Telling tales is something climbers and hill walkers excel in. How many of us have sat round a bothy fire or in the crag-side pub, glass in hand, and heard climbers tell tales of desperate moves on crumbling rock or walkers relating days lost in Highland blizzards? These are the stories that bind the outdoor community together, these are the legends of another world. We have all heard these stories and been inspired by their telling.

I was in a bothy, high in the Cairngorms, one winter's night. There were four of us huddled before the dying embers of the fire and, as they say in the Highlands, drink had been taken. I told a few of my more memorable stories and someone suggested I should write a book. The thought had never occurred to me before but that idea took root in my mind and its been fermenting away for a while. Now I've done something about it.

When I began writing the book it was really a farewell to the hills. I thought I had finished with all that and wanted to move on to other ways to get my adrenaline fix, like stand up comedy and performing in the theatre. That was the plan but writing changes you, and as I wrote the book the pull of the mountains returned and now I am as active as I always was.

The hard thing in writing the book was what to leave out. In forty years of hillwalking and climbing you tend to accumulate a lot of experiences, many of which make great stories. The book follows my early experiences of exploring the Lake District and walking the Pennine way in the 70s. In the 80s I moved to Scotland, took up winter climbing in a big way and joined a Mountain Rescue Team.

Alex Lowe said, "the best climber is the one having the most fun". If you measure success like that I'm a super star. I think we've forgotten how to enjoy ourselves, everything is so serious these days. I wanted to share the fun I've had in the mountains so there are a lot of laughs in the book as well.

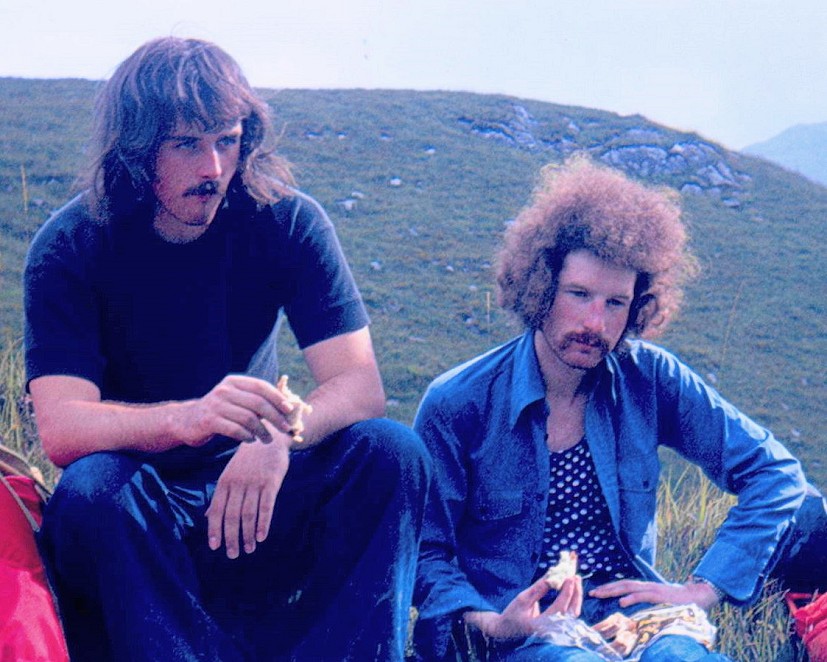

An Early Trip to the Mountains

The hill grows quickly steeper, the day hotter, the scree looser and more insubstantial with every step. In the ever increasing heat we take one step only slide back down to where we have started, as though on some kind of mountain treadmill. Soon we are all sweating and struggling under our sacks with each step. Phil, who is at that awkward stage that teenage boys grow through when the length of their limbs exceeds their ability to control them, quickly begins to lag behind. After a few hundred feet we are all tiring when poor Phil drops his rucksack and begins vomiting into the scree.

'What did you have to drink Phil?' I ask, thinking a surfeit of cider might be to blame.

'Just tea!'

'Oh, right.'

'Well... then I had some milk' he remembers, mid heave.

'Oh well that shouldnt...'

'Then, I think, there was another tea.'

'Well it is hot,' I suggest, trying to offer moral support in that typically English way of stating the bleeding obvious.

'Yes it is,' he burps, 'so I had some fizzy orange'.

'Ah', Dr Burns is beginning to form a diagnosis. 'Perhaps it was the fizzy orange'.

'But I dont think it was the orange.'

'No?'

'No, I think it might have been the strawberry milkshake I had after that', he totters unsteadily on his feet before his legs give way again and he collapses back onto the hillside with a grimace.

In Trouble on The Ben

I have climbed into a place where nothing works, the veneer of ice glazing the rock is too thin to allow me to drive my ice axes into yet too thick to allow me to climb the rock. Im high on the cliffs of Ben Nevis, Britain's highest mountain, its cold, its going dark and I struggle to contain the rising panic. Once again I turn towards the louring face, once more I summon all my determination. All my years of climbing experience tell me that the next few feet of rock are close to impossible for me to climb but there is no other way so that is the route I have to follow. I curse myself for my stupidity in getting me and my climbing partner, Joe, into this position. I think about my two girls, my wife and then take the only option there is, I keep moving. Hooking my ice tools over the top of the small overhang in front of me, I struggle for some kind of purchase with my feet, the snow is sugary and soft, offering the steel talons of my tools little security. Scouring the rock walls above me for a crack to take a piton or a nut, anything to give me some defence against plunging into the deadly abyss below, I find nothing but blank walls.

Oh God, this is desperate.

A YHA on the Pennine Way in the 70s

That night, in bed in the Youth Hostel, I close my eyes for what seems little more than a moment when I am dragged into instant wakefulness by trumpets and bassoons blasting out inches from my head. For a few seconds my stunned brain cant make sense of what is happening, then I realise the awful sound that has woken me is The Ride of the Valkyries issuing forth at ninety decibels from a speaker above my bed.

'Jesus Christ!' I cry out, realising that the whole night has passed and it is morning.

As I cower beneath the sheets, the door bursts open and a pair of bosoms charge into the room closely followed by their owner, the Warden. She tears open the curtains and light floods into the room.

'Time to get up!'

With that she and her bosoms are gone, leaving everyone in the room trembling in the aftermath of a Wagnerian nightmare. God knows what would have happened if she had entered the room and found some poor soul enjoying a secret cigarette by the open window. He would have been nailed to the wall of the hostel as a hideous blood eagle warning with, of course, a sign beneath his mangled corpse: NO SMOKING MEANS NO SMOKING.

Running Out of Food on a trek across Knoydart

All we have is the three biscuits I am carrying, we have had to walk an extra day and our supplies have run out. Once our sleeping bags are out we settle down for our feast. I fumble in my rucksack and pull out two of the biscuits. I spend a minute or two searching the pockets for the third but come up empty handed.

'I can't find the other one,' I explain. This gets Martin and Joes full attention. When all you have is a handful of biscuits their whereabouts assume immense importance. I tip out my rucksack, spare socks, toothbrush and an assortment of clothes land on the grass, but no third biscuit.

'Well it's got to be somewhere,' Joe exclaims. Frenzied searching ensues. Sleeping bags are shaken out, each rucksack is minutely but the whereabouts of the biscuit remains a mystery. 'You sure you dont know where that biscuit went?' Joe is suspicious.

No, of course not, Im stung by the inference that I might have secretly scoffed it.

'Well there were three,' Martin interjects.

'I know that. It must have... got lost.' As I say these words I realise that they sound like the pathetic pleading of a guilty man. Martin and Joe look at me with silent accusations in their eyes. Suspicion clouds the air. That night we each dine on two thirds of a biscuit. We are three men miles from anywhere, in some of the most magnificent scenery in the world, and the one thought that obsesses all of us is the fate of a Jacobs Club biscuit.

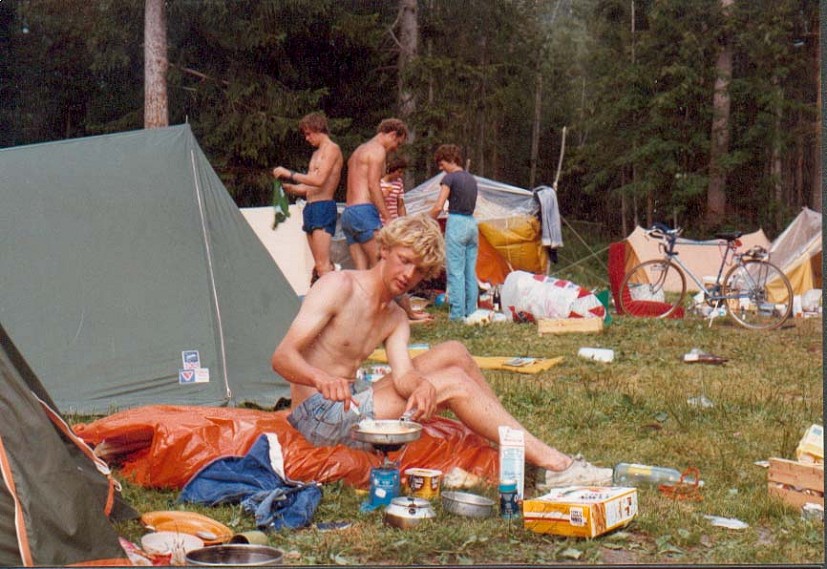

Snell's Field Chamonix

It's late morning in the little campsite at the foot of Mont Blanc. Hung over climbers emerge from their tents, scratching in the chill at the start of the day. The air is full of languid chatter and the roar of primus stoves and the campsite is a sordid jumble of tents and improvised plastic shelters. Last nights campfires send wisps of smoke curling in to the still air as they smoulder and die and ropes, carabineers, boots and ice axes litter the floor. The sun has not reached the camp site yet. The giant mountain looms over the little community of climbers and casts a long shadow across the valley of Chamonix far below its stark, ice white summit.

I'm squatting over my small pan, gently poking a tea bag around in the hot water. As I watch the liquid in the pan slowly turn brown, a police car pulls up on the small dirt road. It's one of those fragile 2 CVs that look as though they are made of egg boxes and corrugated cardboard. A tall, young police officer steps out, placing his pill box hat carefully on his head. With meticulous care he straitens his cap, incongruously smart amongst the scruffy chaos of the climber's camp. Slowly he walks across the field cluttered with tents, stopping here and there to question one of the bleary eyed tent dwellers. His footsteps are measured, gaze steady, expression sombre as he moves methodically from one tent to another. He is looking for someone.

As he passes the bleary eyed climbers stillness follows him; gradually the whole place falls silent and every eye turns to watch the tall blue figures deliberate progress. He stops at one tent, the occupant stands, nods and then points. The Gendarme follows his gaze to where a young girl waits. She is in her early twenties, in blue jeans and a scruffy pullover, her blond hair, an unkempt mass, hides her face. I notice she is trembling as the policeman walks towards her and looks like she might turn and run. Instead she waits, motionless. He comes close to her and whispers a question, she nods. The Gendarme talks to her quietly for moment, then the girls knees buckle and she is falling. The young police officer has been expecting this; he catches her shoulders gently in his arms and steadies her. Together they walk slowly towards his car. The Gendarme, erect and smart in his blue uniform, the girl, scruffy in her jeans and wild hair, sobbing quietly. I watch, mute with horror, as they drive away down the dusty road in the policemans rattling car. Once the car passes from sight the camp becomes alive with rumours of rock fall, avalanche and tragedy.

It's only than that I realise who he is, that tall young man in the blue uniform. He is the angel of death.

John Burns is currently looking for a publisher for his book The Last Hill Walker.

"I've got to know my readers through my blog and that's been really interesting" he says. "It's great to know what people like and don't like. I think that has really strengthened my writing."

"My time in the hills has been and still is a riot. If I can share even a little part of the enjoyment, laughter and inspiration I've found in these mountains, I'll be happy with my work."

- For more see from John see his blog

- OPINION: It's The End of An Era For Cairngorm Bothies - And The Start of a New One 22 Oct, 2023

- OPINION: The Hot Tent - the opposite of fast, light, and miserable 2 Nov, 2022

- PODCAST: Lyme Disease - What You Need to Know 12 May, 2022

- Desert Island Peaks: John Burns 14 Jan, 2021

- 10 Tips For a Winter Bothy Night 20 Dec, 2019

- Eight Things They Never Told You About Mountain Navigation 2 Aug, 2018

- OPINION: Are Bothies Being Commercialised to Death? 19 Mar, 2018

- Ten Things They Never Told You About Hillwalking 16 Nov, 2017

- 40 Years On The Pennine Way 21 Sep, 2017

- GEAR NEWS: The Last Hillwalker, by John Burns 22 Aug, 2017

Comments