Navigation in Poor Visibility: The Essentials

Over the next few months UKHillwalking will feature a series of articles on key hillwalking skills, in association with Mountain Training, the provider of nationally-recognised leadership qualifications and skills courses in walking, climbing and mountaineering. Mountain Training's awards and courses are run by approved providers, based all over the UK and Ireland. We've asked several of them to write us each an article for the series.

Here's Graham Uney of Wild Walks Wales, on how to keep your bearings in poor visibility. These tricks are useful at any time of year, but perhaps more so in the long dark nights and poor weather of winter.

L

ast week, right at the start of the winter season, I sat in a group shelter at the summit of Arenig Fach in Snowdonia. Outside the clouds were blowing in, rain had started to fall, and the good visibility we had enjoyed on our ascent of the mountain was now reduced to about 15 metres. Inside the group shelter with me were five candidates on a Mountain Skills course. Four of them had never had to navigate in bad visibility before, and so we took the time to get everyone prepared for what would be an interesting descent.

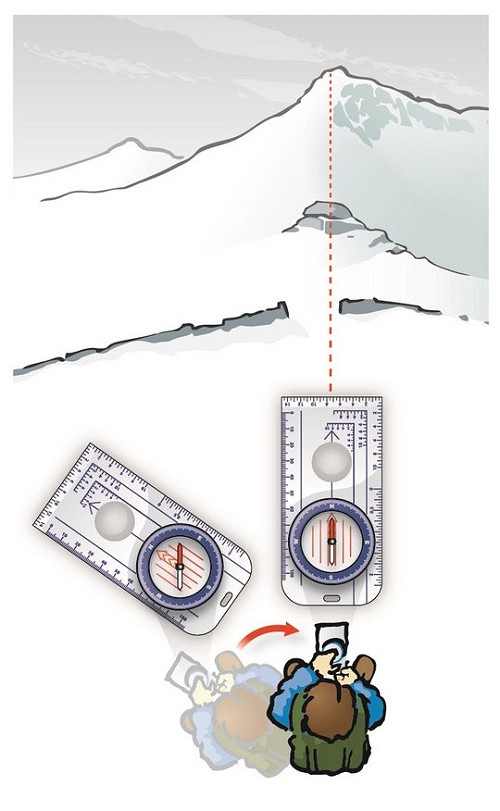

We had spent part of the day looking at how to take a compass bearing from the map. This technique uses the compass like a protractor, and enables you to measure the angle between the direction you want to travel in, and the north on the map. Once the bearing has been taken, you can then follow the compass along that direction and, all things being well, you should hit the point you were aiming at.

"In the winter with daylight so short there's every chance you'll be descending at night, in poor visibility. There is no reason to worry about this with the right navigaiton techniques in your toolbox"

We'd done this half a dozen times or so during the day, so everyone had the gist of what we were now doing huddled in our shelter. Then someone asked the inevitable question. 'How are we going to follow a bearing in this mist?' So far, it had been a simple matter of lining up the two 'norths' on the compass (the one on the needle that spins around, and the one on the dial) then looking to see what direction the arrow on the base-plate of the compass pointed in. Looking along that direction arrow, we'd talked earlier about picking an obvious point along the line of the arrow – say a boulder, prominent clump of heather, or whatever, then walking to that point and repeating the process. The whole thing is aimed at walking in a dead straight line between where you started, and where you want to end up, and it had all gone really well. So far. But now, with visibility being so reduced, it was clear that picking an obvious target in the swirling cloud would not be so easy.

Once you have taken a bearing, rotate the entire compass to align the north (red) end of the needle and the orienting arrow. Keeping both needle and arrow aligned, follow the direction of travel arrow

So, what can you do about this? You can often get by with just looking for something that is much closer to walk to on your bearing, but sometimes, say in the middle of an open moorland or featureless mountain top, this becomes very difficult.

Playing leapfrog

On Arenig Fach I introduced the idea of using a person as the marker to walk to. We started out by sending one person forward to the limit of visibility – they walked roughly on the bearing, then stopped and turned around to face the group. One person in the group then gave them a hand signal to step left or right while checking the bearing, putting their hand up in the air when the forward marker person was on the bearing. The marker then stayed put while the rest of the group caught up, and the whole process was repeated. Once it was clear that everyone in the group understood what we were doing, we were able to modify this technique by having a couple of people go forward, then as soon as the marker was on the bearing they would stay put while the second person walked the next section, all the while with the rest of the group catching up. With this leapfrog method we soon lost height from the summit, and dropped below the cloud base with the exact view we were expecting to see dead ahead.

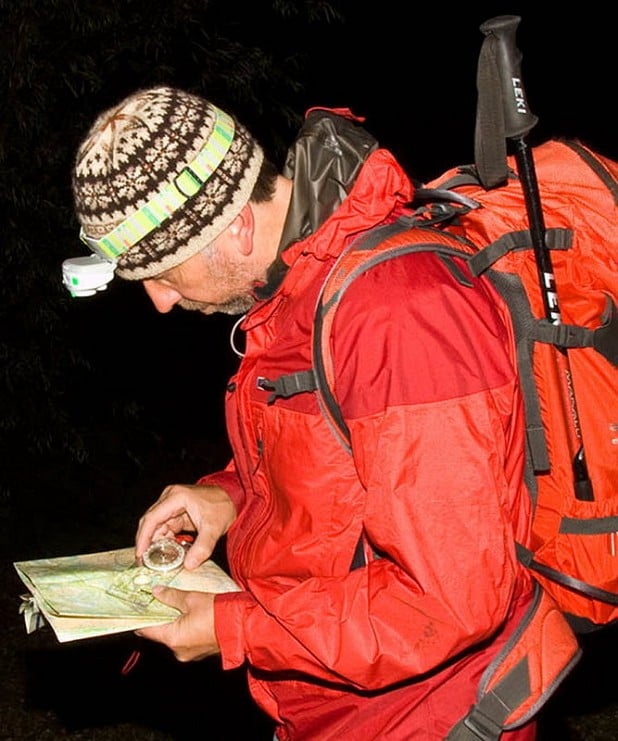

This scenario on Arenig Fach is actually the extreme example of what to do in poor visibility. But think about other times during your walk when you could potentially have reduced visibility. The obvious instance that springs to mind is night time. Especially as we are now well into the winter months, and the daylight hours are so short, there is every chance that at some point during your hillwalks you will be descending at night. And there is no reason to worry about this if you have the right equipment with you, and the right navigation techniques in your toolbox.

Another example of when you might need to navigate in a poor visibility situation is when walking through dense forestry plantations. Even in broad daylight you often can't see more than 10 – 20 metres where the trees are planted very close together. Now you could argue that there will be plenty of trees for you to sight on as a marker when following a bearing through this kind of terrain, and that is very true, but in practice it is oh so easy to forget which tree you are walking to on your bearing – they do all look very alike in the middle of a forest! So, use a person instead.

This all assumes that you know how to take a bearing, and how to follow it on the ground of course. There are some very good instructional books available, but I would strongly recommended that you learn navigation with an instructor in the outdoors. This is the only sure-fire way to know that you are learning the technques properly, and a good instructor will teach you progressively, and will introduce you to skills and techniques as and when you are ready to learn them. Also, navigation is a practical outdoor skill, and it is much easier to learn it outdoors, rather than at home with a book!

Orienting the map

Quite often we may find that the navigation required in poor visibility isn't as complex as taking and following a bearing. You may be walking along a linear feature – say a path, a stream, or perhaps a stone wall. You come to a junction, and as the mist has started to engulf you, you've become a bit confused and you're not sure which way to turn. If you have the ability to turn your map around so that all the features on your map are aligned with those same features on the ground, this will help you decide which direction to walk in. With practice many people can do this just by looking at the features and turning the map so that they match up, but a quicker, much more accurate way of achieving the same thing is to use your compass to help. Put your compass on your map to start. With this technique you can completely ignore the base-plate and the dial on your compass – it's the needle that swings to north that's the important bit. Because that needle points to north, if we know whereabouts north is on our map – and on all Ordnance Survey and Harvey Maps (these are the ones most commonly used in the UK) north is at the top of the map – simply turn the map around so that the compass needle points to the top of the map and you will have your map set. This technique is called either setting or orientating the map. Once you've got your map set all the features on the map will be lined up and in the correct position for those same features on the ground.

"The people who get seriously lost are those who walk along with the map buried somewhere in their rucksack"

Keeping tabs

I have a bit of advice that I always give to people on my courses, and I always explain that I know it sounds a bit flippant, but it is probably the very best advice you can ever take from someone with regard to navigation. This snippet of wisdom is – always know where you are on the map. Yes, yes, I know it sounds like I'm just trying to be clever, but what I mean by this is you should always have your map and compass handy. If you carry them in your jacket or trouser pocket then you can always pull them out whenever you come to a feature on the ground – be it a footpath junction, a stream crossing, a building, an obvious contour feature, or whatever – then set the map and work out where you are and the direction in which you want to travel.

There may be instances where you'll have to stop for a few minutes to work out your position, but by checking the map regularly if it all does go a bit pear shaped you can easily backtrack to your last known point and have another go.

The people who get seriously lost are those who walk along with the map buried somewhere in their rucksack, and who only produce it when the path they have been following disappears on a mountain plateau or in a wood. Trying to work out where you are on a map when you haven't really got a clue about your general location is very, very difficult indeed, and you will make lots of wrong decisions before you work it out. If you are able to work it out at all. In that scenario the best you can hope for is to turn around and walk back out the same way you've come, and your day's walking in the hills will have been wasted.

About Graham Uney

Graham Uney is the author of several walking guidebooks, and owns the walking company Wild Walks Wales. He has twenty years experience of running skills courses all over the UK for hill and mountain walkers, and is a course provider of the Hill and Mountain Skills Scheme, the Lowland Leader Award and the Expedition Skills Module for Mountain Training. He also offers the full range of National Navigation Award Scheme courses, and runs guided walks and rock climbing taster days too. For more info see his website.

Nb. for the 2014-15 winter season Graham is also a new Fell Top Assessor for the Lake District National Park - a role that will see him climbing Helvellyn every day to take weather readings and to assess the snowpack (see UKH news here).

About Mountain Training

Mountain Training's aim is to promote awareness of mountain safety through leadership qualifications and skills courses in walking, climbing and mountaineering. There are 11 qualifications which prepare people to lead walking groups on different types of terrain, supervise and coach climbing or instruct others in summer or winter mountaineering. All of the qualifications are administered by Mountain Training and delivered by approved providers. For more info see their website.