this the reason Rob Hall decides to stay with his client, to join him in death as the storm sweeps up the mountain and night falls? He doesn't even die in private. He has a phone, for a last conversation with his wife back in New Zealand. And it's a satellite phone, so everyone else on the mountain listens in.

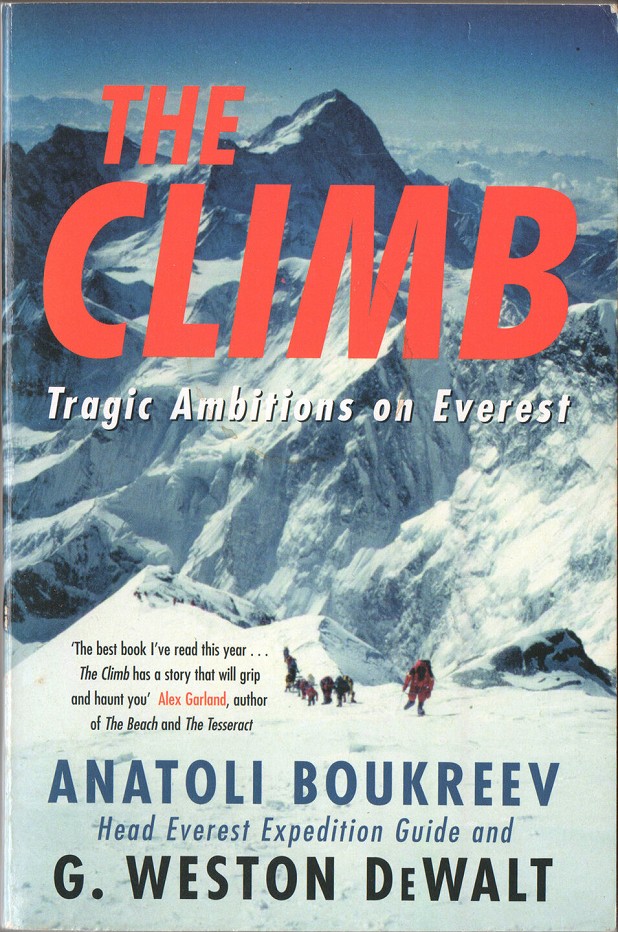

And is this even the book's main storyline? There's the chaos along the summit ridge, fixed ropes late in being laid, climbers queuing at the Hilary Step as their brains are quite rapidly dying. The Russian guide Anatoli Boukreev, inefficient because climbing without oxygen, neglecting his duty to his clients for the kudos of his own oxygen-free ascent.

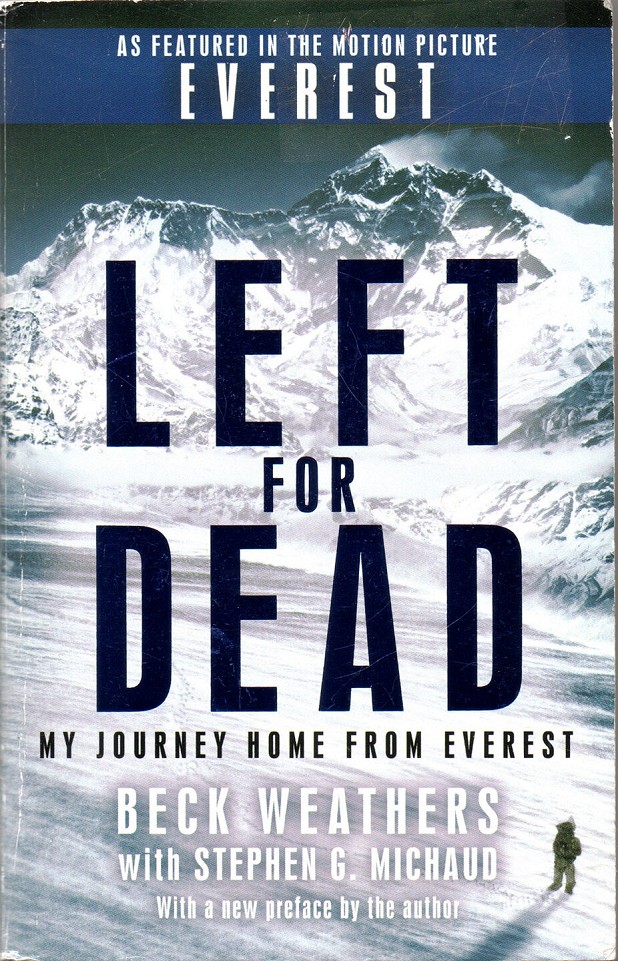

Then there's the moment the next day, when they rediscover the two clients left lying out on the snowfield of the South Col, 200m from the comparative safety of the tents. Beck Wethers from Texas, and Yasuko Nambo, who has just achieved her lifetime ambition as the second Japanese woman to complete the Seven Summits.

They're dying anyway; there's no way to move them. Even if they could be moved, there'd be no way to get them back down the Lhotse Face. Unlike Rob Hall 800m above, they walk away. They leave Beck and Yasuko out there in the snow.

Twelve hours later, as day breaks again, a bit of a surprise. Beck Wethers crawls into the tent.

Now what? He's still a dead man crawling. Do they put their lives at further risk by dragging him down the mountain? They leave him in an empty tent to finish dying…. But then in the morning he's up again, pulling on his crampons. Can they bring themselves to abandon him to die for the fourth time?

A particular trick for fiction authors is called the unreliable narrator. The author, and the reader, can work out that the voice telling the story is ignorant, or stupid, or she's just telling lies. This is hard to do when the author and the on-page 'narrator' are both the same person. Accordingly, the second volume has a new narrator. Anatoli Boukreev , the Russian guide from the Mountain Madness team and the villain of Krakauer's account.

An attentive reader might already have had doubts about Krakauer's Boukreev, the so-called 'irresponsible guide'. He was the one who went back up the mountain to look for Scott Fischer, and when that failed went out three times, in the night blizzard, and brought in three dying clients. Every one of the Mountain Madness clients survived the disaster, largely thanks to Boukreev and his colleague Neal Beidleman. In Boukreyev's account, 'The Climb' (1997, with G Weston Dewalt) he does without oxygen specifically to avoid the sudden descent into uselessness that hits not only the clients but also the other guides when the bottled oxygen runs out. Boukreev rewrites, reverses even, the storyline of Volume 1, turning its villain into one of the heroes. Just as Durrell's 'Balthazar' undermines and reinterprets all the supposed 'facts' of 'Justine'.

Krakauer's competence on the mountain, his compassion for the lost and dying: these are not in question. But neither is Krakauer's urge for a great story to bring back for his magazine.

Another of Rob Hall's clients, Lou Kasischke, wrote his own account 16 years later, calling it 'After the Wind'. Not all the clients were so obsessed with the summit: Kasischke was one of three who turned back at 11.30am, three hours below the summit and with no chance of making it by turnaround time. His story lacks a villain. But he does suggest that Krakauer's magazine commission caused risks to be taken to increase the count of summiteers for the publicity.

Graham Ratcliffe was one of the party that reached the South Col as the two fatal expeditions were coming down, and helped the survivors down the Lhotse Face. 'A Day to Die For' was published 14 years afterwards, and promises 'staggering, hitherto undiscovered facts' which, to be honest, I haven't got around to studying up on. His discovery that accurate weather forecasts were available to both expedition leaders rearranges the net of responsibility and blame.

The final pair of eyes looking at the story belong to Beck Wethers, the client of Rob Hall who was 'Left for Dead' on the South Col. Yes, the exhausted guides couldn't bring themselves to abandon him for the third or fourth time. After many difficulties he is helicoptered off the top of the Khumbu Icefall. And the loss of various bodyparts lets him look back in a new way at his earlier Everest urges. "I would have to portray the truth of my own deeply flawed soul… Mountain climbing as an obsession is a selfish endeavor, and there's no way to get around that fact."

The book is co-written with his wife Peach. "Beck seemed selfishly determined to either kill himself or get himself killed." His teenage daughter begged him not to go, and he'd promised her not to. When he went anyway, thus missing his 20th wedding anniversary, Peach decided that she was going to leave him. Peach turns into the real hero of the story, gathering funds, browbeating US senators, and arranging the helicopter that lifts him off the mountain. And so presenting another neat contrast, the Everest venturers against the skill and courage of the pilot, Lt Col Madan of the Royal Nepalese Army, putting his own life on the line as he takes a helicopter higher than one has ever flown.

Dying climbers: leave them to it, or rescue them up to the point where you die yourself? How much of this sort of adventure is actually about seeking status? Rounding off the set, 'Left for Dead' brings into even sharper focus the fundamental question. Becoming the second Japanese woman to complete the Seven Summits: is this a project worth dying for?

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan

- My Favourite Map: Geology Plus Glaciers 11 Dec, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mini Guide: The Cheviots 27 Feb, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

Comments

Thanks for the article

Please note that according to "Into Thin Air", Doug Hansen reached the summit after 4 PM, not at 3 PM as you said. Quite a difference. Thank you

Well, I've only read two of the three and am firmly in the Boukreev as hero camp. Krakauer is a better storyteller, but takes too many liberties and does Boukreev a huge disservice.

I've read all three, and am absolutely in agreement.

Krakauer is a great writer and his book is a classic, but he didn't understand Boukreev, his motivations and and why he made the decisions he made.

He made the wrong call in painting him as the villain when he should have been hailing him as the hero of the day.