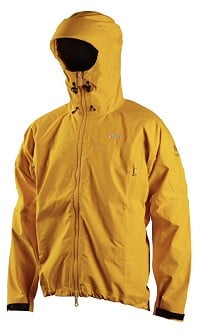

Goretex Active Shell, Polartec NeoShell, Mountain Hardwear's DryQ Elite, Nikwax Analogy, eVent, Paclite, Pertex Shield, wired hoods, waterproof zips, drawcords, stretch panels, pit zips, hydrostatic head... The lexicon of breathable waterproof jackets is enough to baffle even the kinkiest gear fetishist. These days there's just so much on offer; so what to look for when buying a jacket, or 'hard shell' as they're sometimes called? Dan Bailey takes a brief stroll through some of the basics.

How do you buy a waterproof jacket? Maybe you think this is a bit of a non-question. Surely it's as simple as entering a shop and grabbing the first breathable waterproof jacket in your favourite colour? Well you could do that, sure; but before opening your wallet might I humbly suggest a brief pause for thought? Don't let anyone give you the hard sell on that hard shell. No decent waterproof could be called cheap, so it really pays to consider what exactly you'll be wanting from yours, where you'll mostly be using it, which materials, attributes and add-ons you really need and which might be extraneous. There's more to any waterproof jacket than meets the untrained eye, with enough diversity in proprietary fabrics, styles of cut and features to fill several articles. We've only got the one, so I'll keep it simple.

Fabrics

There is a bewildering number of waterproof breathable fabrics out there, with an already busy market having been further complicated this year by the launch of Goretex Active Shell, Polartec NeoShell and Mountain Hardwear's DryQ Elite. It's like buses – you wait years for a new development in membranes and then three come along at once. Big claims are made about the breathability of all three fabrics, though for now the jury is still out. Longer-established membranes such as eVent and Goretex Pro Shell generally perform pretty well, the advantage if you're buying now being that you may not be paying such a premium for novelty compared to the very latest fabrics. Or perhaps you want to go a little left field with something like Nikwax Analogy (as used by Paramo), or Keela's System Dual Protection, both of which work on a multi-layer principle? Converts say these are among the most waterproof, breathable and long-lived fabrics available, though there are drawbacks in terms of the extra weight and warmth of garments that use this multi-layer system.

What does 'waterproof and breathable' actually mean?

A garment that was waterproof in both directions would be next to useless because while keeping the rain out, it would also hold your sweat in. An adult working hard can excrete up to 1l of sweat per hour, so the layers underneath would soon be saturated and either you would boil in the bag or end up chilly and miserable (usually both). In the cold old days outdoor types had to be masochists; I shiver at the memory of 1980s school field trips in those clammy council-issue cagoules. Perhaps there's a correlation between the invention of Goretex and its ilk, and the emergence of hillwalking as a mainstream pursuit? Well, it's a theory.

Of course modern jackets don't literally breathe, but thanks to materials developed in labs they do manage a clever trick, holding rain at bay (after a fashion) while letting sweat out (more or less). There are a number of ways to achieve this, the best known being the membrane principle used by Goretex and others. Droplets of liquid water (ie raindrops) are far larger than the molecules of water vapour produced by your body, so if the holes in the membrane are small enough it effectively acts as a unidirectional barrier, with the moisture allowed to permeate from inside but not penetrate from outside. A difference in humidity between inside and outside the jacket drives this venting process, the humidity generated when you start working up a sweat. The latest generation fabrics - Polartec NeoShell, Goretex Active Shell and Mountain Hardwear DryQ Elite - owe their improved performance to increased air permeability, meaning that you don't have to be sweating for as long before they start to work. But even the best fabrics have their limits, and these will be most apparent when working hard in warm wet conditions. With that in mind there can't be many places better for testing waterproofs than the soggy, muggy British hills. Oh joy.

The delicate membrane will generally be wedded with a tougher face fabric, the bit of the jacket you actually see and the part that most affects a garment's weight and durability. This is treated with a DWR (Durable Water Repellent) finish since a 'wetted out' face fabric would impede the performance of the membrane. To maintain the performance of a jacket over time this DWR needs to be periodically refreshed by washing and re-proofing.

Cut to fit

We all come in different shapes and sizes, and so do jackets. It's a bit of a gamble to buy a jacket online without actually trying it on. Are the shoulders as broad as yours? Is there beer belly room? Are the arms long enough and the cut 'articulated' enough to let you freely raise your hands over your head – for climbing say, or waving for help – without the jacket impeding your movement or riding up at the back? For some time climbers' fashion has favoured a short-cut body, ostensibly to allow unhindered access to a harness, while more walker-oriented jackets are traditionally supposed to be longer in the hem because that keeps more of you dry (some important bits actually). However it's not always that clear cut since some climbing jackets are fairly long, while there are plenty of walking shells that come down no lower than the waist. Personally I prefer something reasonably (not restrictively) long even for climbing, since I find a longer jacket stays tucked under your harness better and offers more protection from the elements. Many jackets incorporate stretchy panels to aid freedom of movement (thus using a minimum of material in order to trim excess weight). Much the same effect can be obtained with thoughtful tailoring too.

Lined or unlined?

Some top-end waterproofs used to sport a mesh lining. I guess this was to hold the outer fabric away from the skin to reduce the feeling of clamminess, but the main effect (yes I am old enough to remember) was simply an increase in weight and bulk. Modern shells are so breathable that in general a lining would be redundant (the exception that springs to mind being Paramo jackets).

Main zip

Would you prefer a full length zip, or an over-the-head half-zip smock style shell? A conventional full-zip jacket is more versatile, easier to put on and easier to vent; against this the less popular smock style is lighter for an equivalent jacket, and has less length of zip to leak. And all zips do that. Water resistant zips are becoming more or less standard these days, but even some manufacturers will admit that in prolonged driving rain they'll let a little rain in - and that's certainly my experience. To counter this any waterproof jacket worth owning will have an internal flap along the length of the zip, to channel away water that does penetrate. The current trend is to expose the zips as an eye catching part of a jacket's 'colourway' but to my mind this is a triumph of fashion over function. A good old fashioned external 'storm flap' might look a bit daggy but it will improve the weather proofing of any zip.

Pit zips?

Even as fabrics become more breathable some manufacturers have stuck with the pit zip, a self-explanatory feature designed to maximise a jacket's venting options with only a comparatively small penalty in added weight. Having worn jackets both with and without I'm a little ambivalent. Yes it can be nice to air the armpits when you're toiling uphill, but then undoing the jacket's main zip does a pretty similar job. It would have to be an uncommonly well disciplined and vertical variety of rain that would enter via the main zip but not through the armpit holes. Still, bar the tiny extra weight they don't actively do much harm; except provide one more point at which the jacket might leak.

Hood

Many waterproofs, particularly budget models, are let down by their hood. It's a pretty fundamental feature if you think about it, being effectively a big hole at the top of the jacket through which driving rain really wants to enter. With the aid of a drawcord it's got to form a near-weathertight seal around the face, ideally covering the chin to protect as much of your face as possible from cold wind and flaying hail. In order not to restrict visibility a well designed hood has to move with you as you turn your head. If you intend to scramble or climb as well as walking in your jacket then look for one with a hood cut generously enough to accommodate a helmet; there should also be a drawcord at the back so the hood can be tightened to fit when going helmet-less. The soft flappy peaks found on the hoods of even some top-dollar jackets are not ideal in a gale, when you're better off with the protection of an old fashioned wired peak that can be shaped to keep the wind (and hood) out of your eyes.

Cuffs and hems

The cuffs are another point at which, over a long wet day, some water will inevitably enter. Some featherlight models have simple elasticated cuffs, but on most jackets an adjust-to-fit velcro tab is standard; I doubt there's much to chose between any of them. A drawcorded hem with adjustment toggles is also a near-ubiquitous feature; toggles at the front might get tangled with a belay plate, so climbers and scramblers should go for a jacket that adjusts on the side. The elasticated hems found on some superlight jackets are not adjustable and generally don't offer as good a fit.

Pockets

In order to save precious grams stripped-down lightweight jackets are unlikely to feature more than two pockets - indeed a single pocket is not unknown. In a general purpose or mountain jacket however, three or four seems a good number as between hat, gloves, compass and snacks you usually need quick access to quite a few items. Unless you are totally focused on saving weight at the expense of function then at least one pocket cut big enough to hold a folded OS-sized map is pretty much essential. Inside pockets aren't an awful lot of use in the rain. Pockets should be accessed from the outside, and located high enough not to interfere with a rucksack hip belt (or climbing harness if you're that way inclined). Pockets are obviously another potential point of water ingress, and as with a jacket's main zip, 'waterproof' zips are best backed up with storm flaps - though they often aren't. If the pocket linings are mesh rather than solid fabric they can act as a vent to help avoid overheating; the downside to this though is that a mesh lining won't stop any water that manages to penetrate the zip.

Value for money

What's the difference between a £150 jacket and one costing three times that? Is a garment's performance reflected in its price tag? Yes, but only to an extent. Top-of-the-range jackets should be distinguished by more than just branding and fashion. As a rule, shelling out more ought to guarantee a jacket with one of the most breathable membranes, face fabrics that best balance durability and lightness, an ergonomic cut, especially well thought-out features and the best quality construction. But if your budget won't stretch, then no big deal. Some mid range jackets also boast any or all of the above, or as near as dammit, while even a sub-£100 waterproof from a high street brand is likely to out-perform the sort of clobber they wore up Everest in the 70s. Beyond a certain threshold the law of diminishing returns inevitably kicks in, with rising cost yielding increasingly incremental gains in performance. Though there are obvious differences a Skoda will get you to work just as surely as a Jag; likewise if you can't afford an Arc'teryx, then a Craghoppers jacket will do. Only you can decide if you're worth the very best, or whether adequate is good enough.

Fit for purpose?

Perhaps you're out every week winning mountain marathons; or you could be more a climber, and only ever deign to walk up hills when the crags are out of condition; or maybe you're new to all this, and daunted by the thought of Striding Edge. Hillwalking is a broad church, and just as there is no one-size-fits-all definition of its parishioners, so no single waterproof is ideal for every purpose. What's yours going to be for? Yes you can scramble, backpack and dog walk in the same old jacket, but I'd venture there are enough differences in designs and features to group waterproofs according to the uses to which they are best adapted. Here are three broad categories – there's bound to be some overlap:

Lightweight jackets

Are you a light-and-fast (or even light-ish-yet-still-slow) aficionado for whom every gram counts? If so there are some impressively wafty waterproofs available nowadays, with the skinniest models weighing in at under 200g. While these can be as breathable and waterproof as the next jacket, their thinner face fabrics are unlikely to be as durable and long-lived as more conventional models, and in order to save weight manufacturers will generally compromise on features such as quality hoods, number of pockets and so on. Featherweight jackets are rarely cut as roomy, making it harder to layer up in cold conditions. Save these for summer walks, fair weather overseas trips and weight-conscious competitive events.

All purpose, all-season jackets

You could also call this the standard walker's category, though by this I don't mean to imply anything derogatory about the performance of such jackets – which will be up there with the best. You'd be equally happily packing this for a summer hut-to-hut holiday in Norway or a winter battle up Braeriach. These shells are likely to be fairly long in the hem, and roomy enough to accommodate several layers underneath for winter walking. They'll probably sport plenty of pockets for hands, gloves and hats – and any walking jacket worth its salt will have at least one easily accessible pocket large enough to hold a folded OS map. Hoods should be well fitting and move with the head, and a wired peak is always welcome; but the hood may not be cut large enough to accommodate a climbing helmet (and you may not want it to). With the generous cut and number of features these won't be the lightest jackets available, but thanks to modern materials and construction the latest designs still weigh much less than jackets of yore and there's no need to buy a brick.

Mountain jackets

If you're intending to do lots of scrambling, year-round climbing or winter walking at the mountaineering end of the spectrum then it might be worth investing in something designed with these purposes in mind. They'll do fine for less hardcore hillwalking too of course. These jackets need to be roomy enough to accommodate several layers underneath, while sleeves should be cut to offer the best possible range of arm movement. Perhaps there'll be underarm stretch panels to help in this regard. The type of membrane used may be the same as on more general purpose jackets, but the face fabric should be tougher to better resist abrasion when climbing, particularly in high wear areas. It's vital that the hood is helmet-compatible and generally well designed. As I've said, short hems are the fashion in mountain jackets, but they're not to everyone's taste and some models do offer a little more length in the body. Perhaps these won't be the lightest jackets available, but they should provide bomb-proof performance for many years.

Limitations

Waterproofs aren't magic of course. Even the last word in hard shells is going to let in some moisture if you stand under a waterfall, and build up a little dampness inside if you go running in a heatwave. Besides, a jacket can only perform well if you help it do its job. A clean jacket will work better than one whose membrane's pores are clogged with grease and dirt, while a judicious bit of reproofing may work wonders on the DWR of a knackered garment. More fundamental still, you'll only feel the full benefit of all that breathability if the layers you're wearing underneath can wick away moisture. There's little point splashing out on a £300 shell if you're going to pair it up with a cotton T-shirt. Layering is a big subject in itself, so we'll cover that in a future article.

- INTERVIEW: Exmoor Coast Traverse - England's Best Kept Mountaineering Secret 10 Apr

- REVIEW: Rab Muon 50L Pack 9 Apr

- REVIEW: Boreal Saurus 2.0 22 Mar

- REVIEW: The Cairngorms & North-East Scotland 1 Mar

- REVIEW: Mountain Equipment Switch Pro Hooded Jacket and Switch Trousers 19 Feb

- Classic Winter - East Ridge of Beinn a' Chaorainn 12 Feb

- REVIEW: Salewa Ortles Ascent Mid GTX Boots 18 Jan

- REVIEW: Patagonia Super Free Alpine Jacket 7 Jan

- REVIEW: Deuter Fox - A Proper Trekking Pack For Kids 27 Dec, 2023

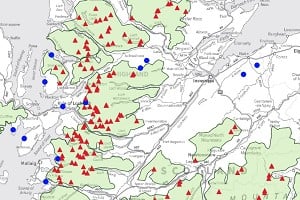

- My Favourite Map: Lochs, Rocks, and a Bad Bog 27 Nov, 2023

Comments