Do the mountains, and our relationships with them, remain stable through time? Author, Matthew Shipton, surveys the continuations and fractures whilst considering a new biography of John Tyndall by Roland Jackson...

As one ancient tale goes, the very first city in Greece was established at the foot of a mountain in the Peloponnese. The second-century geographer Pausanius recounts the story that King Lycaon chose the site of the first great city of mortals at the foot of Mount Lycaeus (Wolf Mountain) whilst also establishing the first series of sporting games just below the summit. For good measure, an altar to Zeus was built to crown the mountaintop and it was said any who entered the holy precinct would die within a year. In this mythological foundation story, urban life was created in balance with its mountain antithesis; the natural arena of physical challenge forever under the shadow of death from the immortal presence above.

Regardless of the truth of this tale (and there is some archaeological evidence in support of parts), it seems the link between urban life and outdoor activity for its own sake, rather than for some utilitarian purpose, has a long history. Today there appears unparalleled interest in outdoor activities, not least those relating to mountain pursuits, whilst urbanisation is at its greatest extent in the history of humankind. The outdoors is often presented as a location in which to restore oneself, to seek wellbeing and mental equilibrium – a counterbalance to the pressures of fast-paced, complex urban life. In the midst of what looks like a mental health crisis, the values we place on our relationship with the natural world might seem very modern. Yet we do not have to travel as far back in time as King Lycaon to see that current relationships with mountains are not without earlier precedent.

In a new biography of the Victorian scientist and mountaineer, John Tyndall, we find a figure through whom we can trace some early parallels to the way in which we currently engage with mountains. In his mid-twenties, Tyndall made his first visit to the Alps. Following what was already a well-established trail through the Bernese Oberland, from Grindelwald to Kleine Scheidegg and down into the Lauterbrunnen valley. But he was unmoved by the great wall of the Eiger, Monch and Jungfrau. On his way back to Basle he paused to gaze back, reflecting: "this is the last I saw, or perhaps will see, of the Swiss mountains." Back in England, Tyndall was a rising star in an age of science febrile with innovation. He counted amongst his social firmament the scientists Huxley, Darwin, Faraday; writers as esteemed (and controversial) as Thomas Carlyle, and he was particularly drawn to Tennyson, who was shortly to be appointed Poet Laureate.

Tyndall, too, was to become a central figure in the scientific establishment. But he was also an outsider, having grown up and been educated in provincial Ireland unlike many of his contemporaries in Victorian Britain. And as with the principals of the age, he held the characteristics of self-reliance and a rugged determination in highest esteem, embodying them in his life's work. This background, in part, fuelled a burning ambition to ascend his social rank and drove Tyndall ferociously towards a series of fine scientific achievements. But for all this drive and energy, he was afflicted by physical and mental ailments from relatively early in his career, his illnesses exacerbated by severely heavy workloads.

A decade after his first visit, Tyndall planned another trip to Switzerland in order to carry out research on the movement of glaciers. But, quite unexpectedly, Tyndall's second experience of the Alps proved transformational, and not solely in relation to his scientific endeavours. The biography's author, Roland Jackson explains, "Tyndall lived in a time when the Alps were part of the cultural landscape, through tourism and the wide artistic interest in the concept of the sublime." But it appears some deeper and more personal shift in Tyndall was caused by the mountains: "what changed was a sudden, direct personal engagement with the landscape. Not just physical but also, in a way, spiritual." Tyndall had spent much time outdoors, not least during his early career as a surveyor, but had relied on other remedies to improve his wellbeing, "Mr Bass has proved my apothecary", he once wrote in his journal. This remedy, not unknown in modern climbing circles, perhaps required augmentation from a purer source.

In short order, Tyndall made an impressive, if spontaneous, unguided climb of the Mer de Glace to the Col de Géant and later ascended Mont Blanc with the minimum number of guides he thought possible. He was no longer simply Tyndall the scientist but also Tyndall the mountaineer. This transcendental relationship is one we're still trying to understand and explain. Through exploration of Tyndall's life, we can recognise commonalities in the motivations that have led people to answer the 'siren song of the summit', to use Robert Macfarlane's mountain poetics. As a friend said of Tyndall, after a frightening ascent of the Slieve League in Ireland, "This necessity for strong stimulus in the shape of present danger is quite characteristic of Tyndall".

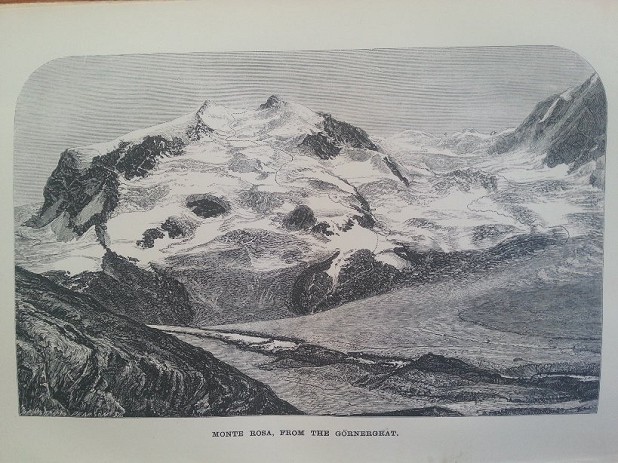

In all aspects of his life, Tyndall was keen to forge his own destiny. As a scientist, he valued experimental over theoretical science, as a mountaineer he was drawn to unclimbed routes and, quite remarkably, solo climbing. He knew the risks of venturing alone onto a glacier, but the draw proved irresistible. "You cannot contract a closer relationship with the landscape than through a solo traverse of a glacier"; "the feeling of self-reliance is inexpressibly sweet." This daring approach led to one of his finest achievements, and one that would today still raise questions as to the risk involved – the first solo ascent of Monte Rosa in 1858. Tyndall's report of the climb was sent to the Times newspaper by his friend, Faraday, and stated pithily: "I strapped half a bottle of tea and a ham sandwich on my back, left my coat and neckcloth behind me, and in my shirt-sleeves climbed to the top of Monte Rosa alone." When he did seek assistance in his climbs, he was parsimonious to the extreme. For a successful ascent of the Aletschorn in the Bernese Oberland he was assisted by a single guide, which was remarkable for the period and resulted in Tyndall's reflection: "We live in the sky, not under it", a phrase that deserves a wider audience but perhaps wouldn't have been inspired on a mountain top surrounded by a crowd.

Tyndall was not the only mountaineer to value or seek out solo adventures. A friend and sometimes companion in the Alps, the Reverend A.G. Girdlestone, could be considered the first to legitimise solo and guideless climbing in the Alps. His work on the subject, The High Alps without Guides of 1870, still reads true today in many aspects of solo climbing. The highlight of the work is the final chapter on planning for guideless climbing and remains a useful guide - though the case for carrying wine, brandy and raw eggs hasn't quite traversed the intervening periods so successfully.

In the character and approach of Tyndall (and Girdlestone) there is something recognisably modern. But Tyndall's character is not always straightforward - the complexity of his psychology is almost always on display. On summitting the Weisshorn, the impressive first ascent of 1861, he wrote about the ultimate value of being in the moment, a kind of mindfulness avant la lettre, whereas in a later journal entry he reflected: "mere beauty, mere grandeur, the enchantment of emotion—are not sufficient to fill a human life. Intellectual occupation must be added." This eccentricity is displayed in his attitude to literature as well. He found some writing very difficult, saying: 'to forget oneself and be simple is the highest quality of a scientific writer.' And yet was quite critical of others, such as Whymper, whom he accused of introducing a new and unpleasant direction in mountain literature.

But this remark speaks to another underlying pathology in Tyndall, pugnaciousness when faced with criticism he thought unfair. "This remark is more to do with the negative presentation of Tyndall by Whymper in Scrambles in the Alps" believes Jackson. Not only had the two had come into conflict over first attempts at the Matterhorn, where Whymper had surpassed Tyndall's earlier efforts and achieved the first ascent in 1865, but they were also competitors in an astonishingly rich period for mountain literature. 1871 saw the publication not just of Whymper's work, but also Tyndall's Hours of Exercise in the Alps and Leslie Stephens' The Playground of Europe.

As a portrait, Jackson offers a view of Tyndall the mountaineer as driven, competitive, by turns contemplative or combative. His views on society and politics, however, are harder to accept in the round. Jackson says of Tyndall, "I think today he would seem quite boorish. His views, while shared by many (though not all) at the time, would be quite offensive." His views on race, most notably displayed through his attitude to the Morant Bay rebellion in Jamaica of 1865, a case in point. But like him or not, the way in which he interacted with mountains still speaks to our contemporary age. In order to escape from the burden of work and rigid expectations within society, to find inspiration or solitude, physical challenges against which to test himself, a sense of exploration or experimentations – all these desires were sated by mountaineering.

Moreover, mountaineering eventually permeated his whole way of thinking. When working on a visual spectrum of radiant heat he described the results on a graph as appearing like the Matterhorn, and took a great interest in a young woman who he first saw gazing at a picture of the same mountain. At that time, he had yet to succeed in climbing the mountain and it clearly weighed on his mind (he would later achieve the mountain's first traverse, driven, no doubt, by a sense of competition with Whymper).

The mountaineering landscape of literature, endeavour and history is paradoxically ever-present and ever in flux and Jackson's biography offers the modern reader a view of the shifts between periods, as well as the continuities. The words of Tyndall's great idol Tennyson from Canto 123 of In Memoriam A.H.H. on the power of geology prove germane. As a poetic rendition of the forces of orogeny (from the ancient Greek for mountain, 'oros') and the epeirogenic (from Greek epeiros, 'land' and genesis, 'birth'), the flow relationships with mountains through the ages is a song from the pinnacle:

"The hills are shadows, and they flow

From form to form, and nothing stands;

They melt like mist, the solid lands,

Like clouds they shape themselves and go."

Roland Jackson's The Ascent of John Tyndall: Victorian Scientist, Mountaineer, and Public Intellectual is published by Oxford University Press and available now.

Comments