As we mark 70 years since the first ascent of Everest on 29 May 1953, the world's highest mountain has just made its debut in the Metaverse with Sandbox game 3VEREST. Adam Butterworth looks at where the game fits in the long history of Everest-themed entertainment.

In 1955, just two years after the first ascent of Everest by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, the Mt.Everest board game invited children aged 8-12 to "Climb the World's Highest Mountain" using magnetised mountaineer figurines to ascend a pyramidal representation of Everest.

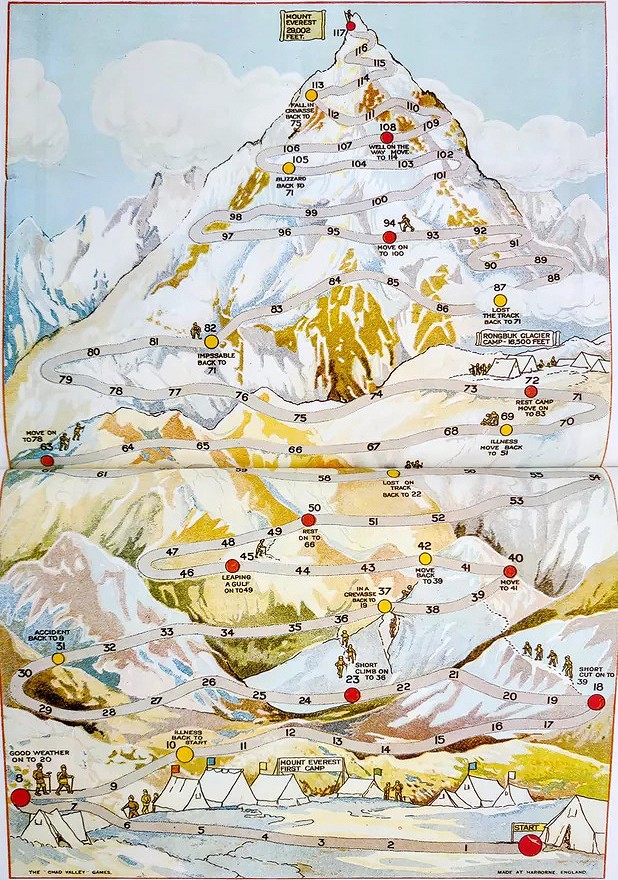

This was not the first game to have taken inspiration from Everest, nor would it be the last. A 1923 game, similarly named Mt. Everest, allowed between 2 and 6 players, divided into teams, to attempt to send two climbers to the summit. At the time of its release, the first two Everest expeditions had only just taken place. Yet the game marked out the Rongbuk Glacier, which the 1921 expedition had identified as being the key to accessing the mountain, as a crucial waypoint. Before it had even been climbed, the fascination with Everest and the desire to bring a facsimile of the Everest experience to the public was already strong.

In 1975, game manufacturer Capri, which had several sport-focused board games in its collection, added greater complexity to 1955's Mt. Everest with Conquer Everest. Again, players ascended a 3D model of Everest, but this time were aided or prevented from progressing by their ability to accrue team members and equipment.

At a basic level, all of these games are essentially themed versions of Snakes and Ladders, where progress or retreat are determined by climbing-themed fortunes and mishaps — the discovery of a faster route, fair weather, the onset of storms or a Sherpa developing snow blindness. But there are more complex climbing board games. 1976's Assault on Mount Everest allowed players to assemble a team from the members of the '53 expedition and included a note from the manufacturers warning players that the game may feel like "Chinese water torture at times". It also reassured them that they could always write to the designers if they were really struggling.

In my own home, tucked away in a cupboard upstairs, is a copy of 2013's Mount Everest – a Christmas gift from a board game-obsessed friend. This take on Everest-as-board-game reflects a more modern understanding of the mountain. Players are put in the role of mountain guides who must attempt to safely lead their inexperienced clients safely to the summit and back to Base Camp.

A Broad Peak expansion pack is also available, reflecting the real-world incentives of guided clients who want to "collect" multiple eight-thousanders and speaking to the "gamification" of high-altitude mountaineering, where Sherpa assistance, fixed lines and bottled oxygen have become trump cards for summit success.

Since 1953, Everest (8,849m) has been climbed around 11,000 times by over 6,000 people. Over 320 deaths have occurred since 1922.

Tales of triumph and tragedy on the world's highest mountain have inspired game designers. And the trend is not restricted to board games. Everest has also been the mountain of choice for numerous video games and, in particular, virtual reality games including Everest VR.

There is a discernable pattern at play; with each advance in entertainment technology, a desire arises to make an accompanying mountaineering product, often with Everest as the focus. Readers will perhaps remember the 1998 film Everest, which took advantage of burgeoning IMAX technology to film an attempt on the mountain by climbers including Jamling Tenzing Norgay. Everest was not the only location to receive this treatment, with Antarctica, the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean and the Earth's orbit also being the subject of big IMAX projects.

As themes for entertainment go, the obvious extreme of the world's highest mountain makes it a natural choice and the more immersive works based on Everest trade on the idea of recreating the real-life experience of climbing the mountain. Even 1976's labyrinthine Assault on Mount Everest advertised itself as being a "simulation" of the ascent.

So what of the very latest technologies? This month, to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the first ascent of Everest, a new game, 3VEREST was launched on The Sandbox gaming platform. Both the platform and the game are inspired by the ideas behind what is commonly referred to as "Web3" – the concept that the Internet can be run in a decentralised form using blockchain technologies and tokens like NFTs.

The game is the brainchild of Gillian de Brondeau. De Brondeau works for a Crypto company based in Singapore, so it's clear he has a personal investment in Web3. He's also a mountaineer, with ascents of peaks including Mont Blanc to his name. Part of his inspiration for creating the game, he says, was a desire to give people like himself, people who are unlikely to ever climb Everest or even visit Base Camp, a taste of that experience.

However, he's also keen to stress that the game is not a one-to-one comparison. 3VEREST, which has been built for De Brondeau by Smobler Studios, has a style similar to that of the popular game Minecraft, with a world constructed from individual blocks that give it a distinct, cubist appearance.

Unlike some of the other properties based around Everest, recreating a completely analogous experience is not the main focus. While the game uses features of the mountain like Base Camp and the Khumbu Icefall, the gameplay in these areas can be very different from the real-world experience on Everest. In Base Camp, players can interact with each other much like they would as climbers at the real Base Camp. They can also learn about the mountain and the Sherpa people in informative packages, as visitors to the mountain might absorb the culture during their visit. But when they leave Base Camp, the experience becomes much more that of a platform game – as players dodge obstacles and ascend features in the Icefall.

For this first phase of the game's release, activity extends only as far as Camp 2, where players can seek out a yeti and interact with other non-player characters. Like those who have made Everest-themed games before him, De Brondeau found that the geography of Everest and its regular camps lend themselves naturally to game design, providing challenges for players and checkpoints at which to pause gameplay.

3VEREST is testament to the mountain's persistent ubiquity in human culture. No sooner has an entertainment technology been invented than an Everest adaptation is in the works. By dint of its being the world's highest mountain, perhaps Everest was always destined for serial adaptation.

Mountaineering journalist Angela Benavides, who has covered the mountain for several years, thinks that Everest itself has always been a "a source of interest for all kinds of audiences" since Mallory and Irvine's fateful expedition in 1924— when the pair went missing — and that this also gives it an "historic allure" which goes some way to explaining the wider world's continued fascination with it.

Angela follows the social media feeds of those who set out to reach its summit and she has the impression that Everest social media has itself become a form of entertainment, in ways both positive and negative. She hypothesises that people choose to follow would-be summiteers with whom they identify, whether on grounds of nationality, race, gender, disability or any of a host of other factors. They draw inspiration from the success of someone like them or someone who they see as having overcome additional challenges. But there are also those who follow these stories in search of schadenfreude.

"As in many other aspects of life, some individuals use social media to prove themselves right," says Benavides. "Big mountains and the drama that sometimes unfolds there provides a suitable field to set moral standards, and express opinion about what should be or not." There's also a sense of the social media audience picking teams, their own heroes and villains. Those they approve of and those they don't.

During this Everest season, Nimsdai Purja shared footage of a rescue which took place at the mountain's south summit.

Social media has brought the Everest experience closer to us than ever before and allowed those with an interest to watch people attempting the mountain in near real-time. Viewers can follow the progress bars of climbers' inReach devices and watch the scoreboard tick over as record-chasers rack up multiple 8,000ers in faster and faster times. They can cheer for their heroes and denigrate those whose tactics they disapprove of.

Footage from the mountain, relayed faster than ever before, allows social media followers to access the Everest experience in a more visceral form than any other entertainment has so far provided, creating a quasi-spectator sport. The logical end-point perhaps of 'Everest as entertainment' is that the mountain itself becomes the playing field.

Adam Butterworth is a climber based in south Wales and the Assistant Editor of the Alpine Journal.

Comments

"The game is the brainchild of Gillian de Brondeau. De Brondeau works for a Crypto company based in Singapore, so it's clear he has a personal investment in Web3."

NFTs? Web3? Works for a Crypto company? Checks out all the 'shill' marks. Is the game 'the highest ever pyramid scheme' then?

Somehow, that wasn't really on my 'UKC 2023 articles' bingo card...

If anybody still needs explaining what the whole "Web3" fraud really is (hint: indeed a fraud), here is a great website documenting all the latest Web3 swindles and faults:

https://web3isgoinggreat.com/

Adam Butterworth as in THE Adam Butterworth? Power to the pucc 💪

Well, that sounds like total shite.

I thought this was a good article: https://stackdiary.com/web3-scam/

Unlike Alex0989, I am not a bot 😁

But I am traditionally sceptical, so there's probably an element of confirmation bias in me liking that article.