This article, covering the basics of any first aid incident or 'DR ABC', is the first in the series:

1. The basics of any first aid incident or 'DR ABC'

2. Hypothermia and cold injuries (yes! In Scotland)

3. Avalanche survival

4. Leg fractures

The key to Scottish winter survival depends on preparation and the kit you carry. The key to surviving when things go very wrong, and you are now having to deal with a casualty or potential casualty, is tighter preparation and adequate emergency kit.

Before we get stuck into Winter First Aid, I'd like to share with you what a recent research study for sportScotland (1996-2005) highlights as the most common incidents, and human factors leading up to them, on the Scottish hills. The database describes 2446 incidents involving 3315 casualties. It is the most comprehensive survey of Scottish mountain incidents undertaken and the most exhaustive carried out in the UK.

Causes of Incidents

1. Navigation is the most commonly cited cause of all incidents (23%), closely followed by bad planning (18%) and inadequate equipment (11%).

2. Navigating off a plateau.

3. Experienced people are less likely to make navigation and planning errors, but 48% of incidents involving inadequate equipment are experienced people.

4. 11% of all incidents are caused through inadequate or missing equipment.

Casualty Details

1. Men are more at risk than women, possibly due to higher participation in activities which are inherently more risky, and possibly due to a greater tendency to take risks in any given situation.

2. The age group 21-30 appears to be a higher risk group.

3. Almost two-thirds of those involved in mountain accidents are considered to be "experienced". Eighty five percent of those involved in climbing incidents (rock climbing, snow/ice climbing and scrambling) are experienced.

Month of the Year

February and August show a relatively high number of accidents, possibly reflecting the number of participants at these times (to engage in winter mountaineering and summer hill walking).

Type of Activity

Hill walking results in almost three quarters of all mountain incidents and snow/ice climbing a further 12%.

Injuries

1. Limb injuries are the most common followed by fatal injuries, multiple injuries and medical problems.

2. Scrambling results in the highest proportion of fatal and multiple injuries.

3. Limb injuries are more common in hill walking casualties and spinal injuries are more common in rock climbing casualties.

Terrain

1. Over one fifth of all incidents take place on the open hillside where the terrain is generally mixed, uneven and unreliable.

2. Men are less likely to be involved in an incident on a footpath or on the open hillside or when the ground is wet but more likely to be involved when the terrain is rocky or covered in snow or ice.

Weather

1. The weather variable that accompanies more incidents than any other is wind.

2. In almost a quarter of all incidents there is no wind, rain, snow or cloud. Many incidents therefore take place when the weather is otherwise fine.

The basics of any first aid incident or 'DR ABC'

I am thinking of a typical day out: you and your mate going climbing in the Scottish Highlands. What follows is by no means an exclusive list of things that can go wrong, but it will hopefully help you start thinking about having the right kit and being prepared for when things go wrong. I am assuming a basic knowledge of first aid principles, including how to open and maintain an Airway (A), checking for Breathing (B) and controlling severe bleeding and Circulation (C). The first aid protocol DR ABC should be seen as a priority flow chart, where D (Danger) overrides R (Response), which overrides A (Airway), etc. However, if you've made it down to B (Breathing), yet the situation around you changes, like being in the middle of a loading snow slope, you go back up to D (Danger).

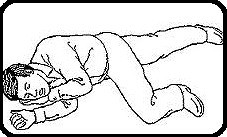

You find your mate at the bottom of a snowy slope. To begin with the situation wasn't dangerous for you to approach him (D). You shout his name and gently shake him, but he's unconscious (not Responding), which means you need to put him in the Safe Airway Position (see illustration), insulate him and get help. It begins to snow heavily. Snow sluffs are coming down around you. The slope above you could avalanche or a cornice could collapse above you whilst you're waiting for help to arrive. You need to move to a safe place (D).

Blue arrow scenario:

You've arrived at your friend, checked that the situation wasn't dangerous for you to approach him (D). He was talking to you coherently (R A B) at first but as you finish patching up a big bleeding wound (C) he loses consciousness (R). You need to put him in the Safe Airway Position, insulate him and get help.

Scenario: a slip down a snowy/icy slope

When faced with a first aid incident you must consider your own safety first and think: why has my friend slipped there? Is there an icy section where the crampons didn't bite, or did they fluff their footsteps? Why hasn't he/she been able to self-arrest? Can I get to them safely? In the standard first aid protocol this is what we call checking for Danger (D).

Stay on your feet and avoid having to use this ice axe technique

We're dealing here with Danger to yourself first and foremost and further danger to your friend and yourself, as in in an avalanched slope. It's easy enough in summer to establish whether, say, further rock fall will happen and decide if moving the casualty is appropriate or not. Winter terrain is ever changing: the snowpack is in constant movement, even if we can't appreciate it with the naked eye. The wind can change direction and blow snow around to create dangerous accumulations where there was none before at a surprisingly quick rate and temperatures vary, affecting the stability of the snowpack.

In Scotland this is especially true because of the rapid influence of the Atlantic weather coming in from the West. Within hours you can go from a perfectly stable Scottish snowpack to a hair-triggered if-you-even-look-this-way-it-will-all-avalanche slope or cornice. And you don't even need to be on that slope! If it's above you, it could still get you. So whereas in summer we might move on from D pretty quick and carry on with the protocol R ABC, in winter, we must always be on our guard and consider ourselves in potential Danger almost continually. One way to do this is to keep re-assessing our position constantly.

Initial assessment:

So you manage to get down to your friend safely, say by front-pointing down the slope they've just slid down out of control. Whilst you're doing this, your heart is racing; try to keep calm and formulate a plan for when you get to them. Shout for Help! You never know, other people in the corrie might have seen you and your cries for help will spur them on to you. What about your friend? Are they shouting their heads off in pain? This is a good thing! It means they are aware and Responding (R) to pain, maybe even able to make coherent sentences, which means their Airway (A) is clear and they are Breathing (B), so we can tick these three off. So what else can be wrong with them? Most likely will be a lower limb injury.

Around 50% of fallen climbers/hill walkers sustain a lower limb injury as a primary injury. This is followed by a suspected spinal (15%) and head injury (10%). However, whereas it's unlikely that your friend will die of a broken leg (within reasonable time), they are more likely to die in the short term of severe bleeding. So we are thinking first to look for a severe bleed or Circulation (C) problem. Where's the hole where the blood's pouring out from? In winter we carry an incredible amount of sharp tools that can easily inflict a wound into our soft skin. Many fallen casualties are recovered with their own axes or crampons impaled into them.

If you think about this, it's not so surprising: you've attached yourself to your ice axe with a leash and as you fall you lose control of your axe which is now hurtling around your wrist randomly and at high speed. If it's a crampon point into a calf muscle, say, it's going to be a puncture wound, painful, but unlikely to be life-threatening. Any open wound should be dealt with the standard way of applying pressure and elevating to avoid further blood loss. If it's a pick of an axe that's gone in, it's much more serious.

Any embedded objects should remain embedded, as you might create more damage pulling the thing out; plus, it's acting as a plug. Leave it in, apply pressure around the wound, pad around it and support your friend so they can relax a bit. Use snow to build support in the most comfortable position you find them in. In general, casualties are very good at finding the least painful position for them; don't force them to move if you don't need to. Insulate them from the snow as a non-mobile casualty will be prone to hypothermia in no time (see 2. Hypothermia).

The situation develops:

When you arrived at your friend they were still talking and as you were helping them into a supported position and stopping the bleeding they mumbled about not feeling well and proceeded to vomit before slumping to the ground. Suspect a head injury. A head injury or a spinal injury should always be considered when the casualty has fallen down or bumped their way down a slope. You are now in a more serious situation as you have now gone back up the first aid protocol to Response. Any form of head injury that leads to loss of consciousness also leads to your friend not being able to maintain their Airway open.

Your priority now is to maintain their Airway open and make sure they are Breathing. You must put them into the Safe Airway Position or SAP. If help hasn't arrived yet from other hill walkers/climbers, this is the time to get on the phone and ring 999, ask for the Police and Mountain Rescue. The information they'll want to know is your location with at least 6-digit Grid Ref and descriptive (ie. East of the stream junction), who the casualty is, injuries to casualty, their Response level (anything less than completely 'with it' is considered Unconscious) and emergency equipment you have with you. If you can send them a picture of the view you have, the team is normally pretty good at pinpointing your location.

When it's all going wrong, this is where you'd rather be. Don't send the rescue team a photo of your latest Caribbean holiday.

Also, take a moment now whilst you are reading this in the comfort of your living room to register your mobile number with www.emergencysms, it's a free service originally set up for deaf, hard of hearing or people with speech impediments so they can text through to 999 in case of an emergency. This will be useful in areas with poor reception or text-only signal.

Once you're grounded, your priority is to stop yourself and the casualty from getting hypothermia. If you friend survives the first Golden Hour, there's hope that they'll make it through till the on-foot Mountain Rescue team arrive. Never assume that there will be a handy helicopter available, as civilian incidents are not a priority for the military. An organised rescue in winter can take anything from 2-3 hours to over 12 hours, depending on where you are and weather conditions. So hunker down and prepare to survive.

About Rocio Siemens

"As an MIC I work the winter season in the Scottish Highlands, over the summer I work in North Wales and across the UK providing climbing and mountaineering services, I am a member of AMI (Association of Mountaineering Instructors). I am also an International Mountain Leader (BAIML). I use this for trekking work in Europe and the Greater Ranges. In May 2009 I joined the British Mountain Guides training scheme and I am currently a BMG trainee guide. I'm a brand ambassador for Adidas Outdoor and DMM."

Ibex Mountain Guides is run by the husband and wife team, Owen Samuels and Rocio Siemens: www.ibexguides.com

Comments