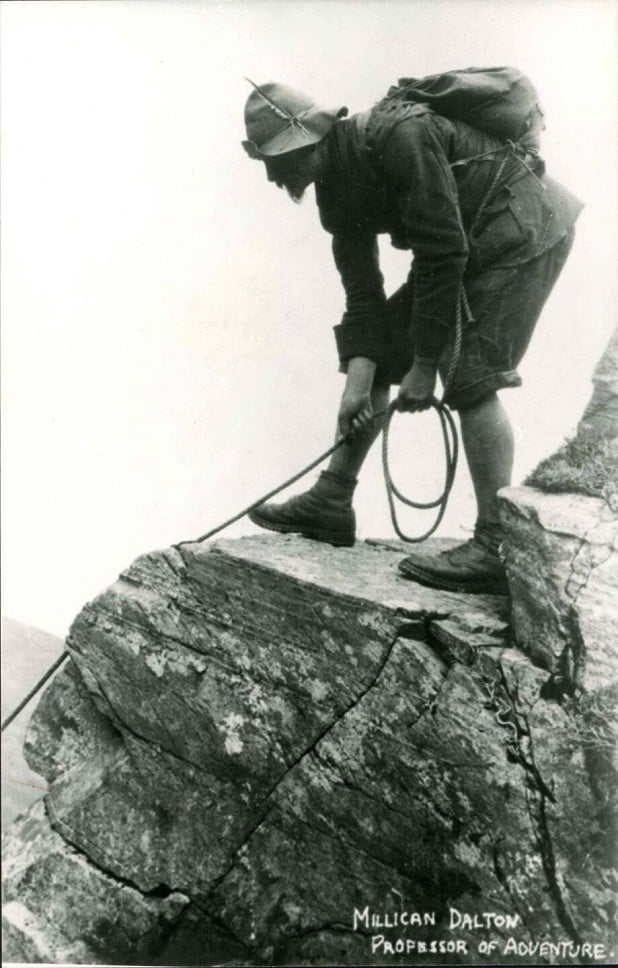

Iona Glen tells the story of Millican Dalton (1867-1947), a self-styled 'Professor of Adventure' who lived in a cave in Borrowdale and led camping and climbing trips in the vicinity of Keswick. Photos by kind permission of the Fell and Rock Climbing Club.

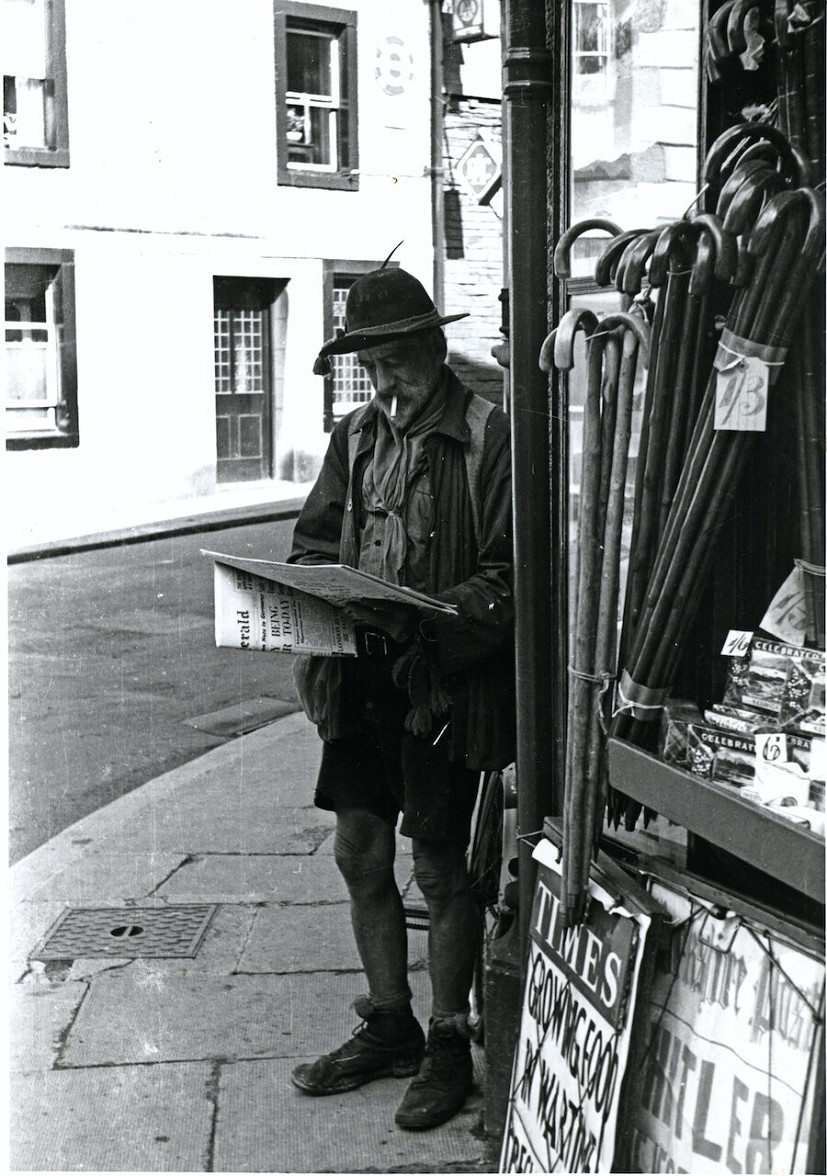

In a disused quarry cave beneath Castle Crag during the first half of the twentieth century lives a man known to locals as 'the Caveman' or the 'Hermit of Borrowdale', happy to be termed Robinson Crusoe, Rob Roy or Robin Hood, and styling himself the 'Professor of Adventure'. He cuts a striking figure: bright blue eyes and shaggy hair, tall and lean with knobbly knees emerging from army puttees and hobnailed boots (no socks). His unhemmed clothing is all hand-made, sewn from discarded materials like canvas and old waterproofs, with a tartan shawl that can be used as a blanket or sail at need. A pheasant's feather decorates his signature Tyrolean hat; occasionally he adds a sprig of heather or uses a red bike reflector to keep the brim in place.

When friends and visitors hike to see him at his jokingly named 'Cave Hotel', a beckoning curl of smoke indicates that the caveman is in residence. The camp consists of an open fire, a sewing machine, ingenious riggings for suspending kitchen implements and storing books and papers, and a bed of dry bracken with an eiderdown quilt.

At other times, he can be spotted in Rosthwaite, Grange in Borrowdale or Keswick picking up supplies with his trusty bicycle, particularly his favourite Woodbine cigarettes and copious amounts of coffee. These substances are his two indulgences; otherwise, he is teetotal and vegetarian, living mainly off nuts, foraged berries, and his own recipe of nutritious wholemeal bread. Spending his days climbing and exploring in the Lake District, the 'Professor of Adventure' offers his services as a mountain guide and equipment supplier to mixed-sex camping expeditions, for novices and experienced climbers alike.

***

Millican Dalton was born in 1867 and spent his early years in Nenthead near Alston, one of the first purpose-built industrial villages. His family relocated to south-east England some years after his Quaker father's early death, settling in north London and then Chingford, Essex. As an adult, Dalton went to work as an insurance clerk for the Union Assurance Society (Fire and Life) in London. His dissatisfaction with this job is the inciting incident for Dalton's future living arrangements and subsequent mythology.

In 1904, he left this job and decided to pursue an outdoor life close to the natural world. A Sunday Chronicle correspondent in 1933 was told: 'Day after day I went to the office at the same time. But this was not the life for me. I gave up my job in the commercial world and set out to seek romance and freedom.' This turning point encapsulates the great appeal of Dalton's story. Many people, then and now, fantasise about escaping the stifling conventions of a bureaucratic job, yet few have the commitment or opportunity to pursue this dream.

In the summer he set up camp near Keswick, pitching his tent at High Lodore for many years before moving to the Cave Hotel. During the colder months, he lived in various parts of the south-east, first on a plot of land in Thornwood, Essex while he was still employed as a clerk, then on the edge of Epping Forest, and lastly in Marlow Bottom valley in Buckinghamshire. Prepared by a childhood of camping and experimenting with designing lightweight equipment with his brother Henry, Dalton set himself up as a mountain guide and supplier, leading itineraries in the Lake District, Scotland, and Europe. Cumberland and Westmoreland (now Cumbria) had been popular resorts since the Romantic era.

'Mountaineering', a term first recorded by Coleridge in 1802, grew in popularity and accessibility over the course of the nineteenth century. Climbing clubs sprang up, including the London-based Alpine Club (1857), the Climbers' Club (1898), which Dalton joined in 1902, and the Fell and Rock Climbing Club (1906-7), of which Dalton was also a member. Women's associations were also formed, such as the Scottish Ladies Climbing Club (1908) and the Pinnacle Club (1921).

In this context, Dalton was well-placed to make a living from his climbing and campcraft expertise. He was not shy of publicity, posing for promotional photographs and even lending his distinctive image to an advertisement for 'the Keswick boot'. In the 1913 issue of the Fell and Rock Climbing Club's journal, he contributed 'A Camping Holiday', an account of one of his expeditions doubling as a not-so-subtle advertisement:

One of my favourite camps is a steep fellside in Borrowdale, commanding a perfect view of a perfect lake, Derwentwater, framed by mountains on each side, with the purple bulk of Skiddaw in the distance; and I have watched many gorgeous sunsets from that spot, as we cooked over our wood fire and dined in the open.

Dalton describes an idyllic experience involving a midnight row to Derwentwater and an impromptu island campfire with oatcakes and hot chocolate. Other adventures involved ghyll-scrambling or lashing tree trunks together to make rafts.

Many biographical accounts of Millican Dalton adopt a tone of wide-eyed hero worship, and the language of derring-do and great scrapes reminiscent of classic children's literature and adventure tales. His words lend themselves to pithy quotation, such as 'Use is everything' or the words inscribed in the Cave Hotel: 'Don't waste words. Jump to conclusions.' The fragmentary quality of the sources for Dalton's life also creates a folkloric mystique, consisting of oral testimony, a few press cuttings, a couple of articles, and a lost British Paramount news feature from 1941. Many photographs, letters and papers were lost when his Epping Forest hut caught fire, while his memoir A Philosophy of Life went missing from his hospital bedside at his death in 1946.

Yet to mythologise Dalton purely as a maverick, another role model to be filed under the ahistorical index of loveable British eccentric, ignores how his ideals were rooted in a widespread existing culture. Many people sought a return to greater self-sufficiency and proximity to nature in opposition to urban industrialised society. Instead of being simply 'ahead of their time', interesting and non-conforming individuals like Dalton complicate stereotypical understandings of what that time really was.

When Dalton was born the Arts and Crafts movement had already begun, disillusioned with the mass production of mechanised industries, advocating for the importance of simplified living, hand craftsmanship, and the dignity of workers. From the 1880s, the 'pastoral impulse' identified by historian Jan Marsh cemented an idealised view of pre-industrial British society and rural life. This inspired numerous attempts to 'get back to nature' at the turn of the century, from wealthy Fabian Society socialists and artists like Rupert Brooke or the Bloomsbury Group, to working-class members of Ramblers' clubs and associations campaigning for public footpaths and rights of way.

Dalton's appearance, vocabulary, and style of camping bears similarities to the immensely popular Boy Scout and Girl Guide movement (founded 1908 and 1910 respectively). Indeed, Dalton maintained that it was he and not Lord Baden Powell who had invented shorts, although in fact both men may lay claim only to have popularised their use in Britain.

His pacifist and left-wing political views, however, align more closely with the various splinter groups that became disillusioned with the Scouts' militarism and conservatism, especially following the traumatic impact of The Great War. These included groups like the Woodcraft Folk, still in existence, and The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift ('proof of strength' in archaic Cheshire dialect), whose 'kinsmen' would camp and perform exercises wearing surcoats and occult heraldic badges reminiscent of a crossover between the Bauhaus and a medieval re-enactment society. For many, camping was a form of experimental living that cultivated the good health and values of self-reliance and community that 'decadent' modernity had lost.

These sentiments must have expanded Dalton's potential mountaineering clientele and are present in his own writing and newspaper interviews. In 'A Camping Holiday', he extolled the benefits of an outdoors life:

Camping provides the completest possible change from ordinary civilised town existence; and being the healthiest kind of life, as well as the most unconventional, is the best antidote to the rush and stress of city work … the open-air life has been found by experience to be a cure, not a cause of rheumatism, as it is likewise for consumption and neurasthenia.'

Of course, Dalton is remarkable for the degree to which he was committed to these ideals, a complete lifestyle rather than periodic relief, forsaking bricks and mortar for a home of rock or tent canvas. He is also a useful example for posing questions around the inequalities of access for this way of living. What space was there, and what space yet remains, for like-minded folk lacking the respect, and trust in their own safety, conferred by Dalton's gender and class? It is not insignificant that he was described by one of his obituaries as 'a true gentleman of the hills' (my emphasis).

In Epping Forest, Dalton made discretionary arrangements with its Forest Keepers enabling him to keep setting fires there, in a similar way to how affluent walkers could afford to tip gamekeepers while walking across private land. Gypsies, travellers and 'vagabonds' who also tried to live in the Forest's environs were not so fortunate. In Cumbria, Dalton's only disturbance seems to have come during World War Two, when Keswick's fire warden noticed the light from his campfire and paid an admonishing visit. These are issues still pertinent today: what kind of person is afforded the privilege of being an unhindered eccentric rather than a vagrant or general nuisance?

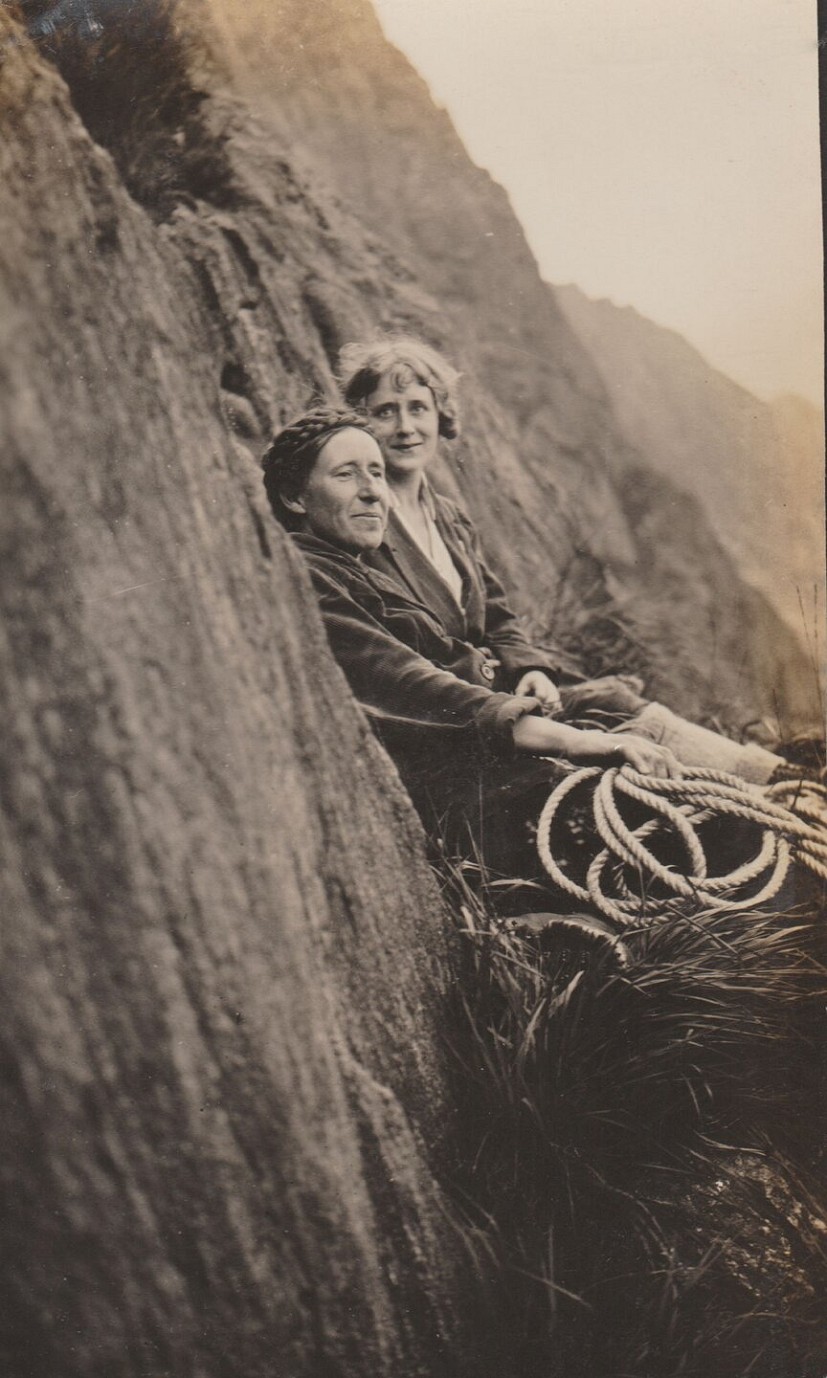

Nevertheless, Dalton was clearly passionate about extending access to mountaineering and rock-climbing. His merits as a climbing instructor were vouched for by geologist, geographer, and teacher Mabel Barker, the first recorded woman to ascend the Central Buttress of Scafell in 1925, in her affectionate obituary of 1947 entitled 'Memories of My First Leader':

He really taught his initiates, explaining and showing the use of belays, knots (I was never really happy in the use of any knots but his), the safe length of a pitch, care for the leader, and the general safety of the whole party. Probably by modern methods, he was over-cautious, but it's a good fault.

The two had first met in 1913 when Dalton provided tents for her group of schoolgirls camping in Seathwaite and stopped by their camp to suggest some climbing. From that point, Dalton encouraged Barker's pursuits, leading her and a friend 'by glimmering and guttering candles through Dove's Nest Caves' a year later, and joining a group expedition she organised to the Austrian alps in 1922.

At the age of seventy-five, Dalton retired, but he kept climbing into his eightieth year. Many of the early mountaineering clubs had focused on pioneering and recording first ascents. Dalton could play this sport, writing about new routes he traversed around Keswick for the Fell and Rock Climbing Club Journal. Yet he was not particularly concerned with 'conquering' new summits; Barker claimed that he had 'no ambition to be among the great climbers. In a way he had no ambition at all.'

Dalton revisited the same places, focusing on deep knowledge and experience. In this respect he is akin to Aberdonian contemporary Nan Shepherd who wrote about her lifelong relationship with the Cairngorms in The Living Mountain. Her delight in climbing 'merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend' dovetails with Dalton's words to the Daily Mirror in 1941: 'You can't feel lonely with nature as your companion.'

Dalton's favourite Cumbrian climb was Napes Needles, near to Great Gable. In celebration of his fiftieth ascent there, he carried kindling with him to brew fresh coffee, which he enjoyed with a cigarette. After that, he repeated the trip on the same day each year. We might imagine him up there still, not only a mountain-climber but a mountain-dweller, demonstrating the enduring fascination of the fells, and the entwinement of the human and natural world. The Cave Hotel still awaits.

Comments

Absolutely loved this. Many thanks to Iona Glen for researching and writing it and to Natalie for getting it on here for us all to read.

Have always been fascinated by Millican Dalton. The title, the Professor of Adventure just says it all!

Mick

Excellent, really enjoyed that. Minor point: Boy Scouts founded in 1907 not 1908.

That belay he has looks well dodgy by modern standards. It's one down, all down! And Mabel Baker was some character, and her ascent of CB really groundbreaking for its day.

Thanks for posting.

Cracking read. Have really enjoyed the longer profiles and historical pieces here of late.

Matthew Entwistle‘s biography on Dalton is worth a read. Based on this, I don’t agree with the article's “inequality of access” spin. He was a lowly insurance clerk not a knight of the realm! Entwistle says the details of Dalton's friendship with the Epping Forest Keepers are uncertain. Dalton was though "charismatic and instantly likeable", which probably went a long way with his dealings in life.

It seems as though he rented the land for his camp above High Lodore Farm. The landowner of Castle Crag donated it to the NT in memory of his son and men of Borrowdale killed in WW1, so they may well have been of the benevolent type, and tuned a blind eye to the cave activities of the novelty/celebrity Dalton.

Incidentally it looks as though he didn’t quite get to climb in his eightieth year, he died early in 1947 aged 79.