John Burns suffers the bothy-goer's worst nightmare, a fellow occupant who just won't shut up - even when asleep.

The moment I walked into the bothy I could tell something was wrong, I could feel the tension in the atmosphere. The last hour or so of the walk into Shenavall had become increasingly dismal as I'd followed the track down into the glen and past the old ruined cottage towards where the bothy nestles at the foot of the hill. What had started as mist had changed by degrees from fog to drizzle and then into a fine saturating rain. It had become what my mother would have called a wetting rain, that fine mist that laughs at Gortex and will eventually find your skin no matter how well clad. By the last half mile of the walk in, it was beginning to ooze through my gaiters and to seep up the sleeves of my cagoule. I was beginning to moisten at the edges, and not in a good way.

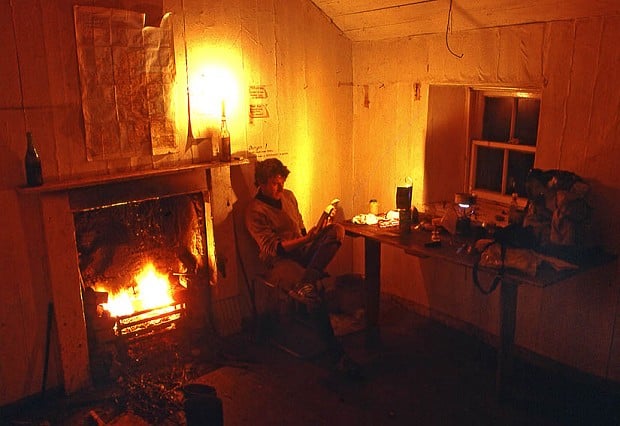

So it was with relief, that early autumn evening, that I sighted the bothy, noting the faint welcoming glow of a candle at the window and the wisps of smoke issuing from the chimney that hinted at the warmth within. I quickened my pace, anticipating an evening filled with laughter swapping tales with the occupants, sitting by the fire with steaming mugs of tea and a dram or two. It was with this image in my head that I pushed open the door and shook the rain from my clothes in the small porch. Entering the bothy I was instantly aware of a stony silence.

'He talked in long rambling sentences that made little or no sense. Words poured from his mouth like the rain issuing from the hut's gutters'

As my eyes became accustomed to the gloom I discerned three figures. Two older men were in a conspiratorial huddle on the far side of the room, hunched backs to the door. They turned to see who had violated their sanctum, the whites of their eyes registering a suspicion that bordered on hostility, or possibly even fear. In the centre of the room a large young man sat, a mop of tousled red hair framing his wide browed face. He at least was pleased to see me and welcomed me enthusiastically into the small wood-lined room that reeked, as all bothies do, of wood smoke, three day old socks and decaying food. He introduced himself; my mind has long since deleted his name, so let's call him Hector. He even pulled a chair up for me and offered me tea, a kind gesture I thought. The other two men beside the fire huddled even closer as Hector offered his hospitality, shooting me furtive, menacing glances.

There was no mistaking the vehemence of the odd looks the two men gave me. As I took my first sip of Hector's tea I wondered if these anti-social creatures treated all newcomers this way, or if I'd just stumbled in after there had been some disagreement - the best way to drink whisky, or whether Ben Nevis would make an excellent site for a wind farm. The horror of what happened next revealed all. I soon realised that they had been trying to warn me.

'After a while I began to wish him dead. I started to fantasise about how I would kill him, even to plan the act'

Hector began to talk. Looking back I have little recollection of anything he said, perhaps my mind has blotted that out, but talk he did. He talked in long rambling sentences that made little or no sense. Words poured from his mouth like the rain issuing from the hut's gutters. His words became a downpour, paragraphs deluged me, his mouth gushed gibberish out into the night air as he filled the bothy waist deep with a huge volume of verbiage. Soon I was drowning in Hector's verbal output. He talked without cease, it seemed without end. By some mystical process he never drew breath but went on and on and on into the evening.

After a while I began to wish he was dead. I started to fantasise about how I would kill him, even to plan the act. Smothering became my favoured option as I imagined his muffled words slowly ceasing as I forced my sleeping bag into his mouth. I looked over at my other two companions who were muttering to each other in the corner. One of them looked up and, making eye contact, we exchanged a look of deep, desperate despair. In that moment I knew that if I killed Hector, perhaps felled him with a blow from the cast iron frying pan that hung above the fire, dragged him outside and buried him beneath the nettles, it would be a secret that I and my fellow Hector sufferers would carry to our graves. We would pass the rest of the evening in quiet, gentle conversation, knowing that there would be no need to even mention Hector's departure from this mortal realm. All of us understanding that his removal, like disposing of a sheep tick in the groin, had simply been necessary.

Eventually, long after I had begun to wish I too was dead, we agreed it was bed time. I think it was 8:30. I settled into my sleeping bag content in the knowledge that now, at last, sleep would carry Hector off into the land of dreams and that finally he would stop talking. I was right. Soon he fell silent but for the sound of his gentle snores. At least that's what happened at first, but then, returning with all the joy of an unpaid tax bill, Hector's voice began again its monotonous drone. I realised with mounting terror that he could even talk in his sleep. Robbed of the influence of his conscious mind Hector's diatribe made as little sense as it had when he was awake. Clearly the connection between his brain and his mouth was tenuous.

The following morning we all went our separate ways and I tried to push the lamentable evening to the back of my mind as I plodded back to my car over the hills. Driving home to Inverness I spotted a walker hitching by the side of the road. Without thinking I stopped and the hiker climbed into the passenger seat. To my horror I realised too late that it was Hector. I hadn't recognised him with his mouth closed. He explained that he was about to miss his train home from Inverness. He'd have nowhere to stay in Inverness if that happened, and wondered if I might put him up for the night.

'Oh don't worry' I told him quietly, 'I'm sure we'll get you to the station in time.'

I am not by nature a fast driver but on that occasion I pressed the accelerator to the floor and kept it there for the whole journey. I drove as though pursued by the devil, as though chased by every midge in the Highlands; I drove as though I was trying to catch last orders for the end of time. Hector sat in the passenger seat, his white knuckled fingers driven deep into the chair upholstery, feet braced against the dashboard. He sat with eyes fixed on the road ahead, staring through the windscreen as though he could see Death driving a Forestry Commission lorry straight at us round every bend.

But, more importantly than all of that, he sat in total and complete silence.

For more tales from John Burns see his blog.

- OPINION: It's The End of An Era For Cairngorm Bothies - And The Start of a New One 22 Oct, 2023

- OPINION: The Hot Tent - the opposite of fast, light, and miserable 2 Nov, 2022

- PODCAST: Lyme Disease - What You Need to Know 12 May, 2022

- Desert Island Peaks: John Burns 14 Jan, 2021

- 10 Tips For a Winter Bothy Night 20 Dec, 2019

- Eight Things They Never Told You About Mountain Navigation 2 Aug, 2018

- OPINION: Are Bothies Being Commercialised to Death? 19 Mar, 2018

- Ten Things They Never Told You About Hillwalking 16 Nov, 2017

- 40 Years On The Pennine Way 21 Sep, 2017

- GEAR NEWS: The Last Hillwalker, by John Burns 22 Aug, 2017

Comments