Alan Heason looks back on and shares an essay that he wrote about a trip to Skye at age sixteen and a quarter...

I'd been sorting through wodges of old papers, as one does at a certain point in life, preparatory to shredding most of them as irrelevant, uninteresting or un-needed, when I came across a clip of hand-written pages of old school papers. I don't recollect reading through this one before. (I probably had, but there you go, memory…) It was an English essay on the subject 'what we did on our holidays', it was dated 1954; I would have been sixteen and a quarter years old.

The Misty Isle

A reek of fish pervaded the atmosphere as I sat on the edge of the jetty at Mallaig, my feet dangling lazily over the turgid swell of the Sound of Sleat. Slapping of riplets on the barnacled timbers merged naturally with the creak of a rope holding the M V 'Blaven' to the landing stage.

Small groups of people clustered together, limpid and drooping in the Scottish heat. Another quarter of an hour before we were due to leave – for Skye – the Misty Isle.

At last a plank was laid 'twixt jetty and boat and we capered across, waving our arms to retain balance. My rucksack was carefully stowed beneath a tarpaulin, and I reclined once more to regard the other passengers as they too embarked. One or two locals, three American tourists and a little girl with a doll, clutching her grandmother's belt. Two pseudo girl 'hikers' slithered aboard amidst squeals of terror and gasps of fear. They collapsed in the shadow of the wheelhouse and complained loudly to each other in refined Oxford accents about the precarious gangway they had negotiated. Then two strapping youths laden with outsize rucksacks edged aboard, proceeding to photograph every photogenic subject in sight. A fisherman jumped down to the deck followed by a further hiker, a bronzed girl who strode nonchalantly aboard and jettisoned a tremendous rucksack on top of mine.

A motor throbbed beneath us, a rope was thrown to the deck, the plank removed, and we were off – to the western horizon and Skye. How long I had waited to get there. How often had I imagined what it would be like. And at last I was on my way across the Sound of Sleat to it. In half an hour I would be at Armadale near to the grand Cuillin hills, every climber's Mecca. My camera was always ready, and I strode across to the bow in the hope of getting a view of the serrated Cuillins. Only a few of the highest peaks protruded above the nearer lowlands and I remarked to the girl who was also standing there that it was not worth snapping.

She was a climber too, that was obvious from her boots, clothing and general appearance.

'Are you going to the Cuillins?' I queried. 'Yes, climbing. Are you?' 'Yes.' and so we fell to discussing various topics on the subject.

A little later a sailor came around to collect the fares. 3/6d single, no return. We lightened our purses and resumed our discussion. Only a few hundred yards and Skye would be ours. We would tread its magic surface. It would be a dream no longer. It would be a reality.

Huge tyres were squeezed painfully between the hull and the landing stage and we strode onto the wooden pier to be confronted by a thin man who wanted a further 2d. 'To land' he said.

Striding across a sandy spot we sighted a small bus to take us from this desolate spot to Portree, or Sligachan en-route. A red-faced little man promised to look after our rucksacks but asked that we lifted them into the boot. Opening a map, we saw that the only road followed the coast, a circuitous route of 25 miles. 'Six shillings should be plenty for that' said Margaret, for that was her name. A Scottish accent quickly corrected her. It was the driver-cum-conductor-cum-guide. 'Och noo, it'll be costin' ye eleven shillings return,' He informed us. I stared, aghast. That was practically all the money I had. I paid up unwillingly and we settled down to get our money's worth from the delightful panoramas that revealed themselves as we rounded each bend. Although marked as an 'A' road, the track that we floundered along would have disgraced an English bridle-path. Never more than 12 feet wide it curled crazily over hills, down precipices, along beaches, through streams by poverty- stricken hamlets and beneath roaring waterfalls.

After reassuring ourselves that this was the right road we lazily stretched our legs and pointed out to each other various sights of interest: a husky farmer wearily scraping peat from a bog and adding it to an already-overladen donkey cart pulled by a tiny pony; or glimpses of the Cuillins. Blaven towered above us, its crags gleaming dully in the mid-day sum, patches of snow still nestling in shaded hollows. Sheep wandered haphazardly across the road, jumping aside only when almost underneath the wheels of the bus. And so, in this exciting and bumpy way, we arrived at Sligachan after a 2-hour run. Heaving out our rucksacks we held further council as to which would be the best way to Glen Brittle. A lady at the climbers' hotel informed us that the next bus was at quarter to four, in two and three-quarter hours' time. We decided to walk. As I was returning the next morning I dumped half of my kit in the foyer of the Sligachan, the most renowned hotel for climbers in Great Britain. Sharing out our kit equally we move off once more up the rough road for half a mile then turned left up a well-marked path which, according to Bartholomew's map, led over the col we could see in the distance to Glen Brittle, about 12 miles away. Our path led us by a mountain torrent, only flowing with half of its usual force, nevertheless breath-taking in its beauty.

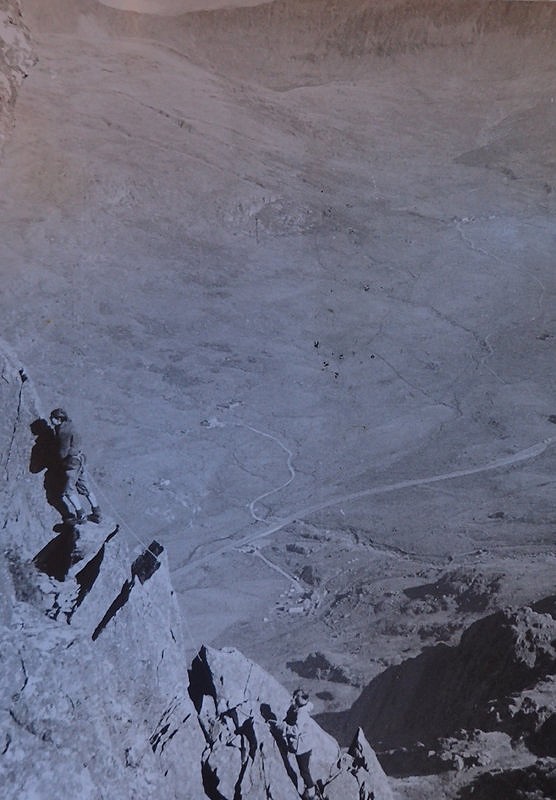

An hours' climbing brought us to a large waterfall, at the top of which was a large stone platform. Here we rested for a while, washing the grime from our faces and refreshing ourselves with ginger beer and date and walnut cake purchased in Mallaig that morning. However, time was pressing, and we resumed our upward toil to the col. Sligachan hotel was an insignificant white blob beneath our feet. The coast was visible, the ethereal blue of the waters of the Sound of Sleat glimmering fantastically in the hot sun. Beyond that rose the mountains of the mainland, brown, purple, black, intersected by many grim lochs, fed by silver streams. Leaving behind this marvellous vista, we strode across the plateau, marvelling at the weird formations of the Cuillin peaks rearing skyward to our left. Glen Brittle was suddenly revealed to us in its glory far beneath as we rounded a boulder. Not a grim cleft as we had imagined, but a broad valley, a river meandering lazily across it to the blue sea beyond. Down the tussocky hillside we strode, chewing Mars bars, delaying the pangs of hunger. Down on the road we walked even more rapidly, for a large black cloud bank towered behind us: rain.

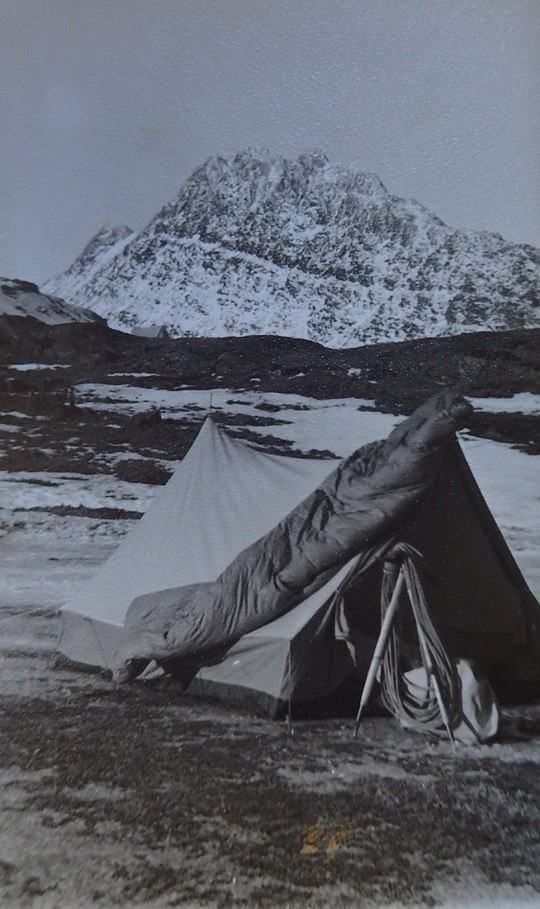

Glen Brittle youth hostel came into sight just as the rain fell and we took refuge inside for about twenty minutes. Three miles further along the road we passed a tiny hamlet which we knew was only half a mile from the sea-front where we were to camp. A green sward rose gently before us, and the tang of a sea breeze wafted through our nostrils as we came to the camp ground. Seven tents were there already but of their inhabitants there was no sign. Obviously, they were climbing in the mountains high above us. Rapidly we pitched Margaret's tent, a Blacks 'Tinker'. Just as we had finished the climbers returned, one of them being a friend of Margaret. Alan – for that was his name – brewed me a cup of tea and made soup and fed me, while Margaret retraced her steps to the hamlet we had passed earlier to purchase some provisions. I met her returning, carrying a tin of milk, some eggs and a loaf and sundry other edible items. The provisions van, which calls once a week, had been there so she stocked herself up with food generously.

Squeezing inside her tiny tent, sheltering from the drizzle, we cooked a splendid meal on our two stoves, my 'Optimus' and Margaret's 'Burmos'. New potatoes, peas and macaroni with cheese were followed by sardines on toast and mugs of tea and coffee, plums and custard and sweets. By this time the sun had reappeared, so I washed up in a nearby stream while Margaret tidied up and we strode off, in high spirits, toward Sgurr Alasdair. It was 8pm. I carried my rucksack as it was my intention to carry on over the ridge, down to Loch Coruisk, along its banks and over the ridge to Sligachan hotel in time to catch the 8:15 bus back to the ferry.

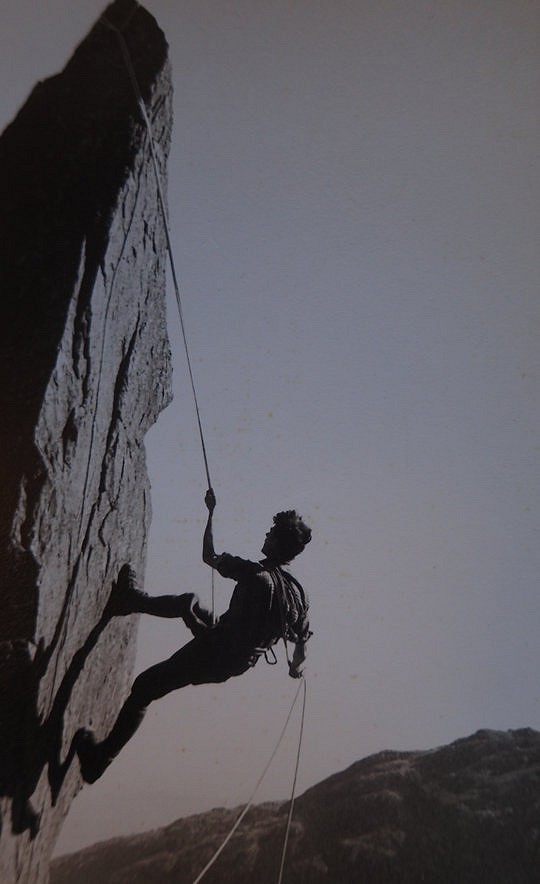

Happily, we strode up the steep hillside, over streams, until we reached the mountainside. Far below we saw the camp, and Glen Brittle unwinding northward. We decided not to climb the Sgurr Alasdair stone shoot as too laborious and dangerous, so we cut off at a tangent across the mountainside onto a wing rising almost to the summit of Sgurr Alasdair, the highest point in the Cuillins. Our intention was to keep to the ridge of the wing as that looked to be the most direct way to the summit. Complaining our way towards 3,000 feet we wearily stumbled up over 1,000 feet of scree which continuously shifted under our hot feet, causing a cloud of hazy dust to help choke us in the heat which hammered down on us from the brazen orb which hung low in the firmament. It was 9:30 in the evening yet the view westward and southward, flattened beneath us, revealed all the 'cocktail Islands', Rhum Eigg and Muck (so named due to their resemblance to the constituents of modern cocktails), most of the Outer Hebrides, Barra, South Uist, North Uist, Harris and part of Lewis, a thin ribbon of sea visible beyond them which must have been at least 60 miles distant. To the north most of the tormented needles of the Cuillins reared skyward, some of the highest enwreathed in mist, as was Sgurr Alasdair, our goal. Beyond these, visible through the saddles, were some of the major peaks on the mainland, shimmering in the haze. Yes, it was worth cycling over 500 miles to see, worth all the toil and effort, worth the wearying scrambles up the screes.

Again we scrambled upward, but the mist was cascading down close above us and Margaret decided to return, for it was 10 pm and no useful gain could be acquired by pressing on further. So she rapidly retreated down the rocks leaving me alone on the verge of the mist bank in complete silence apart from the rising wind squealing through the towers of rock surrounding me. A few more minutes of climb found me on the summit of the highest peak with a strengthening wind causing me to shiver slightly. Putting on extra clothes I ate a piece of Kendal mint cake to sustain me and struck off along the ridge. A phosphorescent light filtered through the wraiths of smoky fog allowing me to see the way sufficiently to make some progress. I turned left and slithered down small rocks, up steep steps, and clung to small handholds on breezy traverses. But not even in Scotland is there light all night, and a gloomy silence pervaded everywhere after an hour or two. Gusts of cold wind buffeted the thin ridge, howling eerily as the rain drizzled down uncomfortably. The ridge rapidly became more dangerous as I proceeded, so I unhappily decided to strike off the knife edge, down into the swirling cauldron below, at the bottom of which, I knew, steamed Loch Coruisk, the most deserted and wildly impressive lake in Europe. It is said that, because of the height of the peaks surrounding it, the sun never strikes its surface. A grim tale indeed.

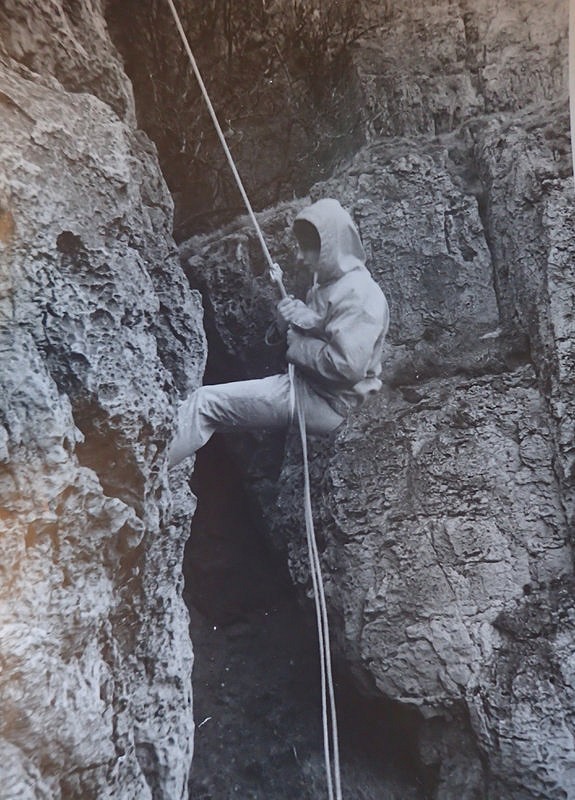

Easy going came at first, and I clambered down swiftly. Then came scree, quite an easy problem in daylight, but now, at 12:30 in the night, with a biting wind squeezing drizzle through my clothes, it was distinctly unpleasant. Clinging to slippery rock, I breathlessly clawed my way downward, a cascade of scree clattering deafeningly down below me. It was a peculiar sensation to hear that scree thundering down; I felt that I was disturbing the peace, and that at any moment a voice would ask me what I was doing, making such a hideous clatter on the mountainside. Clawing further down, I dislodged an extra-large rock which fell in ever-increasing bounds into the grim depths below. Crash. Crash. Slither. CRASH and the silence. About 5 seconds later dull 'thump' reached my straining ears. Obviously, the boulder had shot off the brink of some great precipice directly below me. I shuddered to think how I might have only found it by my legs suddenly finding no hold for my dangling feet.

Quickly I traversed to the right for about a hundred feet, then purposely hurled another brick downwards. This time it bounced down until I could only faintly hear it slither to a stop. And so, at the risk of tearing my clothes to pieces, I slid down the scree wildly, sometimes stopping for a few seconds to nibble at a little Kendal mint cake, and to sip a little concentrated orange juice. Suddenly an extra-strong breeze wafted the curtain of mist aside for a second and I saw a glimmer of water below me. Was it Loch Coruisk or some remote mountain tarn lying forgotten in its misty sombreness? Ten more minutes hurried scramble and I crouched by its brink. The mist was above me now, hiding the horrible descent I had just done. The tarn, for such it was, rippled oilily in the dark, damp atmosphere. Rain speckled its surface gently, striking through my clothes at each thrust. But now, having come down the worst part, I actually began to enjoy this crazy escapade in the enthusiasm and optimism of youth. I had fought a winning battle against the elements, and now I had only one or two miles walk to the shores of Loch Coruisk, which I could now dimly see far below me.

It was half-past-one when I left the tarn, striding quickly over the tufty grass, stumbling over boulders covered with phosphorescent lichen. Far away, to my half-left, a dim lump rose, stretching across the horizon from left to right. Was it cloud? Or mountain? According to my memory from the study of my map (which I had inadvertently lost whilst descending the screes above) they should be the Cuillins at the head of Loch Coruisk. A light flashed! I rubbed my bleary eyes in amazement. Surely, I was imagining it? But no. It flashed again. And again. A mountain distress signal? Someone hurt and signalling for help? I quickly galloped down the brae at the risk of a broken ankle, hoping to be of some help. It looked at least six miles distant, two hours' hurried walk. Then to the right, another light shone for a moment. Ah, someone was on the way to the rescue. But I still hurried, in case I would be of any use. Loch Coruisk was near now, perhaps quarter of a mile. It was quarter past two and still very dark. As I rounded a hillock, a number of white squares came into view below me, at the edge of the Loch. Were they boulders, or white-washed houses? A decrease in the intervening distance showed them to be houses. As I was not at all sure of my bearings, I resolved to go to one of the houses and risk the occupants' wrath by asking the way to Sligachan. The lights could wait five minutes. They were flashing regularly, and I was sure that the distance between them had diminished.

Now, about 50 yards from the shapes, I realised that they were tents and not houses – obviously it was a small camp near the head of Loch Coruisk. I wearily clambered over a wire fence and squelched over to the nearest tent. About 5 steps from it dismay flashed through my brain and I dizzily sat down in a whirling confusion – for the tent before me as I gasped was the one I had left over six hours before: Margaret's. I laughed weakly and realised my folly. I had descended the wrong side of the ridge, and this stretch of water beside me was Loch Brittle, not Loch Coruisk, which was ten miles away. The lights I had beheld flashing were lighthouses far out to sea marking the 'Cocktail Islands'.

'Margaret' I called quietly. 'Mm? What? Who's that?' 'Alan.' A violent upheaval took place inside the tent and her head appeared through the doorway. 'What's the matter?' 'I must have come down off the wrong side of the ridge' I confessed. 'Come on in, I'll get some tea brewed' she offered. Thankfully I took my sopping boots and socks off, pulled my pulpy anorak over my head and crawled inside. Soon the stove was purring, and my clothes steamed wildly. A large candle and an electric lamp lit the small tent, revealing what a woefully dismal sight I presented to the world in sundry. My hair was soaked and hung in tangled hanks over my head, dripping everywhere. My trousers were imbibed (sic) with gritty sand and torn badly around the ankles. However, a good hot cup of tea worked wonders and, when followed by hot buttered toast and beans, I once more began to take an interest in the world. Four-o-clock was the latest I could start off, for I intended to return the way we had come, up Glen Brittle, over the col and down into Sligachan. It was 3:15 so I pillowed my head on my rucksack and attempted to get a little sleep before my return. But no, the strong wind would not allow that, for, increasing in fury, it twice wrenched some guys from the sandy soil, causing the thin canvas to flap wildly, so out I crawled again and got wet once more.

A dim light filtered through the stormy sky, revealing a grey and black landscape, frightening in its sombreness. Stormy Petrels swooped above forcing strangled shrieks from their hoarse throats. They were the only other living things visible on the tempest-tossed scene. Shuddering violently, I pulled on my wet anorak, forced my complaining feet into my boots, shouldered my rucksack and bade goodbye to Margaret, having promised to keep moving quickly to keep warm. Enough light was present to show my way clearly as I struck the rough road, which led me past the small hamlet and up Glen Brittle. I remember faltering for a moment as I realised I had left my precious camera in Margaret's tent but could not muster up enough will power to return and fetch it. I could fetch it from her house in Manchester, I reasoned. Tired I was, but not so much as to stop me tramping briskly along to keep a vestige of warmth in my chattering body. Drizzle penetrated everywhere, and, when I struck off the road after an hour's rapid walking, I sunk two or three inches into the miry earth with each soggy step. My path was well-marked, and I had no difficulty in finding my way over the col, across the top, and down past the flood-swollen torrent to Sligachan. Despite my necessary haste, it took me three-and-a half hours before I thankfully dripped into the Sligachan Inn to pick up my surplus kit that I had dumped there the previous afternoon.

The porter eyed me dispassionately; he was used to English climbers and their queer ideas of pleasure. Still, he soon had a good fire in the lounge for me, where I attempted to evaporate my shivers before the bus came at quarter-past-eight. Not much had been accomplished before the ancient vehicle rolled up, so once more I heaved myself

(Note: February 2018, 65 years later: My hand-written school essay ends abruptly at this point; the original notebook has pages missing. The account is almost at an end, so I have taken the liberty of finishing it as though I had written it at the time. My memory still holds good.)

…aboard. The vehicle was full of passengers from Portree and my return ticket, boldly marked 'Return' was accepted with a cursory glance. The widows were steamed up concealing the passing views and I slept deeply, to be awoken by the bustle of departing folk. The bus emptied, and I realised I must be at the terminus in Armadale. I alighted and stood bemused, gazing around trying to identify my surroundings but failing. 'This is Armadale?' I said to a person standing by.

'Ach noo' he declared. 'This is Kyleakin'. I stood flabbergasted. Kyleakin was a very long way from Mallaig, I remembered. 'How do I get to Mallaig?' I queried plaintively. 'Ye'll have ta catch yon ferry to Kyle of Lochalsh on the mainland, 'he responded,' and then catch the big MacBraynes boot doon the Sound of Sleat'. My mind whirled. 'But I've got hardly any money.' In fact I remember I had the 2d for the short shuttle ferry to Kyle, then very hazy memories of approaching an official on the huge boat that was, fortuitously, almost ready to depart. I explained my predicament and the kind-hearted fellow assessed me, took me under his wing and shepherded me below decks to a bustling galley which was blissfully warm, laced with mighty incandescent water pipes. I was fed a massive bowl of hot thick pea soup, allowed to undress to my pants and strew my garments around and then curled up in a snug corner and slept the sleep of exhaustion. I couldn't tell you how long the voyage took, but I was awoken when we arrived and donned my now-crisp clothes, thanked all those concerned profusely, and strode ashore to find my bike, stored behind a nearby office, and commence my 500-mile ride home. I vowed to be back.

February 2018

Now you could be forgiven for suspecting that all this was the product of a young, highly-imaginative mind. Not so. Round about ten years ago I chanced on an encounter with a couple of guys from the Karabiner Club, a climbing group based in Manchester. Faint memory bells jangled. 'Do you happen to have heard of a lady who used to be a member in …1950's? Margaret Piggott?' 'Certainly' answered one of them, who was getting on in years. 'I was speaking to her yesterday. She lives in Haines Junction in Alaska.' (Anne and I had been in that town a year or two before; but that's another tale.) Suffice to say we got in touch with her and she promised to contact us when she was next in the UK. Time passed. A few years later came a knock at the front door. 'Alan Heason?' 'Yes?' 'Margaret Piggott.'

Well, she was now a grizzled mountaineer, backcountry guide, and apparently author of many expedition guides to the wild area where she now lived. It would be untrue to say that it was a meeting of souls. She was hard-bitten in the extreme and we had little in common to discuss. Civil enough, but not a meeting of minds. We talked desultorily for about 30 minutes and she left, but not before confirming, in remarkable detail, my memory of our brief encounter, exactly as recounted above, back in 1954. Perhaps she rather spoilt things by recalling that she remembered me as a rather over-confident, somewhat gauche and inexperienced youth, which just goes to show that her memory can't be all that accurate. Can it? Moi? Gauche? Inexperienced? Mais non! Although, come to think of it, it had been my first experience of 'proper' mountains.

I'd read all the books, though…

Comments

Bravo Alan. That was lovely to read.

Great story I really enjoyed it. Interesting to think that if you arrive in Mallaig this day having never been to the Cuillin, or Skye, without a guidebook or internet, you would probably have a similar experience.

Brilliant. There's something about Skye that makes it forge the strongest memories.

Brilliant article. Very talented writing.

Indeed. Remarkable for a 16-year-old.

Mick